Appleby History > Alan Roberts > Open Fields & Enclosures

Open Fields and Enclosures

Appleby’s Open Fields in the Early Modern Age

by Alan Roberts

|

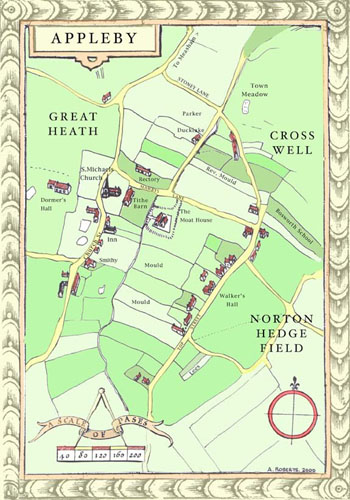

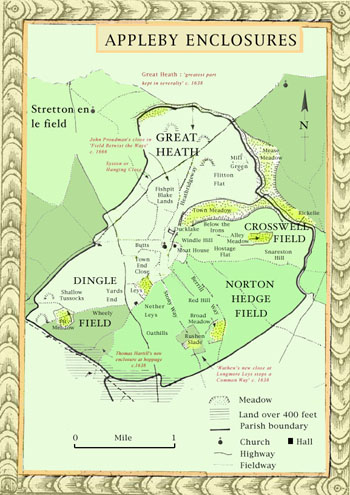

By the mid sixteenth century 'the three great arable fields of Great and Little Appleby' were being farmed communally by the inhabitants of both townships, who continued to share the same church and parish. Seventeenth and eighteenth-century wills and indentures commonly refer to these fields as Norton Hedge, Dingle and Crosswell respectively. Two earlier surveys, a fifteenth-century manorial terrier and a glebe terrier from 1606, describe the relics of a medieval open field system containing six separate cropping areas.

The areas referred to in the manorial survey as 'le feeld nygh Norton', 'campo juxta Snarston' and 'le cleyfelds' are almost certainly the same three arable fields mentioned in sixteenth century wills. The 'herth' and 'heith' fields (renamed Bridgehill and Moore Field in the 1606 terrier) denote lands newly won from the heath. An additional field, identified in the 1606 terrier as 'Meadow Brook', was probably the town meadow.

By the early 1600s the Appleby farmers had a communally organised three-course rotation of grain, legumes and fallow. A 1628 lease of the demesne, for example, refers to lands 'in the corne or pease fields' which were to be fallowed 'by the husbandry course and usage of the [common] fields'. Cropping practices are also outlined in some of the farmer's wills. For example, in 1602 John Wright, who described himself as a husbandman, owned a field strip at 'Magge Baker Pitt lying by Matthew Swayne's headland' which his brother-in-law had promised to till and manure. He also owned lands at Red Hill and Sandy Furlong sown with peas and barley. His brother, William, in 1609 had no less than 39 of these field strips or selions scattered over the parish, together with a single enclosure. Pasture closes are rarely recorded in the wills before 1620. Apart from Cruistom Close which belonged to William Swayne, only three enclosures at 'Witghiton', 'Weetfurrow' and 'Dingle Close' are identified. However the enclosed 'parcels of ground' on the heathlands attest to the presence of individually owned grazing plots. It seems likely that some of these enclosures were 'home closes' or paddocks carved from the common field arable. The exact boundaries of the open fields and the proportion of arable to pasture at any one time are difficult to determine. Comparative surveys seem to suggest that the actual areas under tillage could change from year to year in response to cropping adaptations.

One of the most important farming activities was stock fattening. This was carried out on specialised pasture closes or 'common greens' (Annescote and Hooked Green), on 'meadow leys' and on the Commons. The greens, which are recorded in the parish from as early as the thirteenth century, were choice enclaves of permanent pasture especially set aside for this purpose while the meadow leys were strips of meadow occasionally put down to arable. Arable field strips could easily be converted to pasture leys for tethered beasts, which may perhaps explain the absence of a fixed stint on the commons. This lack of any constraint on the number of beasts is revealed in the pronouncement of the minister and churchwardens in 1606 that 'their ys no certayne Stynt, neyther of longe tyme hath beene, but euery man keepeth what pleaseth him'. The meadowland, in contrast, was carefully partitioned and allocated annually, proportionable to the yardland, as at Wigston Magna. A fifteenth-century piece of meadow called Alymedow, for example, reappears in 1621 as Allemeddas close, a tract of enclosed ground containing several freely disposable 'parcels of ground'. The extent of piecemeal enclosure is not known, but there is no doubt that the process of conversion was well under way by 1600. At the same time the emphasis was not entirely on livestock husbandry; efforts were also being made to improve soil fertility through marling and muck spreading in accordance with recommendations in the practical husbandry manuals.

The Farming Economy of the Parish

Appleby's pre-industrial farming economy can be partly reconstructed from wills and inventories. An examination of livestock and crops recorded in the inventories of eighteen farmers who left good valued at more than £15 between 1580 and 1610 reveals that all except one - the tailor, George Shilton – owned ploughs or harrows, which shows they were involved in arable farming. They seem to be a representative sample of smallholders farming perhaps one or two yardlands apiece.

Four of the householders in this list (Richard Mould, Richard Taylor, John Pratt and William Robinson) have the same surname as the copyholders on Paget's demesne in 1546 – men with one or two virgates. About a third are listed as tenants on Bosworth School lands paying rents ranging from 3d to £1.3.4 in 1598 (rental DE 43/456). Of the remainder, a few including Thomas Wright, John Wilson, George Shilton, Walther Backhouse and Thomas Frisby were from Little Appleby, which suggests that they were probably copyholders on Moore's demesne. Most seem to be smallholders holding a customary messuage and tenement and perhaps leasing additional land as required.

Fifty per cent of the inventory-makers kept sheep, with flocks ranging in size from the two kept by George Shilton to John Peat's flock of 100. Eight out of ten had horses and about six out of ten kept pigs. Some of the horses were probably draught horses used to pull ploughs, carts and barrows, while the pigs provided flitches of bacon for household consumption and for market. Nine out of ten of those listed grew wheat and three out of ten had peas on the premises. The need for additional feed for livestock is revealed by stocks of hay and fodder in six out of ten inventories. It is also interesting to note that about half of those who left inventories in the period had other income-earning sidelines in addition to their crops and livestock. The most popular of these subsidiary activities were beekeeping, ale-brewing and cheese production. Several householders harvested hemp and flax which could be spun into sheets or plaited to make collars and harnesses. Overall, the accumulated evidence relating to farming in the wills and inventories up to 1620, suggests that the inhabitants of Appleby had evolved a complex and flexible system of mixed-farming, evenly balanced between livestock and tillage.

Piecemeal Enclosure by ‘the richer sort’

But this system was changing. Over the course of the seventeenth century the farming landscape of Appleby, like that in other parts of the midlands, was being slowly transformed by piecemeal enclosure. The initiators, in this instance, were a small group of 'the richer sort' in alliance with the Moores at Appleby Parva. Yet despite the decline of tillage, the common fields survived as an integral part of the farming system, until they were dismantled by the Parliamentary commissioners in 1772. On the eve of final enclosure Appleby still had 750 acres, or a quarter of the parish, in open field arable. A comparison of field strips recorded in church glebe surveys between 1606 and 1697 suggests that the physical structure of the fields remained intact between these dates. The reorganisation took place within the existing framework.

The scale of the enterprise can best be seen by looking ahead to the final result. The 1772 enclosure award, which is the most authoritative source for the eighteenth-century landscape provides a comprehensive account of the pre-enclosure landscape, describing 535 ‘ancient inclosures’, 81 messuages, 11 cottages and three homesteads. By 'ancient' the commissioners mean to signify that the enclosures pre-dated the recollection of the oldest living inhabitant. So, presumably, over 1,800 acres, or two thirds of the parish, was either enclosed or held in severally by 1700.

The population of the parish expanded considerably between 1600 and 1700. Bishop Wake’s census taken between 1705 and 1716 records 100 families, representing an increase of around twenty per cent on the estimate derived from the census of 1603 and this probably provided a compelling incentive to increase crop production.

Most of the enclosures re-allocated in the 1772 award were small blocks of field strips, of one or two acres (mean 1.16 acres) which had already been partly amalgamated. Wills from the latter half of the seventeenth century indicate that there was still a core of hereditary smallholders with field strips which had been passed on through several generations, as in Wigston Magna. For example, a succession of Moulds occupied a tenement known as 'Ducklake house' from 1558 to around 1689 when it appears in the possession of Abraham Mould. Comparisons with Wigston should not be taken too far, however. The records relating to land trafficking and severally conversions point to a comparatively high turnover of smallholders, so there is not much sign in Appleby of a ‘conservative’ group preventing enclosure.

The ‘Decay of husbandry’ in Appleby

|

The evidence of a gentry-led enclosure movement comes from a list of interrogatories drawn up in connection with a Star Chamber suit initiated by the rector of Appleby in 1636. These articles give a long catalogue of complaints against Charles Moore and others 'of the richer sort', leaving no doubt that their enclosures were a sorely contentious issue in the parish. The defendants, who include in their ranks prominent yeomen like William Stanton, Richard Wathew, Richard Walker and Thomas Spencer, stand accused of having encroached upon the commons for the past forty or fifty years.

Charles Moore, lord of the manor of Little Appleby, is challenged for his failure to convene the manorial court and arrest the general 'decay of husbandry' within the parish. The descriptions of alleged 'disorders' clearly show that alterations had been made to the farming landscape within the original field structure and that the richer sort were in the vanguard of those who 'combined one with another to make exchanges for enclosing'. Among other alleged abuses the defendants were accused of turning arable to pasture, and of making enclosures from the common pastures and meadows without the consent of their neighbours. Their inroads upon the commons sparked angry protests from their own tenants. In Little Appleby the inhabitants complain 'that they have few or no sheep upon the commons though their forefathers kept many', while in the northern half of the parish the large areas enclosed and kept in severally on the Great Heath aroused fears that the whole of this marginal grazing ground would soon be withdrawn from common usage.

Disputes over the common beast pastures or 'herdsman's walks', the land set aside for the use of the poorer inhabitants, reveal that not all conversion was a simple changeover from arable to pasture. The common pastures in Little Appleby, for example, had become so straitened by enclosure and ploughing that the herd was not able to be 'driven from one part of the commons to another without danger to the cattle and great spoil of corn growing near thereunto’. As a result, an area 'that was wont to maintain fourteen or fifteen score head of cattle' was not able to maintain half this number. Meanwhile the wealthier inhabitants were exploiting another source of pasture by bringing their cattle onto the fields as soon as the May harvest was taken in, some having by common knowledge 'three times more than they should in regard, of their farms'. These accusations suggest that the Appleby farmers were facing a dilemma felt throughout the midlands at this time: that of finding sufficient pasture for the great cattle once the sheep had been let loose on the fallow. Their solution was to press every spare acre of grass ground into service. Allusions to the ploughing up of greens and leys at Hardfurlong and the reduction of cattle in the 'narrow Greenes' indicate, at the same time, a compensatory conversion from pasture to arable.

Despite this litigation, the Moores continued to consolidate their hold on the parish and to increase their stake in the farming economy. By 1772 there were only four proprietors with more than 100 acres of open-field arable. The Moores who possessed more than 500 acres together with common rights to 14 ancient messuages had become by far the largest landholders in the parish. Their ascendancy to a position of unrivalled influence owed much to Sir John Moore, the younger son who became a Restoration Lord Mayor of London and who provided the funds for the building of Appleby Free School, on land adjacent to the hall in Little Appleby. The Moores continued to consolidate their holdings by land purchases, including the purchase of Euseby Dormer's lands opposite the Church and of a close from John Carpe worth £300. In fact their unbridled enthusiasm for converting arable to pasture caused the parson to complain in 1700 that they were harming the church by reducing the tithe revenue. As he wrote to Sir John,

Your nephew, George Moore, by enclosing large parts of our open fields is harming the church. He has tendered as recompense one penny for a close of many acres; if this is accepted it will reduce the revenue of the church in a short time from £100 per annum to £20..

Although these changes to the traditional pattern of landholding can easily be exaggerated, they probably accentuated the widening social difference between the richer yeomen and gentry who profited from enclosure, and the more numerous group of smallholders and landless labourers who did not.

Sources and Notes

Inq.Post Mortem (Henry VII) III, 33, 1041-2; Edmund Appleby's inventory is reprinted in G.G. Astill, 'An Early Inventory of a Leicestershire Knight'. Midland History, 2 No. 4 (1974), 274-83.

For field names see wills of John and William Wright, L.R.O. wills,

1609/29; 1609/80; indenture DE 797 (1733).

B.L. Sloane MS, xxxi, 9, (printed in Nichols IV, 438); Heathlands are revealed by the furlong names: breichflat refers to broken land, blakelondes to black or bleak lands, quarell is a derogatory term for difficult land.

L.R.O. Lease of Appleby Magna manor, DE 43/104.

L.R.O. wills, John Wright, 1606/83, William Wright, 1609/60, John Pratt, 1597/107; William Houlden, 1613/114; indentures, Susan Butler (1610), 42D/ 31/16; DE 43/108

In Lutterworth the open fields changed shape while the comparative acreages under crop remained constant owing to 'lack of constraints ... as to which lands should be cropped': J.D. Goodacre, Lutterworth thesis, (Univ. Leicester Dept. English Local History) p. 116.

Lincoln Record Office: 1606 Appleby Glebe Terriers 15 D55/43, 1D 41/2/9;

Cf. Reference to Crasswalgrene and Fulwalgrene in the Sloane terrier; 'lands' and 'leys' were used alternately: See J. Thirsk, English Peasant Farming (London, 1957), 89, 97, and B.K. Roberts, 'Field Systems of the West Midlands' in Studies in the Field Systems of the British Isles, eds. A.R.H. Baker and R.A. Butler, (Cambridge, 1973), 203; Cf. Mention of West Wellegrene in Appleby Parva and Grenweybull in grants to Roger the Smith (1262) and Peter Petcher (Temp. Edward I) respectively: HMC Hastings MSS, I, 47-8.

Meadowland wills, John Erpe, 1679/133; For a further account of Wigston's system of allocation see Hoskins, Midland Peasant, 68, 164-5.

Allemedas close in wills, Alice Blith, widow,.1621/13.

References to muckheaps in inventories of Margery Gilbart, 1588 (PR I/9/133), Richard Wright, 1588 (PR I/9/81), John Pratt, 1591 (PR I/12/142), Richard Taylor, 1592 (PR I/9/81).

Appleby Enclosure Award L.R.O. 15D 55/44; All acreages given have been calculated from this award.

Ducklake house in L.R.O. wills, William Mold, 1558; Joseph Mould 1694/92; Abraham Mould, 1689 (P.R.O. PROB 11/160/397); Richard Petcher farmed a holding passed down by his grandfather (L.R.O. wills, 1695/39); Other hereditary associations are revealed in Appleby glebe terriers (I5D 55/43, 1D 4112/9); At Barkby in NE Leicestershire one in every five householders owned their messuages and tofts, fewer still owned land in the common fields: Sue Postles, 'Barkby: the Anatomy of a Closed Township' (Leicester Uni. unpublished M.A., 1979), 12; A lack of evidence of hereditary links led J.Z. Titow to assert that 'the notion of an hereditary class of smallholders belongs to the same brand of fiction as the typical manor': 'Some differences between manors and their effects on the condition of the peasant in the thirteenth century', Essays in Agrarian History (op. cit.) I, 45;

Star Chamber interrogatories L.R.O. 15D 55/41; I am indebted to Prof. T.G. Barnes of Berkeley, California, for locating the filing of this bill in Folger MS, V. a. 278. Prof. Barnes is of the opinion that the case may have been desultorily prosecuted for one or two years, then abandoned.

For solutions for pasturing cattle see Joseph Lee, 'Considerations Concerning-Common Fields and Enclosure (op.cit.), 6.

By 1882 Appleby Hall estate had expanded to 4,500 acres in 20 farms spread over four adjacent parishes: L.R.O. Estate Prospectus, 1882, DE 646/4.

Moore’s career in Nichols IV, 440-1; A more detailed account given in The Dictionary of National Biography, XIII, 805-6.

L.R.O. Moore Correspondence, DE 1642/13, DE 1642/35-6; purchase of land for Appleby School, 28 D55/67. Letter from Isaac Mould to Sir John Moore, 15 October, 1700: DE 1642/47.

©Alan Roberts, November 2000