Appleby History > In Focus > 26 - Church Restorations Part 1

Chapter 26

Appleby Church Restorations

Part 1: The Church Before Restoration

by Richard Dunmore

In the 19th century Appleby Church underwent two periods of restoration and remodelling which resulted in the church of St Michael and All Angels which we know today. To understand the restorers' work, we need first to look at the two earlier forms of the building for which evidence, both physical and written, remains. Built for one form of worship, after the Reformation the church was adapted for another.

As built, the church was designed to support a Catholic form of worship, i.e. the Latin rite of the mass. This was celebrated by the priest at the altar of one of the two chancels, dedicated areas set apart from the laity who used the rest of the building. With the ascendancy of Protestantism over Roman Catholicism in the 17th century, the function of the building changed. The mass was rejected as superstitious and incomprehensible. The emphasis now was on reading the Bible in English from a lectern and preaching sermons from the pulpit. The building interior was altered accordingly. The main chancel was effectively walled off and the body of the church turned into what has been called a 'preaching box', filled with seating for the parishioners and with pulpit and lectern prominently located against one of the nave pillars.

The Original 'Catholic' Building

The basic structure of the church building which we see today dates from the early 14th century. This is evident from the reticulated tracery of the windows, the quatrefoil piers and the double-chamfered arches, all typical of the Decorated Gothic style of that period. One particular feature of the tracery is the use of ogee (i.e. S-shaped) curves which were popular in the 14th century (1).

Apart from these stylistic aspects, other features of the building have been found which confirm the original Catholic form of worship of the medieval period. Much of what is known about the earlier state of the church building is due to the record left us by John Nichols writing c.1811 (2).

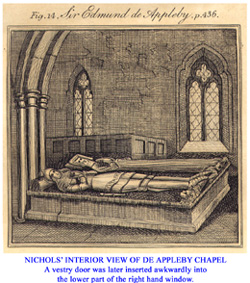

Two Chancels

A feature of the eastern end of the church was the presence of two chancels side by side. I have previously noted that the north aisle chancel, also known as the de Appleby Chapel,is the oldest part of the building and may be the site of an earlier Saxon church building. Nichols recognised the antiquity of this chancel by referring to it as the Appelby's aile or chancel (2) containing, as it still does, the original de Appleby family tomb. As other de Appleby burials followed, this chapel became effectively a family mausoleum and chantry chapel (3).

Nichols described the arches (still existing) of the chancel and the nave and noted that the North aile was formerly parted from the chancel by a row of stone pillars, and a wainscot of wood, part of which yet remains. This must refer to a screen between the north aisle and the old north aisle chancel. He continues: There is now no appearance of any mural [i.e. wall-] seats in the chancel; but there is an old wooden seat or stall, whereon are some small remains of carving.

In this earliest period, each chancel would have had its own altar. There were two piscinas, basins for washing the mass vessels, which are no longer visible but may still be within the walls filled in and plastered over: In the South wall a half-quatrefoil piscina; and a similar one in the North wall, a parabolic arch of about two feet in height, and one foot deep in the wall (2). Presumably each chancel had its own piscina. They would be built into the outer walls because of the necessity for drains to allow the washing water to be reverently disposed of.

In a medieval church the chancel arch, separating the chancel from the nave, was where a rood screen would be situated. However, by Nichols' time, the upper part of the screen had been plastered over. There remained openings at ground level. The chancels were regarded in medieval times as set apart for the priest. Here is Nichols' description of the screen as he found it:

A massive stone-screen divides the nave and chancel. The lower part is open; the upper part covered with lath and plaster... No traces remain of any rood loft. This church having, for the most part, been kept in good repair, no wonder, from the many coats of plaster, white-washing, pointing &c that almost every antique mark should be obliterated and lost (2).

The medieval stone screen across the chancel arch, perhaps ten or twelve feet high, was clearly still standing although heavily altered by the reformers. Above it in the early period, would have been a rood, consisting of a large raised crucifix flanked by statues of the Virgin Mary and St John, all standing on the top of the screen, i.e. on the rood loft. From Nichols' account it is clear that all the figures had been removed, as they had from every church in the country at the Reformation.

There are other medieval features of the church still visible today on the outside of the building, of which Nichols was unaware and which have not (to my knowledge) previously been reported.

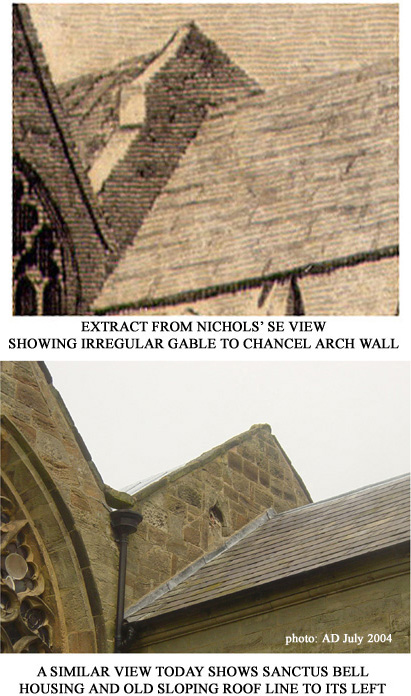

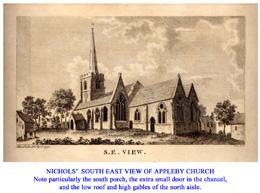

The Sanctus Bellcote

High on the outside of the building, on the eastern side of the chancel arch wall and visible from the south-east, is a recess formed by a double ogee arch. The recess is shallow and appears (viewing from the ground)to have been filled with material which is gradually eroding. The raised modern chancel roof line crosses the lower part of the recess and an old, lower, gable line is visible to its left. The recess is not shown in Nichols' south-east view of the church. Instead, the gable end has an unusual step at this position . Nichols' SE View is compared with a modern photograph below.

The conventional position for a sanctus bell in a medieval church was in a bellcote or turret at the junction of the nave and the chancel. The bell was rung at the most sacred parts of the mass – during the sanctus (Holy, holy, holy...) and during the consecration of the bread and wine.

The position and size of the recess visible on Appleby Church, although off-centre, must identify it as the remains of a sanctus bellcote. It would have projected above the nave roof, incorporated in the step in the gable above the chancel arch. The bell would have been rung by a rope from within the body of the chancel. After the Reformation the bellcote was redundant and it would appear that, by Nichols' time, the bell had been removed and the housing filled up with rubble and mortar. It may have been plastered over but remained within the step of the gable invisible to Nichols' artist.

This of course explains the curious step in the gable shown in the SE View. In a later restoration, with changes to the roofs, the gable line was straightened and built up to its present height leaving the filled-in bellcote as a feature within the wall, although not easily visible. Recent erosion of the filling has made it more apparent.

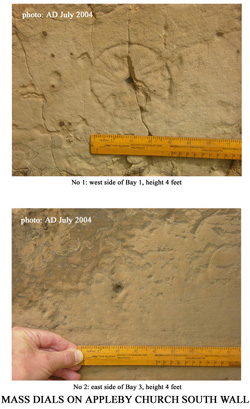

Mass Dials

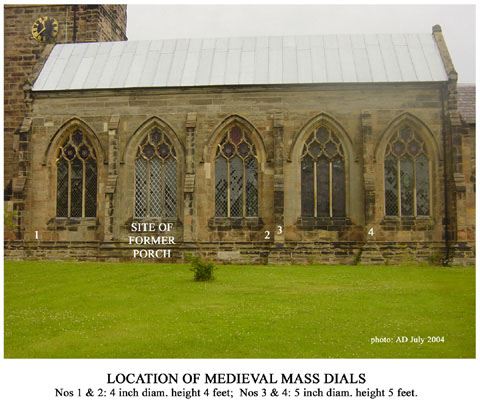

The other major evidence of the pre-Reformation use of the building, which has hitherto been overlooked, is the remains of medieval mass dials on the south facing exterior of the building. These were a crude form of sun dial, each consisting of a circle with particular radii, incised or scratched on to south-facing stonework and usually located near an entrance doorway. In the centre of each dial is a hole to take a simple pointer, or gnomon, the shadow of which, falling on the radii, gave an indication of the time. Their use on a church building was to mark the time of services rather than to show the time accurately (4).

There are four dials on the south-face of Appleby Church and they appear to be arranged in pairs. There are two on the wall positioned symmetrically either side of the former south porch. These, Nos. 1 & 2, are approximately 4 inches diameter and at a height of 4 feet above the present ground level. The other pair, Nos. 3 & 4, are on buttresses and are approximately 5 inch diameter and 5 feet from the ground. All have suffered from weather erosion and No 2 is particularly badly eroded, although recognisable. Nos. 1 & 3 have received some physical damage, the latter apparently relatively recently.

The positions of the dials on the church building and pictures of the dials themselves are shown below:

|

|

Building Sequence

The existence of these four mass dials, together with the evidence of Nichols' illustrations, enable deductions to be made about the sequence of building of the porch and buttresses against the south wall of the church building.

Nichols' SE View (see below) shows the south porch with no buttresses (Nos 2 and 3) adjacent. These two were added in the first 19th century restoration when the porch was removed. So skilfully were they constructed that they cannot be distinguished from the medieval originals but archaeological evidence obtained by David Parsons in 1975 confirmed that they were indeed built during the restoration work (5).

Mass dials were positioned where they would be in sunlight. Nos. 1 and 2 seem to have been positioned on the south wall either side of the porch where one would catch the morning sun (No. 2) and the other (No. 1) the evening sun, each in turn avoiding the shadow of the porch. The construction of buttresses cast them into shadow and necessitated the construction of new dials, Nos. 3 & 4, standing out on the sun-lit faces of two of the buttresses. The need for two replacement dials may have been because No. 3 was found to be rapidly overtaken by the shadow of the porch on winter afternoons.

Parsons observed that the demolished porch was probably not contemporary with the south aisle wall. It is therefore possible that there was an original mass dial close to an unsheltered south doorway. This dial would have been completed unshaded by any projecting walls. It would have been destroyed when the porch was built and replaced by the surviving dials Nos.1 and 2.

If this deduction is accurate, then we may conclude that the south wall was built at first without buttresses or porch. The porch was built over the south doorway in the medieval period before dials Nos. 1 and 2 were made. Later again, with the construction of strengthening buttresses, the resulting shadows rendered dials Nos. 1 and 2 useless and made necessary the construction of the new dials, Nos. 3 and 4, on the sun-lit faces of two of the buttresses.

The Church After The Reformation

Nichols' account and illustrations indicate the extent to which the building had already been changed from its original design into a building suitable for Protestants after the Reformation. The post-Reformation church described by Nichols in 1811 would be recognisable to us today, with its nave, side aisles, chancel and north aisle chancel (now the vestry), as well as the tower and spire, but there were many differences in detail from the present state of the building.

Chancels used for Burials and Memorials

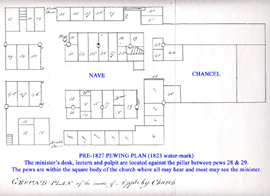

There was as yet no organ and the vestry was probably under the tower. The present carved wooden screens were not put in place until the 1870s, so the two chancels would have formed one continuous area extending under the separating arches. Nichols makes no mention of an altar in either chancel but somewhere there would have been a simple table for Communion. The only seating in the main chancel reported by Nichols was an old carved wooden chair, as noted above. An 1823 pew plan (see below) shows that there was also a pair of box pews on either side of the chancel arch with views of the pulpit through the screen.

The care and use of the north chancel was in the gift of the Bosworth School governors as lords of Appleby Magna manor. Nichols observed some pews which had been put up some years since over some levelled altar-tombs near the north wall,presumably for the use of Bosworth School governors or their tenants; and that there had been a stone seat and inclosure within man's memory (2). Apart from this seating, the north aisle chancel was mainly occupied by tombs and memorials, the oldest being the tomb of Sir Edmund de Appleby, which still survives. The tradition of using this chancel for manorial burials continued long after the Reformation. Nichols noted that the pews hid the levelled altar-tombs of the Dormers who occupied land of Appleby Magna manor during the 17th century. There was also an illegible stone slab at the east end of the north aisle against the wall under the parish chest (6).

Much of the main chancel area was also occupied with graves and memorials. Some of the latter survive on the south wall above the (later) choir stalls. These belonged to the various patrons and rectors of the 17th and 18th centuries, predominantly from the Mould family. Thomas Mould bought the patronage (i.e. the right to appoint the rector) in the year 1610 and was himself rector. His memorial is over the south chancel door. Although some of the carving has been damaged, presumably in the Cromwellian period, the inscription written in Hebrew, Latin, Greek and English survives. He died on 26th September 1642 (Latin: transmigravit – literally 'passed away' - a surprisingly modern euphemism). The English couplet reads:

Behold my thread is cutt, my glass is runne:

And yet I live, and yet my life is done.

Other Moulds followed: Abraham (1642-83) who, like Thomas, was his own patron; Isaac (1683- 1721) and Jacob ( 1721-31). The patronage remained in the family or with relations until 1793.

The whole floor area of the church was regarded as a suitable place for burials, especially for the more wealthy supporters of the church. The most eminent of these were the Moores, who purchased Appleby Parva manor around the year 1600. The position of their vault at the east end of the south aisle is noted by Nichols in relation to the burial of George Moore (1688-1751) (6). Amongst others buried in the church and listed by Nichols are the first headmaster of Appleby School, Mr George Waite (d.1725) and Mr Joseph Farnell, surgeon (d.1757). All the burials must still be there, hidden under the later pews and paving.

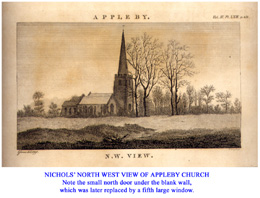

Exterior

The roof line of the building was lower than it is today but the gable ends of the side aisles were relatively high. The main external difference however was in the position of the entrance doors to the building. The principal entrance was through a south porch, attached to the second bay of the south aisle from the west. Across the church and opposite this was a door forming an entrance on the north side. Both of these positions are now occupied by large windows.

|

|

| Click images for larger views | |

Nichols' SE view (above) shows that there was a small doorway where the Rector's seat now is, i.e. on the south side of the chancel and one bay west of the surviving medieval Gothic chancel door. The pre-restoration seating plan shows a box pew located in this corner of the chancel and the small door would have provided direct access into it (see also below). Nichols' interior view (below) also shows that there was no doorway under the north-facing window of the chapel, as there is today in what is now the vestry (7).

|

|

| Click images for larger views | |

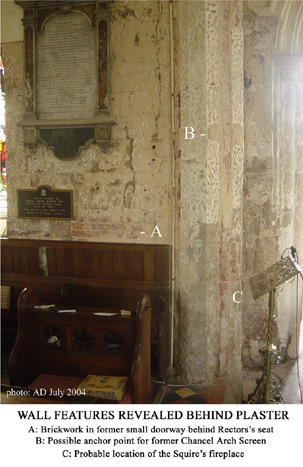

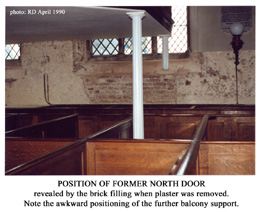

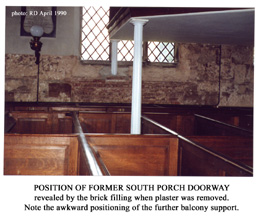

Recent Revelations beneath the Wall Plaster

The removal of plaster from areas of the internal walls (pulpit area 1950s, side aisle walls 1990, chancel arch 2004) has revealed or confirmed changes to the pulpit, the chancel arch and the positions of former doorways. In the restoration work, although the exterior was mainly faced with stone the inner portion of the wall was made good with brickwork which was plastered over. The exposed brickwork shows the positions of the old doorways very clearly.

The chancel arch is revealed to have vertical courses of brickwork making up its bulk and altering the shape of the original moulding. A break in the stonework crossing this line of bricks, approximately 9 feet (2.7 m) from the nave floor, may mark the upper level of the screen, at the level where the rood stood. However, the adjacent respond (arch support) of the main arcade shows fixing holes up to at least 10 feet (3.0 m) so it may have been even higher. Whatever its precise height, the screen in its plastered condition must have presented an extensive visual barrier between nave and chancel.

The Small Door

With wall plaster removed, the brickwork filling the former small doorway can be seen protruding above the panelling behind the Rector's desk (see picture). It is rectangular in shape, 3 ft (0.9 m) wide and 5 ft 6 in (1.7 m) above the present floor. However the chancel floor was clearly raised during later restoration work so the actual height of the doorway above the original floor was 6 feet (1.8 m). From the outside, a much-weathered lintel may still be discerned over the doorway.

The door's non-Gothic shape suggests a post-Reformation, functional purpose. The pre-restoration pew plan (see above) shows box pew No. 45 in this south-east corner of the chancel backing on to pew No. 1, which would have been used by the squire and/or his family. Nichols records that the door of a pew over the Moores' vault was marked CM 1692 TM. All the Moores' pews and the external door may have been contemporary with this (2).

Keeping the Squire Warm

Click for larger view |

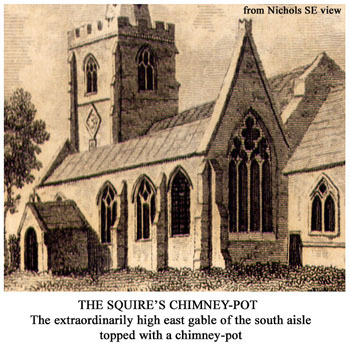

The external door would have allowed servants to come and go attending to the family's requirements, but what exactly were the servants' duties in church which required a door? The answer may be found from Nichols' south-east view of the church which shows the gable at the east end of the south aisle above the Moores' corner of the church. This gable rises to an extraordinary height, far above the south aisle roof line. Close inspection of the engraving shows that the gable is surmounted by a chimney pot.

It is reasonable to conclude that there was a fireplace in the corner of the squire's pew between the chancel arch and the first arch of the south arcade i.e. immediately behind where the lectern stands today. The small doorway in the chancel wall was close behind this, in pew No.45 (see door picture above). The chimney would be concealed in the fabric between the responds of the two arches and in the slope of the gable leading up to the chimney pot. Incidentally, heating for the rest of the congregation would have to wait until the later restoration work.

Returning to the servants, they would be required to look after the squire's pews and this would include lighting and maintaining the fire. The adjacent small doorway would give them easy access, essential in bringing coals and removing ash without having to go through the body of the church.

The North and South Porch Doorways

Removal of plaster along the north and south aisle walls in 1990 revealed brick fillings, beneath the second windows from the west, where the north and south doorways had been. The width of the brickwork in the north is narrower than that in the south. The wall opening on the south side would have led into a porch roughly the width of the later window, whereas there was a simple doorway on the north side. Some of the north doorstep stonework survives on the outside beneath the rather inferior window. By contrast the window inserted in the south wall is almost indistinguishable from the medieval ones.

|

|

| Click images for larger views | |

Adapting the Building for Protestant Use

It has been remarked that congregations listening to Bible readings and sermons needed to be comfortable. Along with the removal of altars, the installation of pews was widespread in the 17th century (8). The interior of Appleby Church must have been reordered around that time to enable the church to be used more effectively for its newly reformed purpose. Who made the necessary alterations to bring this about? With their long period of patronage of Appleby church and rectory after the Reformation (1610-1793), the Moulds, whose memorials may be seen in the chancel (see above), must have been responsible. They visually blocked off the chancel, installed the pulpit, lectern and clerk's desk in the body of the church and encouraged the plentiful provision of seating. The Moores in particular made themselves comfortable.

Square Shaped Preaching Box

The overall space occupied by the nave and side aisles is an almost perfect square, of side 56 feet (17 m), and most of the seating was distributed throughout this area. The seating plan (shown above) dating from c.1823, i.e. before the 19th century restorations, clearly shows the lectern, pulpit, desk and seating of a 'Protestant preaching box' or hall typical of the 17th century (8) (9). Screening off the nave at the chancel arch reinforced the sense of enclosure. Apart from three open benches all seating was in boxes. Although there were aisles, these boxes were arranged in an ad hoc fashion, lacking overall symmetry. The seating therefore appears to have been tailor-made for the requirements of individual families, who had either paid for their own boxes or arranged to occupy them for an annual rent.

For most of the time the hidden chancel area was hardly used in this period. Holy Communion is likely to have been celebrated only three times a year, the minimum requirement stipulated in the Prayer Book.

Galleries

In addition to the seating boxes shown on the plan, there was a gallery at the west end of the church erected, Nichols tells us, for the scholars of Sir John Moore's School (1697) and on the north side there was a gallery for the psalm-singers (2). The bases of the supporting columns of the school gallery are marked on the plan just in front of the rear boxes 46 and 51. Examination of the floor flagstones shows the footprints of supporting pillars in both the north and south aisles, indicating that there was a gallery in the south aisle also. Nichols also says that the floor of the church and chancel was paved with brick.

The desk, lectern and pulpit for clerk and minister were situated next to the fourth pier (column) from the west of the arcade on the north side of the nave. It may have had a triple-level construction (10) although the first plan for restoration, dated c.1832, which retain a pulpit and lectern in this position, appears to have only two levels (11). The pulpit was positioned prominently against the first pier, i.e. one whole arch-span forward into the nave compared with the present position against the chancel arch respond (half-pier). In the old position, the preacher would have been surrounded by his congregation seated in the pew boxes below and galleries above. This pier was stripped of its plaster in the 1950s revealing holes where the old pulpit had been attached.

Neglect

The religious and political turmoil of the 16th and 17th centuries led to a change in attitude towards the care of church buildings and maintenance was often neglected. By 1800, it became clear that, despite all its whitewash, restoration of Appleby Church was vital if it was to regain its usefulness. From 1827 to 1832 major work was put in hand to renovate the building concentrating at first on the roof, nave and aisles. The renewal of the chancel arch opened up access to the chancel although it was not refurnished at this stage. Later in the 19th century, with the return of more ceremonial worship (albeit in English) the long-neglected chancel was reordered. This was done in the years 1871-72 with the installation of choir stalls and other fitments in the Gothic style. The pulpit was replaced by a smaller one on the north side of the chancel arch. These 19th century restorations will be detailed in Part 2.

Notes and References

1. N Pevsner, The Buildings of England, Leicestershire and Rutland, Penguin 1960, reprint 1977; Appleby pp 47-48. The Decorated division of the medieval Gothic style of architecture covers the period from c.1290 – c.1350; tracery is the intersecting ribwork in the upper part of the windows; reticulated refers to tracery composed of circles and ogee lines where circular lines change smoothly from convex to concave (i.e. S-shaped); quatrefoil refers to the cross-sectional shape of the piers (columns) rather like a four-leafed clover. See Pevsner's excellent Glossary.

2. J Nichols, History and Antiquities of Leicestershire, IV part 2, 1811: church p 433-8; old chancel p.436; piscinas p.433; screen p.433; old chancel stone seat p.434 note 1; Moores' 1692 pew p.434; gallery p.434

3. In Focus 6 & 7 ,The Origins of Church and Manor

4. The Mass Dial section of the British Sundial Society is at www.sundialsoc.org.uk/massdials.htm

5. David Parsons, An Emergency Excavation at Appleby Magna Church, Leicestershire, TLAHS, L, 1974/75, pp 41-45. A 3m x 3m area was dug against the the 3rd buttress and bay (from the west), ahead of essential drainage work along the south wall. Surprisingly the mass dials appear to have been overlooked.

6. J Nichols, op. cit.: monumental inscriptions pp 436-8; Dormers and Moulds p.436; Moores p.437

7. J Nichols, op. cit.: illustrations: exterior views opp. p.431; interior de Appleby chapel opp. p.434

8. Simon Jenkins, England's Thousand Best Churches, Allen Lane/ Penguin,1999, pp. xviii-xx

9. Ground Plan of the inside of Appleby Church, c.1823 (watermark), LRO, 15D55 28/54

10. R J Eyre, The Nineteenth Century Restorations at St Michael & All Angels, Appleby Magna, LAHS, LXI, 1987.

11. Appleby Church Pew Plan, c.1832, LRO, 15D55 55/30

©Richard Dunmore, August 2004

Postscript to In Focus 26

Appleby Church before Restoration

In the last article I described the two earlier forms of the building's interior:

- the original medieval layout with its 'Catholic' chancel furnishings and

- after the Reformation, the 18th century 'Protestant preaching box' with its dominant pulpit and pews.

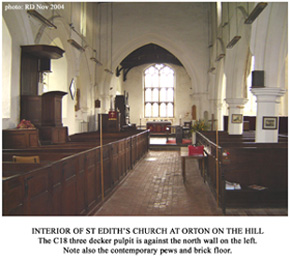

These internal fittings have not survived at Appleby, so on a recent visit to St Edith's church at Orton on the Hill, I was delighted to find a relatively unrestored building with 14th century piscinas, an 18th century three decker pulpit and contemporary pews intact.

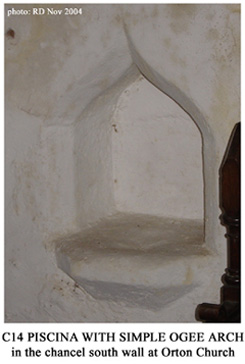

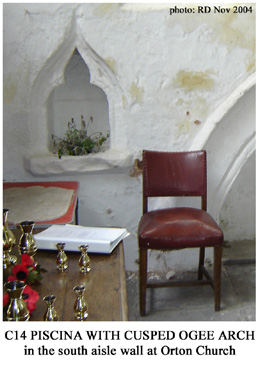

Nichols' describes two piscinas at Appleby. These were basins for washing the mass vessels and built into wall alcoves: In the South wall a half-quatrefoil piscina; and a similar one in the North wall, a parabolic arch of about two feet in height, and one foot deep in the wall. The half-quatrefoil piscina would have been a half clover-leaf shape, i.e. rounded rather than pointed at the top. Parabolic is not a recognisable architectural term, but it must mean some form of simple Gothic shape.

St Edith's church dates from the 12th century, a little earlier than St Michael's at Appleby. The piscinas there have ogee (S-shaped) arches - one of them with cusps. Although not precisely the same shapes as those at Appleby described by Nichols, they enable us to imagine what Appleby's piscinas might have been like.

|

|

| Click images for larger views | |

The surviving three decker pulpit at Orton dates from about 1760 and is really splendid. Although no longer used, it has been preserved in its original location part way along the north wall. The pews come from the same period and the flooring, also contemporary, is brick. According to the church guidebook, until fairly recently, the seats in the pews were arranged to face the old pulpit.

|

|

| Click images for larger views | |

Appleby's pulpit may have been built a little earlier than Orton's, but must have been very similar and dominant with its overhead tester or canopy, which I suspect acted as a sounding board to improve the acoustics. Appleby's three-decker was built against the first pier of the north arcade, i.e. one arch forward from the position of the present pulpit. As at Orton, there were contemporary pews and the flooring was brick too

©Richard Dunmore, November 2004

Previous article < Appleby's History In Focus > Next article