Appleby History > Alan Roberts > Scandalous Neighbours

Scandalous Neighbours

The Royalist Clergy of the Southwest during the Great Rebellion

by Alan Roberts

The Civil War years were an unsettling time for the clergy in the parishes around Appleby. At the start of the war Leicester was in the hands of the parliamentarians who governed the county through the County Committee. Parsons suspected of having royalist sympathies, those abiding by the old Anglican religion with its Prayer Book, rituals and ceremonies, faced ‘sequestration’, a process of being ejected from their livings and replaced with ‘intruder ministers’. Ejected incumbents in this southwest corner of the county were commonly accused of ‘observing ceremonies’, neglecting their parishioners, drunkenness, frequenting alehouses, and in some cases visiting the king’s garrisons, despite this being a ‘capital’ offence. A few were charged with being ‘malignants’, actively supporting the king’s forces.

The most troublesome royalist garrison in this part of the county, the ‘thorn’ in the side of Parliament, was Hastings’ stronghold at Ashby-de-la-Zouch, described in parliamentary newsletters as a nest of royalist sympathisers. According to one highly partisan report, the Perfect Diurnal of November 14th, 1644, ‘there are as debased wicked wretches there as if they had been raked out of hell’. Parliamentary propaganda portrayed the Ashby garrison as a refuge for thieving rogues and renegade clergymen, men who ‘cozen and cheat one another, steal one another’s horses and ride out and sell them’. The Perfect Diurnal records that the soldiers had even developed their own devilish style of greeting one another, ‘if they affirm or deny a thing it is usual to do it with the saying, “the devil suck my soul through a tobacco pipe” … no wonder, they have three malignant priests there such as will drink and roar, and domineer and swear as well as ever a Cabb of them all’. (Nichols, p. 39) Judging from the number of parsons charged with visiting the town or captured there, Ashby was a popular meeting place for the royalist clergy from surrounding parishes in the mid 1640s.

The bulk of information relating to sequestration and charges of malignancy is recorded in John Walker’s, Sufferings of the Clergy, which was firstpublished in 1714 and later revised by A.G. Mathews. Walker records that Abraham Mould, the rector of Appleby was ejected from his living and replaced by the intruder Jonathan Clay in 1656 (a comparatively late date). Not much is known about the exact reasons for this ejection except that Mr Mould was ‘put to great expense attending Committees’. His sequestration does not necessarily brand him as a royalist. However the fate of some of the local clergymen from neighbouring parishes within walking distance of Appleby is instructive in capturing the mood of the times.

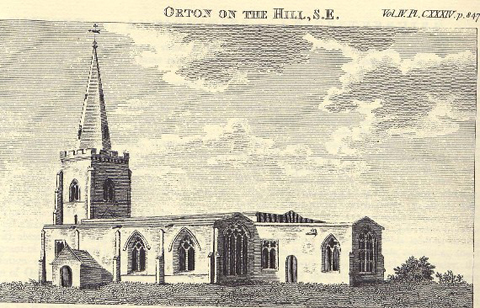

Roger Porter, vicar of Orton from 1638, was ejected from his living in 1647. He was certainly put to great inconvenience for his open support for the king, ‘imprisoned three times and often plundered’. His troubles were exacerbated by having to support a wife and a huge brood of children. The ‘intruder minister’ (his replacement) Mathew Mathews, complained in July 1647 that when he went to officiate at the church he could not gain entry as the key of the church had been taken from the clerk. On the following Sunday when two officials went to take possession of the vicarage house Porter's mother denied them access. Mathews and two sequestrators later complained that Porter had sued them for removing the glebe corn.

The parsons placed in the most perilous situation were the incumbents of Packington, about a mile from Ashby-de-la-Zouch, where the lordship was in the possession of Lord Hastings. Here, the incumbents, the elder Thomas Pestell, who had the living from 1622, and his son and namesake, who replaced his father as vicar in 1644, were both openly sympathetic to the king’s cause. A letter written to Sir George Gresley about 1645, confirms that the elder Pestell had by then ‘long resigned his means of Packington to his eldest son; and had been robbed and plundered of goods (almost all) five several times, besides cattle’. On 20th April 1646 they were both jointly charged before the County Committee on twelve articles, including observing ceremonies, being ‘great libertynes’ , keeping ‘beagles and houndes’, and ‘damaging their neighbours’ property without redress’. In his defence the elder Thomas declared that he was not bound to reply to the charges as he was within the articles for the surrender of Ashby though he nevertheless attempted to defend himself. As regards the keeping of hounds he explained that Lord Hastings and his brother sometimes boarded with him and hunted, he had been given the hounds but had given up hunting long since. As for the charges of employing scandalous preachers and of plundering his neighbours, he claimed that most of these accusations were score settling by old enemies such as Joseph Johnson who promoted a case against him in High Commission in 1633 and a certain Stacy whose daughter he had refused to marry some 34 years earlier.

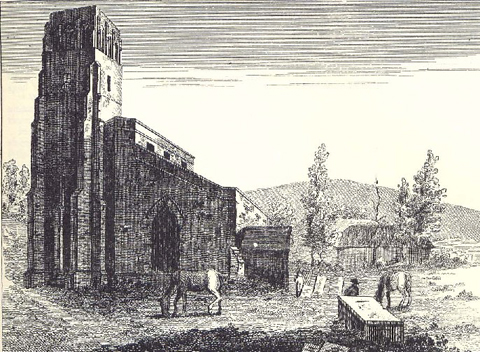

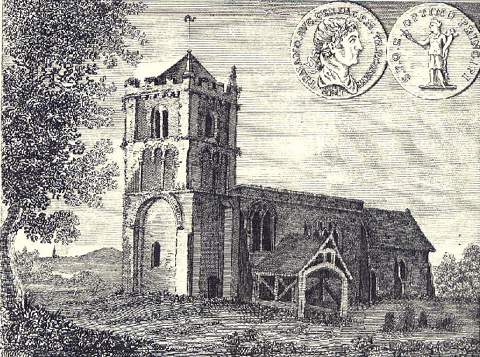

Packington Church

The younger Thomas Pestell, vicar of Packington in 1644, before fleeing to Ashby, took a more active part in the conflict, and only narrowly escaped hanging after the battle of Worcester (‘the rope was about his neck’ according to his sister). His earlier career, preaching before the King at Oatlands and later before the ‘Council of King and Lords at York’, naturally brought him to the attention of the Committee who in March 1647 appointed an intruder minister to replace him. His grand-daughter, Mrs Sarah Muggleston, recounts his dramatic ejection by Parliamentary soldiers in a letter reprinted by John Nichols:

‘I have heard my mother say, Mr Pegg (which was the usurper’s name) came into Packington church in time of divine service with a group of soldiers, with their pistols cocked, and held them to my grandfather’s breast when he was reading prayers. He said. “Gentlemen, use no violence; here is none will resist you”. So they took away the Common Prayer Book, and laid a ballad in its place. My grandfather went and sat with his wife and children, and heard Mr Pegg read an account of all his faults, for which he was turned out, concluding, And so God has justly spewed him out of his mouth! Mr Pegg then went into the pulpit, and took his text, “I am hath sent me unto you”. [Nichols p. 927].

Mrs Muggleston added: ‘My grandfather was several times imprisoned for christening a child and marrying, and for not keeping parliament feasts and thanksgiving days’. Pestell of course mounted a spirited defence against these charges levied against him. As chaplain to the earl of Huntingdon at Ashby he claimed that he was able to get some of his neighbours released. In answer to charges of observing ceremonies and taking down the rails in Packington Church, he claimed they had been taken down by his father while he was serving as curate at Cole Orton. He protested his willingness ‘to remain in the ministry of the church of England under such orders as should be by law established, asserting that he prayed for Parliament as ‘the great counsell of the Land’.

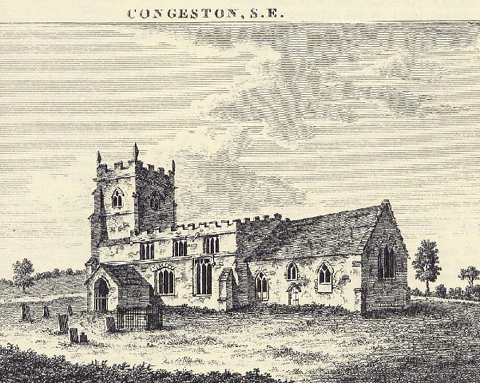

Swepstone Church

Such equivocation was commonplace, though difficult to sustain for more serious charges such as those levied against Francis Standish, the vicar of Swepstone charged by the County Committee on nine articles in March 1646, including ‘scouting in the night with the king's forces’. Francis’ problem was that he had been taken in arms in Lichfield Close after its capture by the Parliamentarians, though he strenuously denied this, declaring in his defence that he had only stopped there on his way to collect goods previously left there on the way to visit his mother in law in Cheshire, and explaining that he and his companion were trapped in the city when they fell sick two or three days before the siege. Altogether Francis was called to account for his visits to three royal garrisons, at Ashby, Tamworth and Lichfield. When charged with giving General Hastings a grey mare and donating £50 to the Ashby garrison, he declared that Hastings had sent for the mare which he dared not refuse assuring his accusers that he ‘never gave a farthing’ to the garrison. He also denied charges of paying tithes to the enemy at Snarestone in 1644, and of getting warrants ordering his parishioners to give tithes to the royalist garrison. Francis pleaded that the offences were all committed three years or more ago, ‘before men could well recollect themselves and resolve what course to take’, and before there were any Parliamentary ordinances to guide them. He also asserted that he had gone to Leicester after it was taken on a Christian errand, ‘in simple pity of heart’ and he reminded his accusers that no charges had been made against his manners or doctrine and that none of his neighbours had complained of personal injuries.

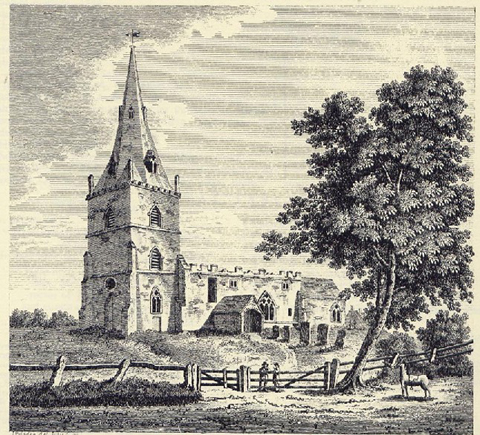

Whitwick church

Michael Crosley, vicar of Whitwick from 1612 appeared before the County Committee in 1646 on eleven articles, including a damning allegation that he had described Parliamentarians as ‘traitors, worse than Gunpowder plotters’. He too was accused of observing ceremonies, and keeping some of his parishioners from the sacraments for three years because they would not kneel. There were further charges of his frequenting alehouses for being ‘a swearer’, and for saying that ‘there was little difference between Roman and Anglican religions’- all indicative of royalist or Papist leanings. In 1649 he was listed among those charged with being ‘disaffected and scandalous’.

Richard Dawson, the rector of Congerstone in 1641 was charged with nine articles including refusing the sacraments, neglecting the Directory and parliamentary fasts. On 19th November, 1646 he had to answer for profaning the Sabbath by allowing games, for playing cards at home and for being ‘brutishly drunk’. He denied all of these charges, saying that he stopped his brother’s children from playing cards when they stayed with him and that he had visited the Ashby garrison only to help one of his neighbours in trouble.

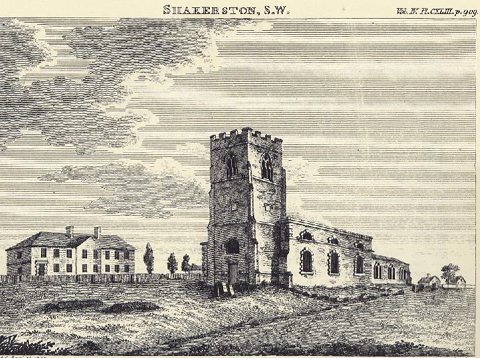

John Hodges the vicar of Shackerstone was charged with nine articles in 1646 and ejected in November of that year. Most damning was the charge that he had spent four months at Ashby when it was a royal garrison. He was also accused of frequenting an alehouse on Sundays, being ‘a companion with fidlers and singers and doth at their meetings tell them that if they will sing bawdy and ribaldrous songs … he will conjure and thereupon hee did pull out of his pocket a paper, but what was in or what it concerned none can tell for hee kept it in his hand’. Hodges was suspected of being Papist, for his description of them as ‘true subjects’ and for apparently saying ‘in discourse …it was a pity the common sort of people should know the word of God’.

Nailstone church

John Hubbock, rector of Nailstone was another royalist minister charged by the County Committee. The offences listed included charges of preaching against the Puritans, threatening those not standing at Gloria, profaning the Sabbath with games and the familiar charge of frequenting alehouses. But Hubbock had also to answer a charge of being ‘a common whoremaster’ following his presentation in the spiritual court for this offence. He was further accused of producing a warrant to bring in Parliamentary supporters to Bagworth House when it was held by the Royalists, and was heard to say ‘in private, he hoped the Scots would join the king to make a mighty army he then would recover his living’.

Higham

Thomas Sturges the vicar of Higham on the Hill was charged with eight articles for scandal and drunkenness. In December 1646 it was alleged that one Sunday he was so drunk that that he was unable to officiate. The prosecutors also claimed that he read printed sermons, that he refused to give the sacrament except at the rails and that he let his family and others play games on Sunday.

Henry Gilbert of Clifton Camville in Staffordshire was referred to be examined for his living in 1647, then cited by the House of Lords because of a letter he wrote to his parishioners warning them to be extremely scrupulous about paying tithes to his successor, 'to tie him unto such Conditions and upon so good Bail that when the Laws shall once again renew their force, you may come to no damage'. In March 1648, when he was cleared for delinquency and his visits to the Lichfield garrison, Henry Gilbert was one of many who claimed he had been plundered, imprisoned and forced to pay 'great sums' for his release.

Clerical connections sometimes helped to alleviate the hardships of removal, as in the case of Thomas Whelpdale, the rector of Newton Regis, in Warwickshire, who was placed with his family in a house at Ingleby in Derbyshire by Sir Francis Burdett, who presented him in 1647.

Little seems to be known of Gabrielle Rosse, the vicar of Norton juxta Twycross, the incumbent listed for the Civil War period up to 1658. Presumably he sided with Parliament or at least kept strictly to his clerical duties and avoided political or religious confrontation. He and others, such as Abraham Mould in Appleby, must have known many of the royalist clergy of neighbouring parishes and communicated with them, or at least heard about their activities. Most of the royalist clergy around Appleby successfully defended themselves against charges of neglecting their duties. Although Thomas Sturges was one of the few who were unsuccessful in his petition to secure the profits of his living in 1660, the Restoration saw most of Abraham Mould’s malignant or scandalous neighbours honourably re-admitted and restored to their parsonages.

Sources

Particular acknowledgement to A.G. Mathews, Walker Revised. Being a Revision of John Walker’s Sufferings of the Clergy during the Grand Rebellion, 1642-60, Oxford, 1948, 234-245, 322-3, 366, with the assistance of Simon Harratt of Ibstock. John Nichols, Antiquities of the County of Leicester, Vol. III, Part ii, Appendix. and Volume IV, Part ii for references to individual parishes and church illustrations.

© Alan Roberts, 2004