Appleby History > In Focus > 28 - Church Restorations Part 3

Chapter 28

Appleby Church Restorations

Part 3: The Restoration of 1829-32

by Richard Dunmore

I Mary Moore do make this codicil to my will this 29th day of January 1823: I give to the Revd Thomas Jones Rector of Appleby in the county of Leicester and to George Moore of Snarestone two of the Commissioners for repairing the Parish Church of Appleby one thousand pounds in trust that they will apply the said sum of one thousand pounds towards the substantial and effectual repair and new paving of the said Parish Church trusting that the Parishioners will contribute liberally to the same purpose.

Mrs Mary Moore lived at Appleby Hall, the name lately adopted for Appleby House which had been reconstructed in 1796 (1). She was the widow of Revd John Moore, the brother of the Squire George Moore. Their only child had died in infancy and Mrs Moore left generous legacies to members of the extended family. She also made the above handsome bequest to Appleby Parish Church just before she died in 1823. The executors and administrators of the will were two of the Squire's younger brothers John and Charles Moore. Charles Moore was a barrister and he appears to have carried out the executors' duties (2).

As related in the last article, spurred on by Mrs Moore's generous bequest, the parish set about restoring the church. However after a change of architect and disagreements over costing with the (new) architect and the building contractor, who then withdrew, progress came to a halt in 1827 (3). The situation was exacerbated by the deaths in rapid succession of Charles Moore in March 1827 (4) and George Moore in June 1827. The latter was succeeded as squire by his son George who was still a minor. In his will, George Moore senior appointed guardians for the children and trustees for the estate (5).

The Faculty and Plan

The diocesan faculty authorising the restoration work is dated 17th March 1827 (6). Although much of the work carried out in the years 1829-32 follows this plan, it is quite clear that the restorers went considerably beyond the agreed specification. No evidence has been found to suggest that permission was sought to carry out this extra work. The most likely (and charitable) explanation for this lapse is that the remaining manager of the restoration work Rector Jones also died, in August 1830, only one year into the project and the understanding of the rules to be followed was lost with him. Revd John Echalaz, who took over promptly as the new rector, would have been reliant upon churchwardens who could hold office for as little as one year (7). Enthused by the project, Mr Echalaz may well have instigated ideas of his own without being aware of the correct procedures. Be that as it may, substantial changes were made.

The faculty, which is accompanied by detailed specifications for the contractors, authorised the following:

- - taking down the old reading desk and pulpit and replacing with new ones in the same position,

- - removing and replacing all the old pews, seats and stalls in the body of the church; this resulted in the neat symmetrical layout that survives today,

- - provision of 51 seats on 17 free-standing benches down the centre aisle,

- - building a new 'loft or gallery' at the west end to replace the old school gallery,

- - making a new roof partly in lead and partly in queen slates (the latter over the chancel and chapel),

- - to 'new ceil' the church, ie make a new ceiling,

- - to 'new floor' with stone,

- - to form flues under the floor for warming,

- - to raise the walls 2 feet or thereabouts (to accommodate the new ceiling),

- - to repair stonework and 'new glaze' the windows,

- - to make a new entrance at the west end under the tower,

- - to renew and repair the window tracery,

- - to block off the north doorway but leave in place the south porch; this is apparent from the plan accompanying the faculty.

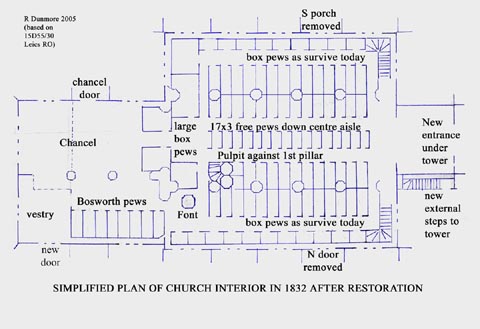

However, a plan of the building drawn when the work was near completion (see picture below), shows that the south porch was removed and that both north and south entrances were replaced by windows designed to match the other large windows of the north and south aisles. These changes were apparently not authorised.

Work begins on the Building Shell

With such a large and bold undertaking it was clearly necessary to get the outer shell of the building remodelled first, so that a new roof could be put in place to keep out the weather. The existing roof was removed and the walls raised to a suitable height to accommodate the elaborate ceiling which was planned.

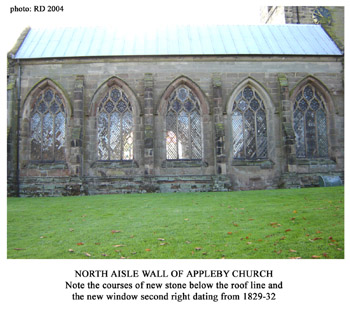

Examination of the exterior of the building shows several courses of new stone running round the whole building immediately beneath the eaves.

Hopton Wood Stone

The source of the dressed stone blocks used to raise the height of the walls is likely to have been Hopton Wood quarry near Wirksworth in Derbyshire. R J Eyre has identified a notebook to be in Rector Jones's hand-writing. In this the rector wrote: Take Potter [the first architect] to Mrs J Moores to inspect the Hopton stone in her hall (8). This refers to Mrs Mary Moore and the work that she and her late husband Revd John Moore had undertaken at Appleby Hall. Mrs Moore, daughter of Frances Hurt Esq, came from Alderwasley, also near Wirksworth, so the their use of Hopton stone at Appleby Hall and later at the Church should not be surprising (9) (10).

Click for larger view |

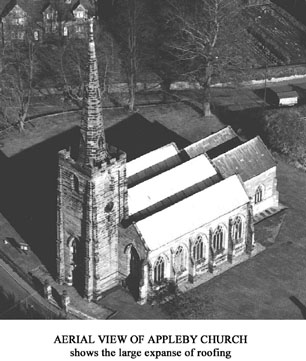

The aerial view of the church shows the sheer size of the roof which is not readily apparent from the ground. This picture (taken before the renewal of the roof of the 1980s) shows the roofing material from 1829-32. There are six sloping surfaces of lead sheet over the three aisles; and four sloping roofs of imperial slates over the chancel and chapel.

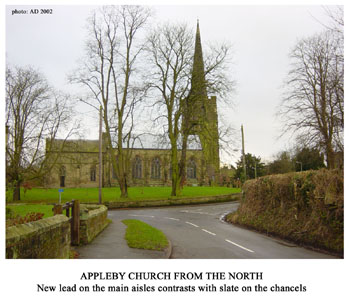

The familiar general view of the building from Measham Road was taken after the 1980s roof renewal. The slates on the chapel roof contrast with the bright new lead on the main roofs.

Click for larger view |

Click for larger view |

The closer view of the exterior of the north aisle wall shows the new stone quite clearly. Above the top of the buttresses are three courses of a lighter coloured stone.

Old North Doorway

Also visible in this view is the new window which replaced the north door (second window from the right). Again lighter coloured stone was used particularly on the window arch. The horizontal line of moulding is missing under the new window and it is slightly smaller than the other windows. The reason for this is that the north-door bay was slightly narrower than the others. The mason must have constructed the new window in proportion to the bay width rather than copying the other windows. The result is not completely satisfactory and some of the work rather slip-shod. As well as the missing section of moulding, parts of this wall have been patched with cheap plastering, especially under the new window itself.

Click for larger view |

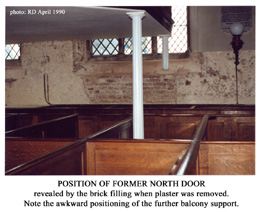

Inside the building, in 1990, plaster was removed from the lower part of the walls in a second attempt to solve the problem of dampness in the walls. (An earlier attempt to improve the drainage outside the walls had proved ineffective - see below). The removal of plaster on the inside of the wall shows the brickwork filling for the old north doorway. This was constructed directly onto the old doorstep, which is just visible at the base of the outside wall.

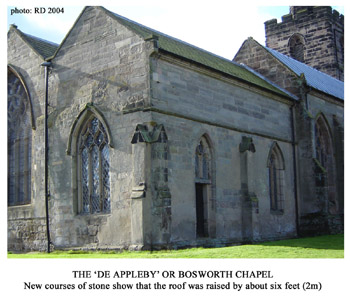

The Chapel

Click for larger view |

The de Appleby Chapel is the oldest part of the whole building and was the responsibility of the Lord of the Manor of Appleby Magna. In the early 19th century the governors of Bosworth Grammar School still held this position and their co-operation was obtained for the renovation work.

The original roof line of the chapel was considerably lower than that of the rest of the church. The picture shows that seven courses of new stone (about 6 ft in height) have been added to the top of the earlier north wall above the line of moulding marking the eaves of the earlier structure. An old stone gable end forms part of the wall above the chapel east window (a short length of sloping roof line is still visible) and the upper part of this wall has been reconstructed and topped with new stone. The resulting position of the short piece of horizontal moulding which turns the corner seems distinctly odd. Repairs to the outer walls at this end of the building, on the chancel walls as well as the old chapel, are also unsatisfactory. No doubt done to save costs, deteriorating stonework has been patched with plaster rather than properly replaced with stone. Some of this work may have been carried out at a later date and not necessarily at the time of the 1829-32 restoration.

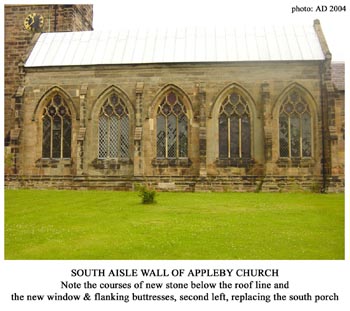

The South Aisle Wall

The raising of the roof line of the south aisle wall by three courses of masonry matches that of the north side of the building (see picture below). Restoration of this wall generally appears to have been carried out more thoroughly than elsewhere around the building. Stone has been replaced with stone, although there are one or two unfortunate colour changes.

The Old South Porch

Click for larger view |

The best quality of workmanship however is around the new window which replaced the south porch, ie the second window from the left. Not only the wall around the new window, but also the new buttresses either side fit in perfectly with the rest of the south facade. The lower courses of moulding have also been faithfully reproduced and the overall result is a remarkable unity of style. It should be noted that the second window from the right has also undergone considerable restoration.

The excellent workmanship of this area is in marked contrast with the poor work on the north side of the building. Why should this be? Perhaps the answer lies in the fact that the south porch was dismantled and there was old stone available to be reused, stone which was almost certain to match the south wall and its buttresses.

Archaeological Excavation

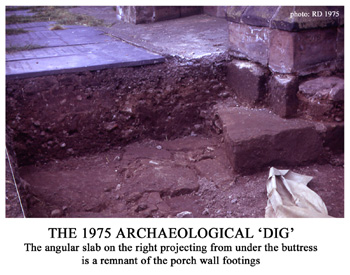

Apart from the documentary evidence of the church records and old drawings of the building reproduced by Nichols, there is archaeological evidence for the foundations of the porch obtained in 1975. At that time the Parochial Church Council embarked on a drainage scheme running along the outside of the south wall to try to alleviate dampness in the wall. As the ground was to be disturbed, Mr David Parsons the archaeological adviser to the Diocese was invited to investigate the area.

The trench opened was about 3m square, located in the third bay and incorporating the buttress on the eastern side of the former porch ie the third buttress from the left.

Beneath the topsoil was a 'robber trench', ie a trench back-filled with debris after the removal of a structure such as a wall. It contained fragments of building materials and was lying N-S, in line with the third buttress. This buttress was built on a limestone slab projecting out from under the church wall. The robber trench was interpreted as being the footprint of the east wall of the porch. The slab is a remnant of the porch footings, the rest have been removed with the demolition of the porch (11). My photograph, taken at the time, shows this angular slab projecting from underneath the buttress. The position of the buttress, built on top of the footings slab, proves that it was newly built after the demolition of the porch.

Click for larger view |

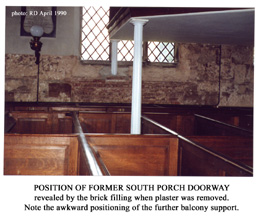

With the later removal of internal plaster from the lower part of the walls, the infill of brickwork of the south porch doorway was revealed (see picture), as was that of the north doorway described above.

It was part of the restoration job specification that the in-filling, where it would be hidden by plaster, was to be carried out in brick while external work was to be executed in stone. Removal of internal plaster in 1990 shows that this instruction was followed throughout (12).

A New Entrance

The closure of the north and south entrances was made possible by the provision of a west entrance (see picture) with a new porch formed in the area under the tower where formerly the vestry had been located. The new arrangement was part of the architect's plan and conformed to the current fashion of providing the main entrance at the west end of the church. Local churches newly built at that time, such as St John's Donisthorpe, Holy Trinity Ashby and Christ Church Coalville, all feature a western entrance (13).

The arrangement at Appleby no doubt suited the gentry who, arriving at church in their carriages, could pass directly up the steps from the carriageway straight into the building. The provision of a pair of classical gate piers to flank a wide set of steps added a suitable element of grandeur (14). Wrought iron gates have not survived. What may not have been anticipated was the strength of the prevailing westerly wind from which the new porch affords little protection.

The porch was styled in keeping with the grand interior (see below) with the insertion of a simple vaulted plaster ceiling. This necessitated raising the level of the belfry floor immediately above. The awkward result is that the floor was raised above the bottom of the west window, below which the new doorway was inserted.

New Groined Ceiling

Click for larger view |

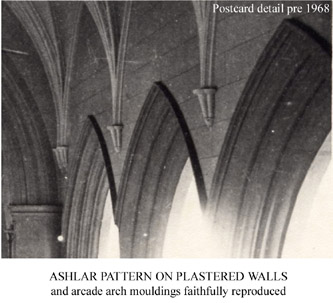

The purpose of raising the exterior walls of the building was to make room for the elaborate groined ceiling. This ceiling was part of the design of the first architect Joseph Potter of Lichfield and the design was perpetuated in the final plans drawn up by John Mason of Derby who was responsible for most of the architectural design work. Whether Mason made any significant alterations to the ceiling is not clear (15). The elegant plasterwork has not been without its critics. Brandwood for example comments that distinctly awkward rib-sections are employed to achieve a level ridge in the aisles (16). Appreciation of neo-classical work is a matter of personal taste and many people find the Appleby design impressive (see pictures).

The internal walls themselves were replastered with simple rectangular score marks to imitate ashlar masonry and the piers were plastered faithfully reproducing the original architectural moulding. This became apparent when plaster was stripped from part of the north arcade in the 1950s. The reason for plastering the walls in the first place lay in the poor quality of the underlying stone and this would have been apparent early in the life of the building. John Nichols, writing before 1811, complained about the plastering obscuring every antique mark (17). Natural stone with a warm colour is most appropriate in a medieval building but, with the stone badly deteriorating, the use of plaster became essential.

The elaborate design of the ceiling raises the question of how the work was carried out. The technique for such work was to create sections of the ceiling groins on a mould at ground level. These were then lifted into place and fixed on a barrel-shaped frame of timber and laths constructed below the roof. Not every contractor would have been able to tackle such a difficult project and the result is to the great credit of the builder William Matthews.

The Interior : Pulpit and Pews

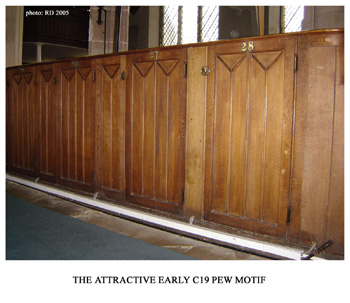

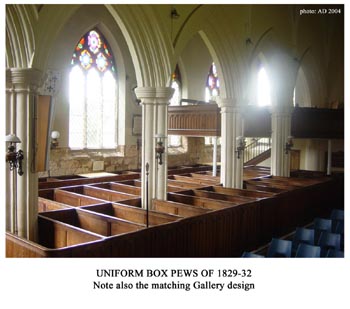

Most of the pews occupying the main body of the church surviving today date from this period. As can be seen from the plan, orderly narrow boxes stretched from the back (west) of the church only as far as the first piers of the arcades ie up to where the pulpit was located on the north side. Forward of that position, large pews backing on to the chancel area were provided for the gentry, the Moores and probably the rectory family, who had occupied boxed seats in these positions previously.

The squire's fireplace and service door must have been removed and plastered over at this time (see In Focus 26). A new pulpit replaced the old one in the same location but this did not survive the further alterations of the 1870s.

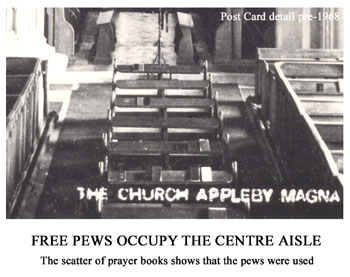

Pew rents were payable for most of the pew boxes but free seating for 51 poor people was provided in the form of 17 benches in the wide centre aisle, each seating three people (see picture). None of these free standing seats survive and modern chairs, functional rather than decorative, now replace them.

The Gallery

The gallery which belonged to the School was also replaced. The new layout provided a narrow central section, where the masters sat, and two diagonal wings with rather narrow seating for the boys. Space was left behind the master' seats for an organ (which was not provided at this stage).

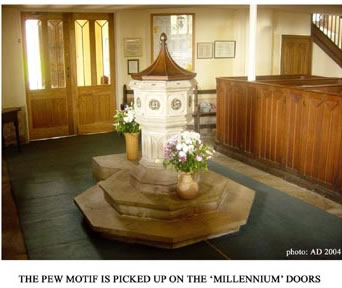

Also executed in oak, the front of the gallery copies the restrained motif of the pews below. It is fitting that this pattern has again been used on the 'Millennium Doors' inside the church entrance (see picture).

The balcony was certainly not designed to fit in with the old doorways, as the end supports would have physically obstructed them. This implies that the decision to close off the doorways was made before the gallery design was drawn up. As it is, the supports clash with the new windows. The end supports in are front of the windows and penetrate the brick filling (see pictures of closed off doorways above).

The Windows

As we have seen, new windows were inserted in the north and south facades of the building to replace the north door and south porch. It seems likely that the original tracery was faithfully copied and that this survives in all the side windows. Medieval glass was reused, especially in the heads of the north aisle windows. Eyre notes that the coloured glass in the south aisle is most probably the work of Collins of Strand, London. He comments that coloured glass of this date is unusual in Leicestershire, other known examples being at Beeby (1819) and Barkby (1828) both near Leicester (18).

The surviving records from the 1829-32 period contain a coloured drawing of a window with five lights which is almost certainly the main east window. Particular sections of the upper part of the window matrix are shown coloured as if indicating the positions of glass to be reused (19). The tracery is different from both that shown in Nichols' SE view and from the window which can be seen today. Whether or not the 1829-32 design was implemented we shall never know as it did not survive. The present east window dated 1879 is a memorial to George Moore (1811-71) and his wife Isabel (c.1811-67). The tracery may have been the work of J P St Aubyn, the architect employed in the 1870-71 remodelling of the chancel (I shall describe this final phase in the next article).

The Font

Before restoration the font had been located in the north aisle by the north door (20). It was customary for the font to be close to a doorway, where the baptised person could be symbolically welcomed into the church. Now a new font, the gift of the Misses Moore, was placed to the east end of the north aisle behind the pulpit and near the entrance to the Bosworth chapel (see plan above).

The Bosworth Chapel

The chapel itself was the responsibility of the Governors of Bosworth Grammar School, as Lords of the Manor of Appleby Magna. They complied with the wishes of the restorers and paid for the refurbishment of the chapel including the provision of seating, for their tenants and employees, along the north wall. These pews no longer exist but the wooden flooring on which they stood may be seen at the rear of the choir vestry. Part is hidden under the back of the organ.

Apart from the tomb of Sir Edmund de Appleby, which lies under the albaster effigies, the chapel contains burials of other de Applebys and some of the Dormers. No other engraved stones or plates remain visible but it is possible that some lie hidden away under the wood flooring.

The Vestry

The eastern bay of the chapel was at this time partitioned off to form a vestry for the clergy. A fireplace was installed, presumably in the corner, and an exterior door fitted under the north-facing window (21). There is no sign of the fireplace now, although the excessive amount of plastering around the external NE corner of the building may be the result of making good the wall after its removal.

The Contractors

From 1829 surviving correspondence mainly concerns the building contractor William Matthews, carpenter and joiner from Ashby, whose contract was prepared in April 1829. The correspondence which followed from time to time concerned money advanced on account and details of the building work, such as queries about the stone, window tracery and glass (22). There were also smaller additional contracts for extra work including the two new windows and the associated two new buttresses.

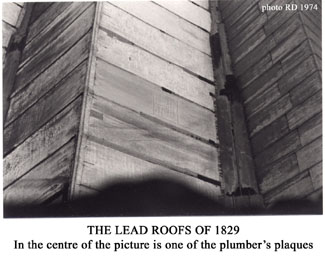

Work on the interior of the building described above was dependent upon the outside shell of the building, walls and roof, being finished and water-tight. In fact the walls and roof progressed quickly during 1829. There was discussion about using Queen slates for the inner surfaces of the main roof because it was thought that the old lead when recast might be insufficient. In the end, roofs of the main aisles were covered in lead and the chancels with Imperial slates, materials which had been used previously (23).

Payments from the Donors

The whole project which finally cost £2969-12-3 was set in motion as we have seen by the generous legacy of £1000 in 1823 from Mrs Mary Moore. William Matthews started work in April 1829 and he acknowledged receipt of a payment of £500 pounds from William Dewes the Ashby solicitor on 7th May (21) (24). The remainder of the legacy, £496-3-0, was paid on 18th September (presumably the solicitor had taken his charges). The next and second largest donation £300 came on 26 December from Valentine Green Esq. (of Normanton) co-executor and trustee with Mrs Moore of George Moore's estate (5). So by the end of 1829 almost £1300 had been donated and passed on quickly to the builder.

During the months April to August 1830 further payments were regularly received. There were three (£100, £60, £40) from Mr Blackstock, churchwarden, who was most probably gathering smaller donations from parishioners. There were three separate donations (£50, £150, £100) from 'Miss Moore', no doubt on behalf of the three sisters at the White House, and donations of £130 each from Appleby School towards their gallery, and from Bosworth School for their chapel. Payments amounting to £400 were received in 1831, £225-5-0 in 1832 and £183-8-6 in 1833. In addition to the 1832 sum there was a separate payment of £9‑17‑5 from 'Miss Moore' for the font. So by the end of 1833 the work was finished and £2874-13-11 had been received by William Matthews, leaving £94-18-4 outstanding.

Delay with the Final Payment

The death of Rector Thomas Jones in August 1830 introduced problems with the final payment. Until Rector Jones's affairs were sorted out the final bill went unpaid. On 21 January 1832 the new rector John Echalaz wrote to William Dewes about Matthews' application for the payment of his account. He agreed that Matthews should be paid quickly but 'the remaining £40 is due from the administrators of the late Rector'. That this sum was still outstanding in July is clear from Matthews' plea to Dewes: '..have you any influence with parties who are to discharge the remainder of my bill?' Clearly the answer was no because there was still no movement by May 1834. Rector Echalaz to Dewes: 'very sorry to learn that there is no legal move of raising a sum to meet Mr Matthews demand' (25). It would appear that Rector Jones was holding restoration fund money on behalf of the church at the time of his death. This was not unusual: in order to earn interest on a capital sum an investment had to be made in the name of a particular person. William Matthews received his final payment on 26th June 1835.

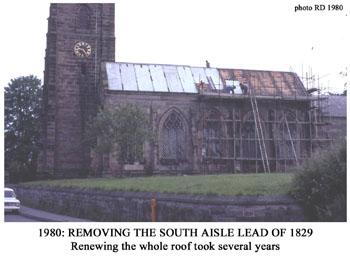

150 Years Later

The weight of large sheets of lead results in stretching and slippage, especially when subjected to a wide range of temperatures. Consequently over the years repairs were necessary. By the late 1970s it was realised that complete re-roofing was required and this was undertaken from 1980 when Canon Christopher Cox was rector. To reduce the weight of the lead sheets, narrower sections were used.

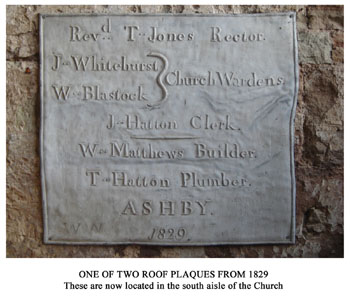

On two inner slopes of the old roof and visible only from the tower two identical lead plaques had been fixed with the names of the current rector and wardens and the clerk of the parish together with the names of William Matthews the builder and Thomas Hatton the plumber. Pigot's Directory of 1835 lists them both in Ashby de la Zouch (26). Although Matthews is described as carpenter and joiner, he was clearly more than that; he was an accomplished builder. Hatton was described as plumber and glazier.

He put the lead on the roofs and may also have been responsible for glazing the windows. By the mid-1980s, when the last of the old roof lead was taken down, Revd David Greenwood was rector. He had the plaques mounted inside the church on the east wall of the south aisle, where they may be seen. The final pictures below show the old lead roofing, before and during removal and one of the plaques.

Click images for larger views |

|

|

Notes and References

1. Aubrey Moore, A Son of the Rectory, Alan Sutton, 1982, p 22. The Hall was again much enlarged by George Moore (1811-71) in the 1830s - see In Focus 13.

2. Will of Mary Moore, 29th January 1823, Public Record Office: PROB 11/1668

3. In Focus 27: Appleby Church Restoration Part 2: A First Unsuccessful Attempt (1822-27)

4. Will of Charles Moore, 24th January 1826, PROB 11/1726 Charles Moore died at the early age of 39 from an unknown illness. In his will he left bequests to the General Infirmary and the Fever Hospital both in Leicester; and to the Magdalen Hospital in London. He also included the following instruction, perhaps indicating that the 'medical persons' were baffled: In case the Medical persons who shall see me shall consider that any use may be derived from examining my body internally it is my particular wish that they may have full permission to do so and to take away any part that they may think material to preserve.

5. Will of George Moore, 6th April 1827, PROB 11/1735; George Moore was also relatively young when he died, being only 49. In the will he also appears to have encouraged the acquisition of the church patronage or advowson: And I expressly declare that it shall be lawful for the said trustees ... to purchase any advowson or Advowsons .... In fact his son bought the advowson soon after coming of age in 1832.

6. Appleby Parish Records, at Leicestershire Record Office, Faculty 1827, 15D55/26/1

7. Appleby Parish Registers, Leics RO 15D55/4, show Mr Echalaz officiating at occasional funerals at least one month before Mr Jones's burial. The 1827 faculty names the wardens as Bateman Saddington and Thomas Whitehurst. The 1829 roof plaque has J Whitehurst and W Blastock (see last picture).

8. R J Eyre, The Nineteenth Century Restorations at St Michael and All Angels, Appleby Magna, TLAHS, LXI 1987, p 44. In writing this particular article I have drawn on and am indebted to Mr Eyre's published account of the Appleby restorations to elaborate my own rather sketchy notes. (However, he did not uncover the reasons for the failure of the first attempt at restoration described in In Focus 27).

9. Hopton Wood: British Geological Survey

10. Pigot's Directories 1835 (Leics) & 1828-29 (Derbys & Notts) list as gentry the Moores of Appleby and Snarestone, the Hurts of Alderwasley, Derbys, and the Webb Edges of Strelley, Notts, who were inter-related three ways by marriage. Some idea of the complexity of the relationships can be obtained from Mrs Mary Moore's Will, (2) above, in which many of her numerous nephews and nieces were beneficiaries.

11. David Parsons, An Emergency Excavation at Appleby Magna Church Leicestershire, TLAHS, L 1974-75, pp 41-45.

12. R J Eyre, op.cit. p 46

13. Geoffrey Brandwood, Leicestershire Churches 1825-1850 in The Adaptation of Change ed D Williams, Liecestershire Museums, 1980, p 39

14. Nicolas Pevsner, The Buildings of England, Leicestershire and Rutland p 47: 'a pair of C18 gate-piers'.

This dating must be on stylistic grounds. Were they made in 1829-32 in this earlier style or were they genuinely 18th century and imported from elsewhere? If the latter, where from?

15. No correspondence survives with either architect after 1827. It is not clear whether Mr Mason received any further payment for his work after the disputes which led to his withdrawal and that of his contractor Anthony Robinson, but Mason's drawings were certainly used (See In Focus 27).

16. Brandwood op.cit. p 46

17. J Nichols, History and Antiquities of Leicestershire, IV part 2, 1811, p 434

18. R J Eyre, op.cit. p 47. William Collins (1788-1847) maker of coloured glass, 227 Strand, London

19. Appleby Parish Records, 15D55/28/53

20. In Focus 26, see the pre-restoration plan

21. R J Eyre, op.cit. p 48

22. Appleby Parish Records, 15D55/28 and 15D55/37 contain the bulk of this material

23. R J Eyre, op.cit. p 46; 'Queen' and 'Imperial' refer to slate sizes.

24. Appleby Parish Records, 15D55/28/41: Matthews' receipt to Dewes 7th May 1829

25. Appleby Parish Records, 15D55/28/43 (21 Jan 1832); 15D55/37/1/22 (7 July 1832); 15D55/37/1/23 (19 May 1834): delays in payment of Matthews' account

26 Pigot's Directory 1835 (Leics) p 29 Ashby de la Zouch: Wm Mathews [sic] carpenter and joiner, Market Street ; Thomas Hatton plumber and glazier Kilwardby Street

©Richard Dunmore, March 2005

Previous article < Appleby's History In Focus > Next article