Appleby History > Alan Roberts > 16th Century Scandal

A 16th Century Scandal

Archdeaconry court records - a different slant on 16th century Appleby

by Alan Roberts, with drawings by artist Frey Micklethwait from

Pumpenbil in NSW, Australia

John Petcher of Appleby was brought before the Leicester archdeacon's court on 29th October, 1597 charged upon a "common fame" of having committed adultery with Sara Winter, wife of Robert Winter, one of his neighbours. We later find that John “purged himself” of this offence “as well by his own oath as by the oaths of four of his honest neighbours”, was acquitted of the charge and “restored again to his good name”.Leics. Record Office, Archdeaconry Court Proceedings, 1D41/4/673a)

Some two or three dozen pages of court depositions or witness statements for this case survive among the records of the Lincoln archdiocese. The vast records of the archdeaconry courts are of particular interest to local historians because they provide fascinating insights into the behaviour and social attitudes of the villagers. Their revelations of innocent merrymaking, gossip, intrigue and common roguery are a reminder that the villagers shared our human strengths and failings. These records can indeed provide an alternative view of village life, a corrective to history based upon the bare bones of census and taxation records.

“Bawdy Courts”

Apart from church and probate business the archdeaconry courts dealt almost exclusively with moral offences. Their twin preoccupations with illicit sex and defamation earned them the popular name of "bawdy courts". The broad scope of the courts’ jurisdiction and diversity of clientele ensured that every town and village in Leicestershire had its quota of offenders. Indeed in some cases whole communities were called forth to give evidence and the investigative dragnet was widened even further by the courts’ admission of hearsay evidence, encouraging litigants to heap scorn on their accusers to bring prosecuting witnesses into disrepute.

|

The archdeaconry court with case in progress - drawing by Frey Micklethwait based on Alan's article Click the image for a larger view |

Elizabethan Social System

Robert Winters’ allegations against John Petcher can thus be set in context of the village social system. Appleby in Elizabethan times was still an open field parish with between 300-400 inhabitants. Robert and Sara Winter occupied a smallholding as tenants of Edward Griffin, lord of the manor of Great Appleby. Petcher was a sheep farmer whose own wife had died about a year before the presentments and whose goods were worth only about ten pounds at his death in 1621 (will and inventory of John Petcher, 1621). Edward Taylor, the principal witness was a more “shifty” inhabitant, perhaps a cottager or vagrant with connections to the labouring poor. The court also questioned witnesses from outside the parish, including Hugh Draiton, an Atherstone alehouse-keeper, and three Swepstone farmers who were in Atherstone on the day that Edward Taylor claimed to have seen John and Sara cavorting together.

A “Wayward wife”?

Petcher was brought before the court on presentments based upon “common knowledge”, but most of the evidence is circumstantial. He was reported to have been in the company of Sara Winter on several occasions, and to have frequented Robert Winter’s house in his absence. A certain Galfridus Meassen from the adjacent village of Measham is alleged to have told Richard Aldret of Appleby that he saw John and Sara “together between two rye lands in Measham fields” (though he does not say what they were doing there.) However the principal articles of the indictment are more concerned with Petcher’s luring Sara “by diabolical persuasion and enticements of the flesh” to local towns and fairs – specifically to the market towns of Ashby, Atherstone and Leicester. This mention of fairs is especially interesting, as Q.R.Quaif found from his study of Somerset Consistory Court records, “wayward wives” and their lovers often met secretly in alehouses and at fairs. These festive occasions provided opportunities for illicit liaisons denied to couples within the narrow watchful world of their own parish. (Wanton Wenches and Wayward Wives 1979 pp. 128-)

Adultery, intrigue and bribery

|

It seems that Sara was particularly attracted to fairs, and her husband may have already tried to put a stop to her philandering, for there are reports of his having “put away his wife”. This could explain why she was staying with Nicholas Taylor and his family in the days leading up to the Atherstone fair. Robert may have been trying to “entrap” her when he offered a reward to Edward Taylor “to watch Sara and Petcher to take them in adultery together”. This would explain too why Edward’s kinsfolk took her to Atherstone. There is also an accusation that Robert had a hand in a crafty scheme whereby Nicholas Taylor tried to persuade Sara to start a suit against her husband on the grounds that he had refused to cohabit with her – a ploy to entice Petcher to lay out money for a court action. And there are rumours that Robert bribed Edward Taylor, by providing fuel, bread and money to secure him as a witness against Petcher. (721c)drawing by Frey Michaelthwait based on Alan's article

|

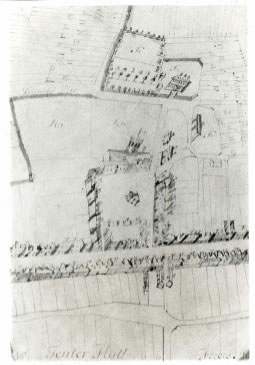

An early 18th Century map of Atherstone showing Watling Street and the market square, probably little altered from 1597 when farmers from Appleby and the surrounding villages gathered for the fair in 1597. (Published by permission of Warwickshire County Record Office, maps p7) Click the image for a larger view |

Annual fair at Atherstone

The court proceedings revolved around events which took place on the fateful afternoon of the annual fair in Atherstone, and centred around the alehouses with which the town was particularly well provided. (There were in fact 32 alehouses in the town in 1720, VCH Warwickshire IV, p. 126). Hugh Draiton’s alehouse was probably right in the market square, shown in a map of 1716 (Warw. Country R.O. ref. P7). A mid sixteenth century court roll lists Hugh Drayton as a customary tenant paying 1s 3d for a burgage plot in the town, while a Christopher Drayton paid rent for a barn in the market place and five acres of land (B. Bartlett, History and Antiquities of …Manceter, 1791, pp 150-3). Draiton’s alehouse was evidently well frequented by local villagers and the festive atmosphere is captured in witnesses’ depositions. Arriving on the scene Edward Taylor, the key witness, was barely able to conceal his delight upon discovering that John and Sara were sitting together in the alehouse. But his enthusiasm seemed to have exceeded discretion for not long after his arrival, perhaps after a few ales, we hear he “did openly before witnesses slander John Petcher…and called him whoremaster”. This was a serious accusation which had to be carefully examined.

The events which followed can be pieced together from witness depositions. By mid afternoon the fair was at its height and a merry throng had crowded into the alehouse. The downstairs rooms were “greatly frequented with guests going in and out continually”. Several groups of people sat eating and drinking in the hall which joined onto the parlour where John and Sara sat with Nicholas Taylor and his wife. It’s not certain how long the couple were left alone together after Nicholas and his wife withdrew. However, as it was pointed out, although the parlour door was closed it was unlocked; so there was little chance of their being left undisturbed. Much was made of the suggestion that “most men coming into a victualling house on a fair day, especially if they lack a place to sit in, do usually look into a parlour where guests use to be”. If they couple were fornicating, it was argued, surely the landlord, his wife, his servants or his guests would have known!

The court was rightly sceptical about Taylor’s claim to have “taken” the couple in adultery and his supposed refusal of sixpence from Petcher to keep silent about the matter, since no one else came forward to verify this tale. Also there is strong evidence that Taylor spent most of the afternoon drinking with Hugh Draiton in a nearby alehouse. It is hardly surprising that his allegations were described as expedients for him to “release or excuse himself, and not for any truth that is in the matter”.(673a)

|

Interior of an Atherstone Alehouse - drawing by Frey Micklethwait based on Alan's article, and partly based on The Angel Inn, Hugh Drayton's alehouse in Atherstone Click the image for a larger view |

Witness Accounts

The sworn depositions of the three Swepstone farmers, Richard Dudley, William Chilwell and Thomas Burrows, all support this judgement. According to their account they were sitting in the hall when Nicholas Taylor’s wife entered “meaning to see whether the said Petcher and Sara were naughty together”. But she “could not, nor did see them in any such sort and was reproved of the said Dudley for her peeping in”. Dudley’s admonition suggests that the Swepstone farmers did not think well of spying on their neighbours. All three swore that they had been in the alehouse or in the street outside all afternoon and they had not set eyes upon Edward Taylor or his wife in that vicinity. Furthermore they avowed that their beasts were so crowded against the alehouse that no one could possibly have approached the parlour window from outside.(721c)

Elizabethan Criminality

The case against Petcher thus turned into an attack on the character of the principal witness. Edward Taylor is scornfully caricatured as “a man that hath not land, lease, stock or possessions…to maintain his wife and children”, who had “for very poverty, idleness or some other cause given over his occupation of blacksmith wherein he was trained and brought up” taking up “bad, shifty and unhonest practices”. He had already confessed himself before witnesses to adultery and was commonly known to be a cozener or defrauder of men. A long catalogue of his alleged crimes include allegation that he robbed a woman upon the highway, with a threat that if the woman informed upon him he would say that she gave him money for sexual favours. He is also accused of stealing candlesticks from a house in Ashby and barley sheaves from Appleby fields. He was accused of extorting money from the young men of Appleby with a document purporting to give him authority to take soldiers and one occasion he apparently tried to steal a horse from George Smaller’s stable at Snarestone, “and was riding away with him, and had ridden so away if the said Smaller had not met him and scared him”.

If these stories were true it is amazing that Taylor had so far escaped imprisonment or hanging. Indeed, it appears that he had spent time in Leicester gaol but he had persuaded the keeper to allow him “to go awhile into the town” and absconded, despite a solemn promise to return. His wife Helen, who was “commonly accompted to be light fingured and of no credit or reputation at all” had also spent time in Ashby gaol for stealing a pair of shoes. It’s possible Taylor’s criminal tendencies were exaggerated to blacken his name and destroy his credibility as a witness, but these accusations do lend support to the notion that there was a great reservoir of “tolerated criminality” in Elizabethan times. Local ne’er-do-wells were to some extend shielded by their neighbours. In fact one Somerset magistrate complained in 1596 that as much as four fifths of crimes that had been committed went unreported (G.R. Elton, introduction to J.S. Cockburn’s History of English Assizes, 1558-1714, p. 107)

The Social Sanctions of Church Courts

The case against Petcher is typical of its kind. It is first mentioned in the Liber Actorum or Instance Court Act Book for October 1597. Witnesses were still being examined the following March and April, after which the case seems to have been abandoned. Ten years later, following an archdeaconal visitation, Petcher’s name is included on a list of those suspected of fornication who had been overlooked by negligent churchwardens (Leics. Record Office 1D41/11/30 f121).

Clearly the effectiveness of these courts in suppressing immorality must be questioned. The courts of quarter sessions and assizes meted out punishments that included imprisonment, branding, amputation and hanging for crimes against the state - but the archdeaconry court had to rely on social sanctions. Convicted adulterers and fornicators were usually made to perform “penance in sheets” which according to William Harrison in 1587 needed replacing with “some sharper law” since it was “counted as no punishment at all to speak of, or but smally regarded of the offenders” (Description of England, ed. G. Edelen, Ithaca, 1968, p. 189). It’s not surprising that the villagers often treated the church courts with contempt (Elton, in Cockburn p.3)

Petcher’s acquittance owes much to sworn depositions against the principal witness and the hint of Winter’s own complicity in using the court to entrap his wife.

In Conclusion

The investigation throws some light on the petty intrigues of Elizabethan village life in Appleby, but of course there are many unanswered questions. The witnesses’ depositions reflect ambivalent attitudes towards sexual misbehaviour- ranging from vehement denunciation on the one hand to apparent indifference on the other. The court proceedings can penetrate only the surface layers of this tightly-knit world at irregular intervals, yet they provide a strong impression of social intrigue and surreptitious behaviour in seemingly “quiet” villages, not unlike that of our own times. We do not learn whether Sara and John continued to keep company together, or whether Sara returned to live peacefully with her aggrieved husband, or whether Edward Taylor was dragged before the assizes for his roguish ways. But we can be sure that the Appleby villagers had their own ways of settling disputes and reconciling parties at enmity outside the courts. We are left with the impression that they lived socially more eventful, emotionally more unsettled and sexually more active lives that one might at first suppose from studying economic records alone.

©Alan Roberts 2000