Appleby History > In Focus > 30 - Church & Manor Revisited

Chapter 30

Church and Manor Revisited

by Richard Dunmore

In this final article, I want to return to the origin of the village, the 'nucleated' settlement established in Saxon times. A scattering of small pre-historic farmsteads and a Roman farm had been replaced by cottages and crofts clustered around manor and church and surrounded by a developing open field system. This became the village of Appleby Magna which we know today.

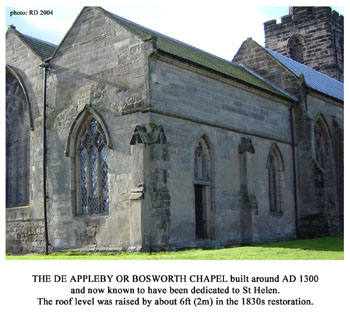

Evidence for the church having its origins in this early period lies in the chapel located in the north-east corner of the building and now used as the organ chamber and vestry. This chapel was the preserve of the lords of Appleby Magna manor and its names reflect this. So it was known as the de Appleby Chapel after the medieval lords of that name; and the Bosworth Chapel in the post Reformation period when the governors of Bosworth School held the lordship.

The position of the chapel within the churchyard, together with its shape and dimensions, suggests that it may occupy the footprint of a Saxon church and even retain some original material within the footings and lower structure (1).

Click for larger view |

The dedication name for the chapel did not survive the church restorations of 1829-32 and 1870-72 when the chapel was downgraded to vestries and organ chamber. The chapel ceased to be used for its original purpose and its dedication was simply forgotten.

St Helen

There is however a clue to its original appellation in the survival of the saint's name St Helen attached to two local sites very close to the church and manor. The footbridge over the brook on the Hall Yard footpath and the field now occupied by the lower part of Garton Close both carried her name (2). Rental of St Helens close (the field) may have provided income for the maintenance of a chapel. There are two possible candidates for a consecrated building dedicated to St Helen: a private chapel situated within the manor compound, ie on the Moat House site; or the de Appleby chapel itself, in the parish church (3).

The de Applebys

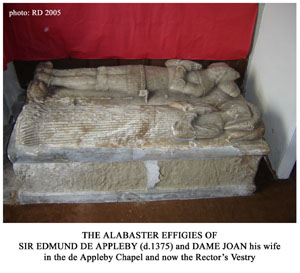

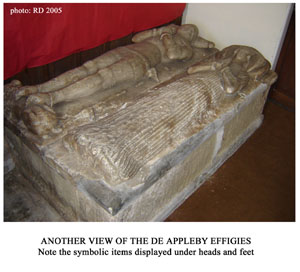

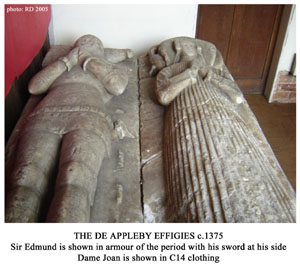

From the year AD 1166, 100 years after the Norman Conquest, until the mid-16th century Appleby Magna manor, whose remnant is the Moat House, was held by the de Appleby family who took their name from the village. Within the de Appleby chapel, under the alabaster effigies, lies the tomb of the family's most famous member Sir Edmund de Appleby, who died in 1375, and his wife Dame Joan. However, many other members of the family are buried in the chapel too, although their graves are no longer marked (4).

|

|

|

The church was built in the mid-14th century during Sir Edmund's lifetime. Differences in architectural style indicate that the chapel was built maybe as early as AD 1300 and before the early to mid-14th century main body of the church was constructed (5) (6). So the main body of the building was constructed around the south and west sides of the somewhat older chapel. Use of the chapel as a burial chamber and private chantry chapel throughout the de Appleby family's tenure of the manor shows that it was valued and conserved as a place hallowed by their ancestors.

When Sir Edmund de Appleby died in 1375 he left an inventory of his belongings, the details of which were preserved by John Nichols. Sir Edmund's possessions are listed room by room in the manor house and its associated buildings. Of particular interest here is the section dealing with the Lord's Chapel. The chapel contained an altar, vestments, a chalice and an altar book but the location of the chapel itself was not given (7). I suggested in a previous article that, rather than referring to a chapel in the manor buildings, the inventory was describing the contents of the de Appleby Chapel in the church. This was only a short walk away from the manor house and was where Sir Edmund himself was buried (8).

It has now become clear that this indeed was the case and that the de Appleby Chapel was dedicated to St Helen. The conclusive information comes from the will of Edmund Appleby, Sir Edmund de Appleby's four-times-great grandson, who died in 1506.

The Will of Edmund Appleby of 1506

The instructions contained in the last will and testament of Edmund Appleby, which was made on January 10th and proved on January 31st 1506 (1505 old style calendar), gave particular instructions concerning his burial (9).

The medieval Latin [expanded here in brackets from its abbreviated original] reads:

Corpore[m] que meu[m] ad sepeliend[um] in Capella mea S[anc]te Helene in Appulby predict[a] cum ancestoribus mei[us]

which translates as:

and my body to be buried in my Chapel of St Helen in Appleby aforesaid with my ancestors.

The Chapel of St Helen

There are three points to note here: Edmund says that it is my Chapel, ie mine as lord of the manor; the Chapel is of St Helen in Appleby; and my body is to be buried with my ancestors.

Nichols in writing about Appleby Church tells us of the memorial inscriptions to members of the de Appleby family at that time (1811) still to be seen in the chapel. This was where Sir Edmund was buried in 1375 and which was referred to in his inventory as the Lord's Chapel. There can be no doubt therefore that this is the chapel of Edmund's ancestors, referred to in Sir Edmund de Appleby's inventory of 1375 and dedicated to St Helen as stated in Edmund Appleby's will of 1506.

There are a number of other features of the will which are of interest and typical of the medieval Catholic period; and others of particular local interest regarding the de Appleby family and the Moat House. My translation of the complete will is given in the Appendix.

Catholic Beliefs

Typical of the period, the whole will is couched in religious terms:

In the name of God Amen ...

I bequeath and commend my soul to Almighty God my Creator and Saviour and the Blessed Virgin his mother and all Saints and my body to be buried in my Chapel of St Helen ...

Pious Bequests

There follows a list of monetary bequests to local churches, a particular payment for thirty masses 'for my soul' - presumably in St Helens Chapel in its capacity as a chantry chapel, and donations to the friars at several monasteries in the Midlands and to a hermit and two anchoresses well-known in the district. It may be surprising to us that there should be such concern for the wider church in a relatively obscure village on the Derbyshire - Leicestershire border. At least part of the explanation for this must lie in the fact that the Derbyshire part of Appleby Magna continued to be held by Burton Abbey until its dissolution in 1539 .

As well as Appleby Church itself, the other parish churches receiving bequests lie on an arc around the parish: Netherseal, Stretton, Measham, Snarestone, Norton and Austrey. The local religious houses which benefited were the small priory ('abbey') at Gresley, the priories at Coventry and Lichfield and the abbeys at Burton and Leicester. The friars were to offer masses for Edmund's soul. Appleby had connections with Coventry, as well as Burton, from Countess Godiva's ownership of the manor at Appleby Magna in pre-Conquest Saxon times (10).

Perhaps strangest of all to our modern ideas is the existence of a hermit and anchoresses (female hermits) at Lichfield and Polesworth who were clearly held in high regard. The anchoress at Polesworth received twice as much as both the hermit at Polesworth and the anchoress at Lichfield.

The amount donated to the poor results from some curious arithmetic (15 = 3 + 12): '15s to the poor for my soul i.e. 3s in the name of the Trinity and 12s in the name of the Twelve Apostles'.

The monetary amounts may also appear to be odd until it is realised that most of the bequested sums are fractions of the mark. This was a currency unit used across medieval Europe (rather like the modern euro) and was valued at two-thirds of a pound, ie 13s 4d. So 6s 8d was half a mark, 3s 4d one quarter mark and 20d one eighth. The fact that there was no English mark coin was irrelevant.

Personal Bequests to Brother and Sister

Nichols' pedigree of the de Applebys cites the date of Edmund's will and shows his siblings: one brother Richard Appleby and one sister Margaret Appleby. Edmund had a son, also Richard, but Edmund's will benefits Richard his brother (frater). It may have been considered that young Richard was already well provided for as he was co-heir to Richard Peshall, his 'cousin-german' (ie first cousin) on his mother's side of the family, his father having married Joan Peshall.

In the 1506 will the two family beneficiaries, and joint executors, are named as Richard my brother and Margery, who is described variously as widow and Edmund's sister, but is clearly the same person. Nichols' use of the name Margaret appears to be a mistake (11).

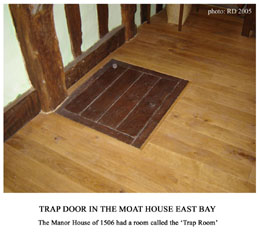

From Edmund's will, his brother Richard inherited the best feather-bed and Margery the 'other' one. Richard also received the valuable farm items: eight oxen, five horses and two ploughs. Mindful that she was a widow, special provision had already been made ('I have given ... by my deed') for Margery's maintenance by regular annual (or biannual) payments of 20s - ie one pound per annum. Edmund had also allocated accommodation for her in the form of a chamber or room called the Trap Room (12). If he so wishes Richard is invited to continue this support for his sister.

But where exactly was 'unam cam[er]am vocatam Le Trap Chambre' - a room called the Trap Room? We can only surmise that it was an upper chamber in the Manor House of a reasonable size and in which a widow could live comfortably. It was distinguished by its trap door, although that would certainly not have been the only means of access.

The Moat House and the early Manor

What, if any, is the relationship between the Moat House we see today and the manor occupied by the de Appleby family in the 14th and 15th centuries? Some of the evidence has only recently come to light. In addition to Sir Edmund de Appleby's inventory of 1375, we now have the documentary evidence of Edmund Appleby's will of 1506 described above.

Until recently the physical evidence has consisted of the structure of the building itself with its setting within the moated compound. Now, we also have tree-ring analysis from timbers in both bays of the building to provide dates for the two principal phases of its construction.

Documentary Evidence

Sir Edmund de Appleby's Estate of 1375

The house whose contents are described in Sir Edmund de Appleby's inventory of 1375 was quite simple, lacking private space for the occupants. There was a single chamber for the lord and his family. This was almost certainly above the hall which was used by the lord as a court and for estate business. The hall also provided the servants with a place to sleep. In addition there were the utility rooms of pantry and buttery, kitchen, larder and bakehouse. The chamber contained seven beds and four chests so it was a sizeable room. In the hall was a chimney which, because it was listed amongst the valued items, Hoskins deduced to be a 'piece of portable property' (13). So there was no permanent chimney stack at this date and the hearth would have been in the centre of the hall.

However, many of the furnishings and possessions were quite luxurious, including colourful embroidered fabrics and pieces of silver and silver-gilt. The farm buildings also were well equipped. There were two stables, one of which was for the lord's four personal horses and another for five working horses. In the farm buildings were 12 oxen with nine ploughs, two bulls, 19 cows, 10 younger steers, five calves and another six oxen 'for the plough'. Sir Edmund also had a flock of 88 sheep. If the house stood in a moated enclosure at this early date, the farm buildings and stock must have been outside it because of the limitations of size and access imposed by the moat.

So this inventory tells us that the house in 1375 had a simple structure, typical of its time, and that the lord of the manor, Sir Edmund, was a relatively wealthy man as befitted a knight in the King's service. This was clearly a prosperous working farm (14).

Edmund Appleby's Estate of 1506

By contrast the 1506 will of Edmund Appleby reveals a much less prosperous man (see the Appendix). The key items specifically detailed, and bequeathed to his brother Richard and sister Margery, are the two feather beds and the essential farm animals and equipment - 8 oxen with a plough and 5 horses with another plough. Everything else comes under the cover-all expression 'the remainder of my effects' which he also gave to Richard and Margery, his only siblings. The fact that the oxen, horses and ploughs were picked out for specific mention must indicate that they were the principal effects of the farm and that there was little else of particular value to bequeath.

Although, after Sir Edmund, the Appleby family produced several more knights of the realm serving the king of the day, by the 16th century, their fortunes were apparently waning (11). Finally in 1549 Edmund's great-grandson George sold the estate (15). The existence of the Trap Room in 1506 shows that the manor house had already been divided into smaller rooms but it seems unlikely that sufficient wealth had been generated to enable any of these manorial lords to build a grander house on the site. That the farm business was much less prosperous by 1506 is perhaps an indicator of the general economic climate of the 15th century.

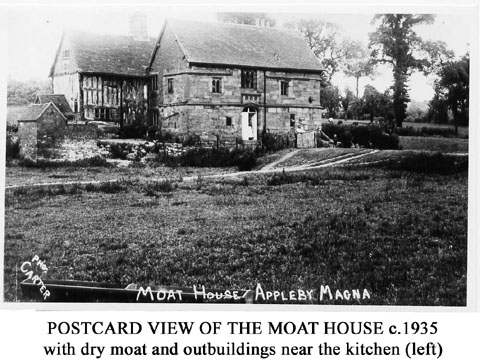

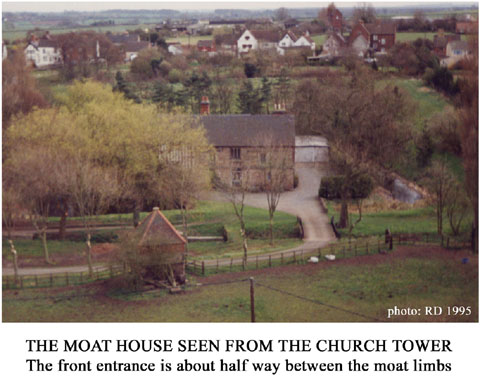

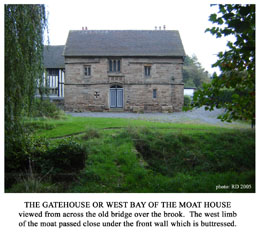

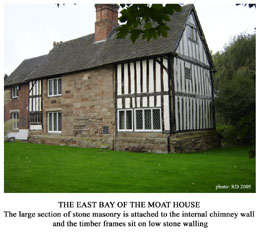

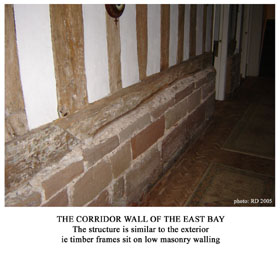

The Physical Evidence

The Moat House is a composite structure. There are two principal bays comprising a substantial front (west) bay built of stone which is referred to as the 'gatehouse'; and a rear (east) bay which is timber-framed and stands on a plinth of low masonry walling. The gatehouse was built more or less centrally against the inner edge of the west limb (now filled in) of the moat. The east bay projects some twenty feet north of the west bay and therefore does not lie symmetrically, either in relation to the west bay or within the moated compound. These two very different structures have been joined by enclosing the passageway between them to form internal corridors on two levels.

|

|

Click images for larger views |

|

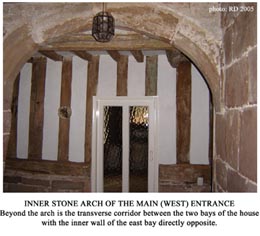

The entrance passage through the gatehouse is five feet wide and would have permitted the entry of people on foot, or horse riders in single file when there was an open exit to the rear.

Click for larger view Click for larger view |

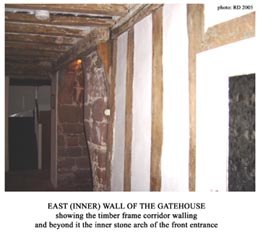

The front door now occupies the Tudor archway. The surprisingly narrow entrance may reflect the seriousness of the threats which the building's defences were designed to repel when it was constructed.

The corresponding stone archway at the rear of the entrance passage now leads into the transverse internal corridor which runs between the two bays. The east bay was built projecting across this rear exit, separated by only the width of the corridor. From the time that this was done, taking a horse through the gatehouse into the moated compound would have been no longer practicable (see photographs below). The gateway therefore appears to have been constructed first and the east bay built when the gatehouse was no longer required to control access to the moated enclosure.

|

|

Click images for larger views |

|

In the 19th century the east bay was extended southwards using brick to bring it level with the south end of the stone gatehouse. The roof of the whole assemblage is tiled with slates forming two roofs.

Comments of an Architectural Expert: Nikolaus Pevsner

Pevsner's interpretation of the building is as follows.

'Of the C15 house the GATEHOUSE survives (rebuilt, according to Mr M W Barley). Gateway to the W centrally in the stone wall. The corresponding E arch is now inside the house. Row of quatrefoils above the gateway. Windows relatively symmetrically arranged, small, of two lights, with different tracery details. The house itself does not survive. Instead there is, attached to the E wall of the gatehouse, a timber-framed house, according to its closely set uprights not later than the late C16.' (5)

The entrance doorway (Pevsner's 'gateway') is in fact not central in the west-facing stone wall but displaced to the north (left) by half its width (see West Bay photograph above). The upper windows are more or less symmetrical in relation to the entrance. To the right of the entrance the stonework shows signs of reconstruction and possibly extension by about 5ft. Before such alterations, the frontage would indeed have been symmetrical. The stone moulding below the roof line of the west front suggests that there was formerly a central turret or tower above the entrance. This confirms the defensive purpose of the structure (16).

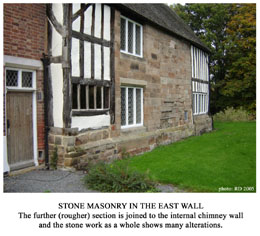

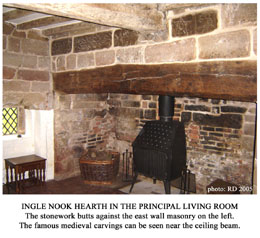

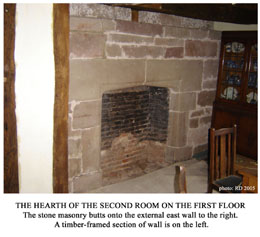

Pevsner's brief account omits to mention that the east bay is not wholly timber-framed. There is a complex stone section in the middle of the east wall from which projects a massive stone internal structure incorporating a chimney stack. This serves back-to-back fireplaces on the ground and first floors, which are thus divided into separate rooms. The east wall masonry itself has had two or three stages of construction or alteration and the stone plinth on which the walls of the east bay rest is altered under the stone section (see photographs below).

|

|

|

|

The principal downstairs room in the timber-framed bay, with the massive ingle-nook hearth shown in the picture, was a kitchen in Victorian times. There was an outhouse attached to this room at the north end in the mid-1930s. This can be seen in the 1935 postcard photograph shown above. The rougher column of stonework on the east wall, visible in the outside photographs of the east bay, may have resulted from the removal of the kitchen oven chimney. Its probable location was in the niche seen to the left (now with a small window) in the picture of the ingle-nook hearth. To the left of that again, and now replaced by a section of window frame, was the kitchen door with porch (17). Curiously this room has a trap-door in its ceiling opening to the principal bedroom (see picture).

A Defensive Shell of Stone Walling

The most surprising thing about the gatehouse is that the inner wall facing the corridor is not built of stone. Apart from the inner arch of the entrance passageway, the wall is timber-framed (see corridor picture above). The main fortified structure of the gatehouse can therefore be seen to be a massive shell of stone walling comprising the west front, flanking side walls and the entrance passage walls. The rest of the structure consists of timber-framed walling.

Tree-ring Analysis

In 1998 seven samples of timbers from the Moat House were taken for dating analysis by the Nottingham University Tree-ring Dating Laboratory (18). All were taken from roof or ceiling joists, timbers which would therefore have been used in the later stages of building or reconstruction.

Patterns of variation of the widths of tree-rings are known as chronologies. These depend on the seasonal changes in tree-growth from year to year. The sampled tree-ring growth patterns are compared with known tree-ring sequences called 'reference chronologies'. To enhance the accuracy of the analysis for any particular building, samples with closely similar patterns are grouped together to form 'site chronologies' before comparison with the references. There may well be several different such chronologies in a building which has been altered and these enable dates to be allocated to each phase of building.

The Moat House samples formed two distinct groups (the site chronologies). Three samples from transverse tie-beams in the roof of the east bay together with one longitudinal bridging beam from the gatehouse (west bay) formed the first group, with a felling date for the timbers between the summer of 1621 and the spring of 1622.

The second group of samples were all taken from ceiling joists in the gatehouse. Although there was less precision (due to the relatively short sequence of tree-rings available) the estimated felling date for this group was within the year range 1509 to 1534. The word felling is emphasised because felled timber was not necessarily used immediately for building. However, stockpiling of felled timber was unlikely to be for more than a few years and is not important for our purposes.

The two date periods arising from the tree-ring analysis confirm the visual assessment that the timber-framed east bay was built after the stone gatehouse. The construction of the gatehouse took place in the first half of the 16th century ie during the reign of Henry VIII (1509-47). The Tudor features of the stonework agree well with this. The east bay was added in 1621-22, in the reign of James I (1603-25). A single house was formed by constructing the east bay as an extension (in modern parlance) to the gatehouse, at the same time as modifying the gatehouse itself and thus forming a new composite dwelling. At this point the archway through the gatehouse was abandoned as an entrance to the moated compound.

Who first built the defensive Gatehouse? The de Applebys

With definite dates to work with, we can now consider who constructed the two bays of the building. As we have seen the Appleby family owned the manor until 1549 when it was sold by George Appleby so it must have been one of the Applebys who built the gatehouse, maybe as the first stage of a fortified manor house.

Edmund Appleby had died in 1506, so possible candidates as builders of the gatehouse are his brother Richard who inherited from Edmund's will; his son Richard who died in 1527; his grandson George, born 1513 and 'slain' in battle at Musselborough field in 1547; and finally great-grandson George who sold the estate in 1549, was still alive in 1561 but later drowned (11). It is not possible to say which of these was responsible, although the soldier George who died in battle would have been aware of the necessity for good defences at home.

Who turned it into the Moat House? The Dixies of Bosworth

The tree-ring dates for the timber-framed east bay are very precise (summer 1621 to spring 1622). The longitudinal beam from the gatehouse is included in this chronological group, implying that the gatehouse was adapted at the same time as the east wing was built.

After the sale by George Appleby in 1549 the manor changed hands several times until, in 1605, the manor lands were purchased by John Dixie and his son Sir Wolstan Dixie to endow their Grammar School at Market Bosworth (19). Sir Wolstan himself may have lived briefly at Appleby. His younger brother Richard, with his wife Bridget, definitely did do so. Their presence in Appleby is confirmed by the fact that the Appleby registers record their burials: Bridget in 1625 and Richard in 1627. They were probably buried in the parish church in the chapel of St Helen.

So it appears that the house was reconstructed for Richard and Bridget Dixie's use. Their son John was baptised at Appleby church on 15th January 1623 (modern calendar) whereas an elder son Richard was not (20). The implication of this is that they moved in when the house was ready (not before 1622) but before John's baptism early in 1623. The adapted house must have been ready for Richard and Bridget by the end of 1622. Sadly they did not enjoy it long and, of their three sons, two died unmarried and the third, 'Wolstan Dixie of Appleby, Farmer' died without issue (21) (22).

Some Conclusions

The 1506 will of Edmund Appleby has revealed St Helen as the dedication saint of the former de Appleby Chapel in Appleby parish church. It has also shown the declining prosperity of the family from the days of Sir Edmund de Appleby in the fourteenth century to when they finally sold up in 1549. It has also given a tantalising piece of information about the Manor house - that it had a 'Trap Room', interpreted as a room with a trap-door.

Physical analysis of the Moat House shows it to have been built in two periods, both of them later than the two Edmunds. Until recently, architectural style has been the principal means of dating, with the stone gatehouse said to be 'Tudor' and the timber-frame section 'not later than the late 16th century' (Pevsner). Tree-ring dating has now enabled more precise dates to be allocated.

The stone gatehouse is indeed Tudor. The tree-ring samples show that it was built within +/-15 years of 1525, in the reign of King Henry VIII (1509-47). The tenants at this time were the (de) Appleby family, descendants of Sir Edmund of the 14th century. Importantly, we can say that it was built after the time of Edmund Appleby whose will was discussed above.

The timber framed east bay was built as an extension to the gatehouse, the combination forming a new dwelling in 1622, ie about 100 years later and in the reign of King James I (1603-25). The precision of this dating arises from the accuracy of the tree-ring analysis and knowledge of the activities of the Dixie family from Bosworth who had purchased the manor about 1605. That the defensive use of the gatehouse was apparently abandoned at this time is an indication that the country was more stable in early Stuart times (the Civil War was yet to come). It is possible that stone was robbed from the back of the gatehouse to build the chimney wall, leaving the shell of stone on the west front.

The manor inhabited by Edmund Appleby in 1506 (with its Trap room) was in all probability the same building as that of his forebear, Sir Edmund de Appleby, in the 14th century. The time scale and the apparently dwindling fortunes of the family make it unlikely that a new house was built in this period and in any case a new building (the gatehouse) was erected only 20 or so years later.

The Tudor gatehouse seems to have been the first stage of a new fortified manor house which was never completed. George Appleby's death at Musselborough may have put paid to any further building work. Nevertheless the gatehouse would have performed a defensive role for the old manor until the Dixies remodeled it to form the Moat House. The shell-like structure of the stone sections of the gatehouse bay points to the possible re-use of stone for the chimney wall.

Where was the old manor house located in the moated compound? We can be certain that it was not as close to the gatehouse as is the east bay of the present house, which blocks off the old entrance passageway. It may not however have been far away. It is tempting to think that the trapdoor of the Moat House east bay shows some continuity from the earlier house, which also had a trapdoor, but that would be speculation.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Jon and Marilyn Dunkelman for allowing me access to the Moat House, for the information on tree-ring dating and for permission to take photographs. Thanks also go to Richard Johnstone, the previous occupant, for whom the tree-ring analysis was carried out.

Notes and References

1. In Focus 6 and 7 (de Appleby Chapel and a possible Saxon church)

2. In Focus 6 (St Helens close and bridge)

3. David Farmer, Oxford Dictionary of Saints, OUP, 1997 (Helen). The dedication of churches to St Helen was popular from Saxon times. Helen (c. AD 250-330) was the mother of the Roman Emperor Constantine. Her conversion to Christianity and the influence of this on her son had a huge impact on Western Christendom. Constantine adopted Christianity as the official religion of his empire which became known as the Holy Roman Empire.

4. Nichols, op cit: p 428 (1166 William de Appleby; family tombs ); p 436 (family monuments)

5. Nikolaus Pevsner, The Buildings of England, Leics, Penguin, 1960/1977, p.47, gives a date for the chapel by implication - 'nothing earlier than c.1300'. Both the windows and the arcade (arches) of the chapel are stylistically earlier than those of the main building. Also p 48 the manor house.

6. Leonard Cantor, The Historic Parish Churches of Leicestershire and Rutland, Kairos Press, 2000, p 23: the curvilinear tracery of the Decorated Gothic windows puts the date of the main building late in the period 1280-1350

7. Nichols op cit, p 429 (Sir Edmund de Appleby's 1375 inventory, in Latin - see also In Focus 7)

8. In Focus 7 (the lord of the manor's chapel)

9. Will of Edmund Appulby, Public Record Office, PROB 11/15, 10th January 1505/06

10. In Focus 4 (pre-Conquest connections with Countess Godiva and Burton Abbey)

11. Nichols op cit, p 442 (Appleby pedigree); Nichols' erroneous name Margaret may be due to mistranslation of Margeria,-e (f.) Margery, from Latin. Also p 442 (de Appleby knights).

12. The past tense 'dedi Margerie ... per cartam meam' meaning 'I have given Margery ... by my deed', suggests that she was already legally provided for. Edmund's wife Joan does not appear in the will, so it seems probable that he too was widowed and Margery kept house for her brother.

13. W G Hoskins, Midland England, Batsford, London, 1949, p 45 ('portable' chimney)

14. In Focus 7 (Sir Edmund de Appleby's belongings)

15. Nichols op cit, p 430 (manor 'alienated' or sold by George Appleby in 1549)

16. Nichols op cit, p 431: 'It had only one entrance (over which was antiently a tower), ...'.

17. James Thompson, A Medieval Manor House, The Midland Counties Historical Collector, Vol 1, No 4, 1 Nov 1854, p 52 (kitchen, and porch to its door-way, opening on the area behind).

18. R E Howard. R R Laxton, C D Litton, Tree-ring Analysis of Timbers from the Moat House, Appleby Magna, Leicestershire, Nottingham University Tree-ring Dating Laboratory, 1998

19. Peter Foss, The History of Market Bosworth, Sycamore, 1983, p 50; the Dixies purchased two estates at Appleby Magna: the manor and (probably) the former estate of Burton Abbey.

20. The baptism of John and the burials of Bridget and Richard are the only Dixie entries in the Appleby parish registers. Of Richard and Bridget's three children, Richard, John (bap.1622) and Wolstan ('of Appleby'), the two younger ones were probably born in Appleby.

21. Nichols op cit, p. 506, (Dixie pedigree). The last Dixie connected with Appleby is 'Wolstan Dixie of Appleby, born 1631'. This Wolstan, Sir Wolstan's grandson, was 'living unmarried 1683'.

22. On August 17th 1628, the baptism of 'Woollston son of Thomas & Joyce Tabernor' is recorded in the Appleby parish register. He was buried at Appleby on 1 June 1685. The Taverners (spellings vary) held the tenancy of the manor until the late 19th century, from perhaps as early as the late C17th. Their long tenancy of the Moat House is recorded by Nichols (1811) - 'the present occupiers ... have lived therein more than half a century' (p.431) - and in all the C19th trade directories up to 1877. The name Wolstan is of course usually associated with the Dixies. Wolstan Taverner (1628-85) was a near contemporary of Wolstan Dixie 'of Appleby' (born 1631, see 21. above) whose father Wolstan Dixie (1602-1682) (later Sir Wolstan Dixie, bart.) may well have lived for a while at Appleby following the death of his uncle Richard Dixie in 1627.

©Richard Dunmore, January 2006

APPENDIX

WILL OF EDMUND APPLEBY 1506

In the name of God Amen I Edmund Appleby of Appleby in the County of Leicester gentleman acknowledged as being in sound mind and health

the 10th January AD 1505† and the 21st year of King Henry Seventh commit make and appoint my testament in this manner

Firstly I bequeath and commend my soul to Almighty God my Creator and Saviour and the Blessed Virgin Mary his mother and all Saints and my body to be buried in my Chapel of St Helen in Appleby aforesaid with my ancestors

Firstly I bequeath to Appleby Church 6s 8d

Item I bequeath Gresley Abbey estate 3s 4d

Item to [Nether]seale church 20d ... to Stretton Church 20d ... to Measham Church 20d ...

to Snarestone Church 20d ... to Norton Church 20d ... to Austrey Church 20d

Item 20s payment for thirty masses for my soul

Item to the Friars of Coventry 3s 4d ... to the Friars of Lichfield 3s 4d ...

to the Friars of Leicester 3s 4d ... to the Friars of Andressey‡ [Burton Abbey] 3s 4d

for saying prayers and masses for my soul

Item to the Anchoress of Lichfield 20d ... to the Anchoress of Polesworth 3s 4d

Item I give 15s to the poor for my soul

i.e. 3s in the name of the Trinity and 12s in the name of the Twelve Apostles

Item to the Hermit of Polesworth 20d

Item I have given to my sister Margery 20s per annum by my deed

Item I have given her a room called the Trap Room for her lifetime

Item if Richard Appleby brother and heir of Edmund wishes, to give to the widow Margery during her lifetime part payments both at Lent and annually as stated [above]

The same [Richard] is to have the best feather-bed and the accessories belonging to it

Moreover he is to have eight oxen with a farm plough

also he is to have five horses with a farm plough

Item I give to the said Margery the other feather-bed

However the remainder of my effects not [already] bequeathed I give to Richard my brother and heir and to Margery my sister whom I confirm and make my true executors in order that they distribute them for the salvation of my soul .

They are by these [deeds] able to answer promptly before the justices.

Probate

The above written will was proved before the lord at Lambeth on the last day of January AD 1505† on the oath of Richard Appleby, present in person, and the widow Margery, executors named in this will.

In person Richard Gifford, proctor* himself in this regard &c, approves, gives countenance to and has entrusted the administration of the goods and acknowledged debts of the said deceased, to the executors

for well and faithfully administering, and by full and faithful rights before the feast of St David, shown in fact promptly and truly by accounts rendered to the immediately next assembled jury.

[ †1506 modern calendar; ‡Andressey, literally 'Andrew's Isle', an island in the river behind the parish church at Burton upon Trent; *the proctor was an official in the ecclesiastical courts of probate ]

Previous article < Appleby's History In Focus > Next article