Appleby History > In Focus > 32 - Sir John Moore's Benevolence 2

Chapter 32

Sir John Moore's Benevolence

Part 2 - The Lancashire Connection

by Richard Dunmore

In which we discover Sir John Moore's family link with the debt-ridden, anti-royalist Mores of Bank Hall and how their estates were sold at long last to redeem Sir John's generous mortgage loan to them. Consequently, the Moores of Appleby were made to wait 23 years after Sir John's death before receiving any of his wealth.

The revelation in the last will and testament of Sir John Moore, 1702, that he was owed the sum of £13,000, 'due from and charged upon the Estate of Sir Cleave Moore', was a complete surprise. Until I examined the wills of the Appleby Moores, I had found no hint of Sir Cleave Moore's existence, let alone of financial dealings with him. Sir John Moore's will itself is not forthcoming about the identity of Sir Cleave Moore. All the recognised family members mentioned are given a brief description, at the very least 'cousin' to imply a definite, but perhaps distant, family relationship, but for Sir Cleave Moore there is nothing, no relationship and no information concerning the whereabouts of his estate.

The sum involved was large and is equivalent to about £1.90 million pounds in today's values, which makes the mortgage all the more surprising. By Sir John's will, this large debt was passed on to the next generation and John Moore of Kentwell Hall as Sir John's executor and heir had to take it on. It is from John's own will of 1714 that we begin to get details of the location of Sir Cleave Moore's estate. He refers to 'the Manor or Manors ... of Sir Cleave Moore Baronet Situate lying and being in the County of Lancaster and which are in Mortgage to me or were in Mortgage to Sir John Moore Knt late Alderman of the City of London Deceased '. Sir Cleave 'Moore' must have been one of the Lancashire 'More' family mentioned by Nichols in connection with the origins of the Appleby Moores:

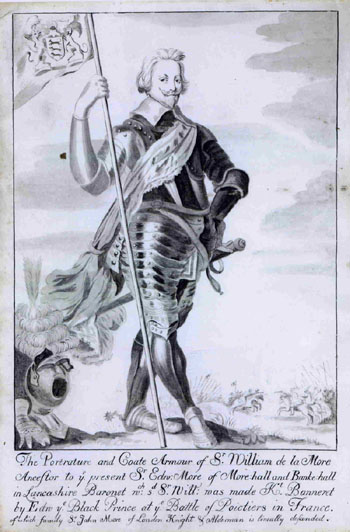

'Among the ancestors of the Moores may be honourably mentioned sir William de la More (from whom likewise are descended the Mores of More hall and Bank hall in Lancashire), who was advanced to the rank of a knight banneret by Edward the Black Prince, for his eminent services done at the battle of Poictiers in France' (1). This statement, as we shall see, is an adapted quotation from the inscription attached to a 'portrature' of Sir William de la More still in the possession of the Appleby Moore family. This depiction of Sir William de la More will be discussed below.

Finding Sir Cleave Moore (or More) and his connection with the Appleby Moores therefore required knowledge of the line of descent of the Mores of Lancashire. The use of 'More' rather than 'Moore' seems to have persisted in Lancashire, where the family originated and where southern ways were slow to take root. By 1600, perhaps earlier, the link 'de la' was also being discarded, so the name gradually mutated from 'de la More' to 'More' and eventually to 'Moore'.

The Lancashire Mores

The increasing availability of historical material on line is proving invaluable. Details of the Mores of Bank Hall are given in Parts 3 and 4 of the Victoria County History of Lancashire (VCH) (2) (3). Bank Hall was in the parish of Kirkdale in what is now part of Liverpool. There is now also on line a profile of Sir Cleave More as a member of the House of Commons (4).

The earliest record of the family is of Randle (or Ranulf) de la More, reeve of Liverpool, who appeared at the Lancaster session of justices in 1246 (5). Such incidental dates are also given for succeeding generations, there being few direct records of birth and deaths at this early stage. Nevertheless, this limited dating information is sufficient to allow construction of a basic line of descent. My attempt at this from 1246 to about the year 1600 is shown in CHART 1. The result is not a perfect family tree in the usual sense because of the scarcity of dates, but it does give an impression of how the family developed from those early years.

CHART 1: MORE OF BANK HALL TO c.1600

(pdf file, opens in separate window - requires Acrobat Reader)

Surprisingly there are no details of Sir William de la More, let alone the circumstances of his knighthood, in the VCH accounts, but there is a William described with sufficient date detail to identify him. More information concerning his years come from the National Portrait Gallery, of which more below. The site of Bank Hall, which became the family seat, is first identified from a Kirkdale charter of 1417. The last name on CHART 1 is William More (1538-1602) and the settlement of this William's estate in 1599 provides the vital clue from which the link between the Bank Hall and Appleby families may be deduced.

The Crucial Year of 1599

The usual enquiry after the death of a propertied man, the 'Inquisition post mortem', was held in 1604, two years after William More's death. The enquiry established that in 1599 he had settled his manors including Kirkdale and Bootle on Edward and Richard More, sons by his second wife. His eldest son John was passed over because William regarded him as an 'unthrift', ie a prodigal or squanderer. Amongst other things John had prematurely sold some of his father's property without permission. Unfortunately for him too, he had only daughters whereas, also in 1599, William's second son Edward became the father of a son, another John. This perpetuation of the male line may have decided the timing of the settlement. In September 1602, the year of their father's death, Richard, the younger son, released all interest in Kirkdale and Bootle to Edward who thus acquired complete ownership of the estates (2). The wayward John died in 1604, reputedly in prison, at the age of 38 years.

The year 1599 was a landmark date for the Appleby Moores too when Charles Moore Sen. of Stretton en le Field purchased the manor of Appleby Parva, thus becoming Lord of the manor (6). Given the claimed link between the two families, is it possible that the purchase of Appleby Parva manor and the settlement of William More's estates in Lancashire in the same year were connected? As noted above, the Appleby Moore family, Sir John in particular, claimed direct descent from the Lancashire Mores. Could it be that the first Charles Moore of Appleby Parva was also a son of William, younger than Edward and Richard? If that was the case, he might be expected to have received a share of his father's estate in 1599, thus enabling him to purchase the manor. As Charles was apparently already at Stretton en le Field, it would be natural for him to want to purchase the adjacent manor to increase and consolidate his land holding (7).

CHART 2: MORE / MOORE FAMILY TREE FROM c.1600

(pdf file, opens in separate window - requires Acrobat Reader)

To test this idea I have put together in CHART 2 the Lancashire and Appleby lines linking Charles Moore Sen. as a younger son of William More (1538-1602). For this to be plausible, the supposed birth year of Charles would have to be compatible with those of William's sons. Additionally, the revealed relationships between Sir John Moore and Sir Cleave More and his predecessors, might produce confirmatory evidence for the link. The family 'portrature' of Sir William de la More with its inscription also has vital clues. The Lancashire line is taken from the Kirkdale entry in VCH 3 (2).

The Lancashire Mores from c.1600

Edward More who inherited the More Liverpool estates in 1599 was notable for his zeal against recusants. He seems to have made up for his being the only Protestant gentleman in the area by his particularly keen pursuit and persecution of Catholics. Paradoxically he married the daughter of a convicted recusant. He was sheriff of Lancashire in 1617 and MP in 1625. His sudden death in 1632 was naturally regarded by the Catholics as divine judgement - and greeted with much relief.

His son (Colonel) John Moore (8), born in 1599, continued the strong Protestant tradition and was an active supporter of Cromwell during the Civil War. He had been mayor of Liverpool in 1633, served as MP for Liverpool in the Long Parliament and, in the build up to civil war, organised Parliamentary resistance in Lancashire. He assumed a prominent role in London as colonel of the militia guarding Westminster and the City of London. Appointed governor of Liverpool in 1643, he defended the city for five days against attack by Prince Rupert in 1644, before escaping by sea. This episode led to accusations of desertion. He resigned the governorship and all military commissions the following year under the Self Denying Ordinance, by which all officers were required to resign and be reappointed (or not) by Cromwell. He devoted himself subsequently to parliamentary committee work.

Later, Colonel Moore was appointed to the High Court of Justice and organised security arrangements for the King's trial in 1649. He attended the trial and was one of the 49 'regicides' who signed the death warrant of King Charles I (9). His last years were spent in Ireland, where he had been appointed Governor of Dublin, and he died there of a fever in 1650. As MP for Liverpool from 1640 until his death, he is credited with being a man of letters as the Parliamentary diarist of that period.

(Sir) Edward More (1634-78) inherited the Lancashire estates in 1650 on the death of his father, Colonel John Moore. He is said to have been embarrassed by his father's debts. This would seem to put it mildly. One report suggests that Colonel Moore had accumulated debts by his exertions for Parliament which amounted to £10,000 by the time of his death (4). But the fact that he was a regicide would itself have had extremely serious consequences for his successor. At the Restoration of King Charles II in 1660, all the regicides were hunted down and severely punished, ten of them by public execution. Those, like Colonel Moore, who had already died, were posthumously attainted for high treason and their property confiscated (10) . It seems certain that this should have happened to Colonel Moore and his property, but the influence of his wife, Dorothy Fenwick, and her Royalist family saved him from losing the estates (3). Whether this means complete exoneration or by payment of a hefty fine is not clear.

Sir Edward More's 'distant kinsman Sir John Moore, a wealthy London merchant', came to his aid with a large mortgage in the 1670s (4). When Sir Edward died in 1678, the debt of £10,000 was inherited by his son and heir Sir Cleave More. By 1691 the debt had risen to £12,650 and, as we have seen, at the time of Sir John Moore's death in 1702, his will gave its value as £13,000. Sir Cleave More failed to pay off any of the debt; instead he had let it accumulate.

The engraving reproduced above, which belongs to the Moore family, is described as a 'Portrature and Coate Armour' of Sir William de la More, who was 'made Knight Banneret by Edward the Black Prince at the Battle of Poictiers in France' in 1356 (11). Knights Banneret were raised to that rank on the field of battle to mark conspicuous action or leadership and their rank was superior to that of knights bachelor (12). Sir William is shown holding his banneret, the armorial device from which the rank is named. It was created from his banner or pennon, a swallow-tailed flag with his arms painted on it. This was done ceremonially on the battlefield by cutting off the swallow tails, hence 'banneret'. Sir William is described in the caption as 'Ancestor to the present Sir Edward More of More hall and Banke hall in Lancashire Baronet'. Sir Edward More, described above, was made a baronet in 1675 and died in 1678, so the caption dates the engraving between those years, ie 1675 and 1678, some 320 years after the battle. The picture itself shows a man in 17th century armour and the fashionable style of the facial hair is also of that period (comparison with portraits of King Charles I by Van Dyck show remarkable similarities in these features). So the engraving is a 17th century interpretation and cannot possibly be an actual resemblance. A further puzzle is the fifth line, which is in smaller script and has been added after the full stop at the end of line four. It reads:

'of which family Sr. John More [sic] of London Knight & Alderman is lineally descended'.

A search on the web has revealed a very similar version of the 'portrature' in the possession of the National Portrait Gallery (NPG) in London. On close inspection, we can see that this is clearly a different engraving, but meant to represent the same figure. The Appleby Moores' version is a relatively immature and less elaborate sketch and the head has a more youthful appearance. The NPG version is identified as 'William de la More:(floruit [flourished] 1327-1358) Landowner and supposed chronicler' and attributed as 'possibly by Robert White, line engraving, 1679'. This agrees well with my deduction of 1675-78 for the Appleby Moores' version. The caption is similar to that of the latter, but lacks the fifth line (13). Taken with the evident differences, the additional fifth line of the Moores' version points to the probability of it being a copy of the original, with details of Sir John Moore's connection added. These record only that Sir John Moore was 'Knight & Alderman' and do not mention his ultimate honour of being Lord Mayor. So the extra line must be almost contemporary, having been added to the engraving before he became Lord Mayor in 1681.

But why was the original engraving made? The answer comes from a most unexpected source. The web search also produced a 'fictitious portrait' (one amongst others) of George Washington in the New York Public Library (NYPL) (14). The figure, posture and background are similar to that of Sir William de la More, except that the head has been replaced by that of George Washington, rather awkwardly facing over his right shoulder. Interesting though this bizarre portrait is, the importance to us is in the notes that go with it. The NYPL attributes the Washington print to a much later Englishman, John Norman, working in America c.1774-1814 and comments that it is 'a figure in armor that he copied, along with the background battle scene, directly from an engraving [of] William de la More in John Gwillim's 'A Display of Heraldry', a 1724 edition of which was in the possession of Norman's acquaintance John Coles, Sr.' Editions of Gwillim were published intermittently from 1610, the last ones being in 1678/9 and 1724 (15).

The 1724 edition would have repeated the More genealogical details, including the engraved illustration of Sir William de la More, which must have first appeared in the 1678/9 edition. So it must be concluded that the original engraving was prepared for the More entry in Gwillim's Heraldry. Without access to a copy of the work, we must use the information given under the surviving prints and the text information from Gwillim helpfully recorded by Nichols. These are the two texts:

The engravings are both inscribed:

'The Portrature and Coate Armour of Sr. William de la More

Ancestor to ye. present Sr. Edw: More of More:hall and Banke:hall

in Lancashire Baronet wch. sd. Sr. Will: was made Kt. Banneret

by Edw ye. Black Prince at ye. Battle of Poictiers in France.'

and the Appleby Moores' version has a fifth line added:

'of which family Sr. John More of London Knight & Alderman is lineally descended.'

Nichols also has this footnote to the entry for Norton juxta Twycross, where Sir John was born:

In Gwillim’s Heraldry p.194, sect.iii. c.16 sir John More [sic], knt. is described as “lineally descended from the family of More, or de la More, baronets, of More-hall and Bank-hall in Lancashire, an antient family whose ancestors have there continued for above 20 generations, as appears as well by divers antient deeds now in the custody of Sir Edward More baronet, as by the atchievements and inscriptions engraven on the walls of the said houses."'(16)

Significantly, Gwillim spells Sir John's name 'More', as it is on the engraving. From all the assembled evidence therefore, there can be no doubt then that Sir John Moore and Sir Edward More were descendants of the same family. They were the same generation and both were involved in the submission of the entry for Gwillim's Heraldry. The driving force may well have been Sir John, who was very much in the public eye and out to confirm his status despite his nonconformist background (see below). Sir Edward, as the receiver of generous financial assistance from Sir John, would have been a more than willing helper.

An Embarrassing Relationship

I have suggested that Charles Moore Sen. was the younger brother of Edward and Richard More, the sons of William More (1538-1602) by his second wife. The family can be reconstructed from the dating evidence available (17). The long-lived Sir John Moore (1620-1702) and Sir Edward More (1634-1678) were of the same generation (see CHART 2 above). If my suggested link between the families is correct, they were second cousins. Thus Sir John's father Charles Moore Jun. and Sir Edward's father Colonel John Moore, the regicide, were first cousins. The generation difference between Sir Edward's son Sir Cleave More and Sir John made him 'second cousin once removed', a more difficult concept perhaps, but in his will, Sir John Moore did not even call him a 'kinsman'. In the 1670s his generosity had extended to helping Sir Edward More who was struggling with the burden of his father's indebtedness. The fact was that Sir John had been helping, not just his own kith and kin, but the close family of a regicide. Later, in Sir John's conformist years, this became an unwelcome embarrassment for him and may have been the main reason for not giving any details of the current Lancashire mortgagee, Sir Cleave More, in his will.

Sir John Moore's Early Nonconformity

The issue of Colonel John Moore's involvement with the death of King Charles I would have been sensitive to Sir John Moore because of his own early religious and political leanings. The young (Sir) John Moore was a nonconformist and supporter of the Whig party in the City of London. The main religious doctrinal dispute in the early years of Charles I's reign was between the Arminians with their emphasis on the sacraments, led by Archbishop Laud and promoted by the King, and the Calvinists who believed in predestination. Sir John, in his youth, presumably aligned himself with the latter, having been instructed in Calvin's catechism at Ashby Grammar School (18). Little is known about his activity during the period of Civil War, but in 1642 as hostilities began, his father's cousin Colonel John Moore was colonel of the militia guarding Westminster and the City for the Parliamentarians. John would have been in his early 20s and recently have completed his apprenticeship in the Grocers' Company. The young man could hardly not have been influenced by his zealous relative but we do not know if he participated in anti-royalist action. After a spell in Liverpool, Colonel Moore was in Westminster up to the time of the King's execution in 1649, so there must have been continuing opportunities for contact between the two men. Colonel Moore died in 1650.

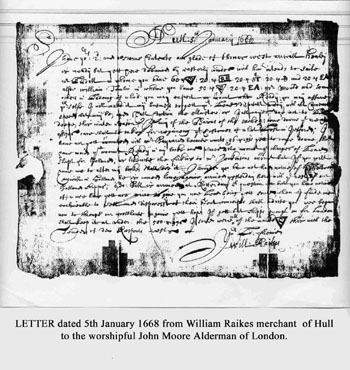

John Moore meanwhile was developing his trading activities and beginning to make money. By January 1668/9 he was exporting lead to Holland and wool to London from the port of Hull in Yorkshire - in addition to his trade in the City of London as a member of the Grocers' Company. His agent in Hull, another thriving merchant William Raikes, see letter below (19), was also a parliamentary sympathiser. In 1652 Raikes's appointment as mayor of Hull was supported by the republican Government in London and in 1661, after the Restoration, he agreed to be appointed alderman only to avoid paying a hefty fine. So rapidly did John Moore accumulate wealth from all his trading activities that, within about five years of this letter, he was able to provide Sir Edward More with a large mortgage on the Lancashire estates, valued at £10,000 in 1678.

WILLIAM RAIKES'S LETTER TO ALDERMAN JOHN MOORE JANUARY 1668/9

Click here for Transcription

(pdf file, opens in separate window)

In London, John Moore also continued to hold nonconformist views for several years after the Restoration. With wealth and advancement in the Grocers' Company his turn came to hold various public offices in the City. Elected as alderman in 1666, he conscientiously refused the sacramental test, of taking the sacrament of the established church, and was discharged from office on payment of a £520 fine (20).

However, before long, in a surprising change of mind, he abandoned his former principles, apparently succumbing to the lure of high office and the pressure to conform. In 1671, he was elected alderman for Walbrook ward, this time submitting to the sacramental test (21). According to custom, he was knighted the following year. Because of his changed allegiance, there was considerable controversy in the City concerning his nomination as Lord Mayor of London when his turn came in 1681. Gilbert Burnet, Bishop of Salisbury reported: 'He had been a nonconformist himself, till he grew so rich that he had a mind to go through the dignities of the city: but though he conformed to the church, yet he was still looked on as one that in his heart favoured the sectories [dissenters]' (22). Nevertheless, by the dubious methods employed in elections at that time and with the King's backing, he was elected Lord Mayor, now as a loyal Tory. Narcissus Luttrell, a contemporary observer, noted in September 1681, at the beginning of his mayoralty, Sir John Moore was 'at present in the lieutenancy of the city militia', ie maintaining the restored King's peace (23). Contrast this with Colonel John Moore's role as Colonel of the London militia supporting the Parliamentary cause some 40 years earlier. Perceived by many as a 'turncoat', Sir John Moore was stalked by controversy throughout his year of office and beyond.

Turncoat or Loyalist?

But was this reputation of being a turncoat fair? Personal motives for attaining the most prestigious position in the City of London must have played their part, but there was also the wider issue of the stability of the country. The experiment of a republic had failed and Charles II, recalled to the throne, did not hold the absolutist views of his father. Invited back by Parliament, of necessity he had to listen to their wishes. The country had changed since Sir John was young man and as he grew older he may have reasoned that the best way forward for the country as a whole was under the restored monarchy sanctioned by Parliament. The City of London was the centre of activity of the Whig opponents of the court and as mayor Sir John chose to promote the King's cause in the City. The King later (1683) showed his appreciation for Sir John's 'unshaken loyalty' and 'constant fidelity' by granting Sir John an augmentation to his arms 'a canton gules [red square] charged with a lion of England'. The lion remains on the Moore Arms to this day.

Heraldic and Genealogical Trimmings

Rising in prominence in the City of the late 1670s Sir John was thus seeking to establish credentials which would boost his claim to be a sound supporter of the restored regime of King Charles II. His entry in Gwillim's 'Display of Heraldry' may be seen in that light. Presenting himself as honourably descended from the ancient Lancashire More family, with their arms which he would now display, he was establishing and claiming his status. Whether the king knew anything of the regicide relation, Colonel John Moore, let alone Sir John's financial support to the colonel's impoverished family, is doubtful. It was an awkward fact best not publicised. This would perhaps explain why the precise details of the connection of Sir John Moore to the Lancashire Mores were never disclosed.

Sir Cleave More and the Final Settlement of Debts

Opinions on the character of the young Cleave More were not very flattering: he was later described by his former tutor as a 'useless spark'. Nevertheless, with the premature death of his elder brothers in 1672, he became heir to the estate and at the age of 15 years in 1678, on the death of his father, he inherited the estates, the baronetcy and, moreover, the accumulated mortgage debts, which by this date stood at £10,000 [£1.34 million today]. By 1691 they had risen to £12,650. Sir Cleave's solution to the debt crisis was to marry into money. He married an Hertfordshire heiress, but desperate for her 'portion', he managed to do so without first obtaining the consent of her father, John Edmunds. Later, despite being separated from his wife, he shamelessly obtained a commission of lunacy against his father-in-law, with false testimony from bribed servants, and gained possession of her family's Hertfordshire estates with their income, said to be over £1,400 per annum. After protests from John Edmunds' fellow country gentlemen, the commission of lunacy was quashed and, with the release of his father-in-law, Sir Cleave More lost his ill-gotten gain as well as his reputation.

When John Moore of Kentwell inherited the Lancashire mortgage on the death of Sir John Moore in 1702, he promptly entered into a legal challenge in order to recoup the capital, but Sir Cleave More managed to avoid any action on foreclosure until 1712. Retiring from Bank Hall to the south of England to live on the estate acquired through his marriage, Sir Cleave eventually agreed with John Moore to repay the mortgage, now £15,000, on or before 29 September 1714. But in May of that year Sir Cleave complained that he needed more time to raise the money demanded by 'that unreasonable agreement' which he had only made 'because necessity forced me' (4). This further delay was no doubt encouraged by the fact that in January 1713/4 John Moore of Kentwell Hall had died at his home in Suffolk.

A Slow Sale

By the will of John Moore of Kentwell Hall (1714), the Lancashire mortgage was passed to George Moore (1688-1751). He was the eldest son of Thomas Moore, Sir John's eldest nephew and lord of Appleby Parva manor. So the problem of realising the value of the Lancashire estates had now passed to George who continued to put pressure on Sir Cleave More. Preparations were put in hand to sell the estates in 1717 but a sale was not achieved until January 1724/5 when James Stanley, 10th Earl of Derby, who already owned much of Lancashire, purchased the extensive Bank Hall domain including the manors of Kirkdale, Bootle and Linacre and all Sir Cleave More's other estates in Kirkby, West Derby, Fazakerley, Litherland, Little Crosby, Ellel, Horsam, Walton, and Liverpool (2). The sheer size of the whole domain explains the difficulty in finding a purchaser. Only a landowner of Lord Derby's standing would be able to afford it and, in what was necessarily a buyer's market, he would have pressed home his advantage to get a bargain. For Sir Cleave to receive anything from the sale would depend on whether it was he or George Moore who sold the property. This was because, with a loan unpaid, ownership was considered to reside with the mortgager, who had the right to sell the property (24). It would appear that the Moores had been reluctant to force the issue, preferring to use persuasion with the recalcitrant Sir Cleave. In any event, Sir Cleave finally lost all claim to his ancestral Lancashire estates with their sale in 1725. He died in London in 1730.

The Moores of Appleby finally inherit

George Moore (1688-1751) of Appleby Parva received Sir John Moore's accumulated mortgage capital in 1725. The Lancashire mortgage which had been granted to Sir Edward More in the 1670s, some 50 years earlier, was at last redeemed. Under the terms of the will of John Moore of Kentwell, George Moore was required to pay £6,500 of the £15,000 to relatives at Appleby Parva, a belated acknowledgement of the unrealised bequests of Sir John Moore's will, and to repay £500 with interest to Mrs Matilda Moore 'sister' (sister-in-law?) of Sir Cleave More. This would leave nearly £8,000 for himself (or perhaps more if he, rather than Sir Cleave, conducted the sale). Some of Sir John's 'fortune' had finally reached his family at Appleby. Coincidentally Thomas Moore, George's father, died in 1725 and he inherited the Appleby Parva estate to become lord of the manor. In ways that could not have been planned or foreseen, other portions of Sir John Moore's fortune came to Appleby Parva. Several of the well-off Moores were childless and willed the residues of their estates (after payment of smaller legacies) in such a way that wealth was funnelled down the Appleby line of the family.

Sir John Moore's Benevolence

During his lifetime Sir John helped his many nephews and nieces with loans, subsequently cancelled by his will, and made further bequests to them following his death. The benefits passed to an even larger number of the extended family in subsequent generations, principally through the will of his heir John Moore of Kentwell Hall. Two generations on, another key figure was Charles Moore, barrister at the Middle Temple in London, son and heir of John and Sarah Moore of Southgate. Between them, John and Sarah had inherited Sir John Moore's commercial properties in London from John of Kentwell together with Sir John's house in Mincing Lane and half of the estate of another uncle, the unmarried George Moore of Lambeth. In 1751 Charles inherited the estate of his uncle George Moore of Appleby Parva, who had remained unmarried. This included not only the Lancashire money and Appleby Parva manor itself but also the other half of the Lambeth bequest. So, when Charles obtained his father's estate on his death in 1756, significant amounts of Sir John's fortune came together to the benefit of subsequent generations. With well chosen marriages, the fortunes of the later Moores of Appleby Parva prospered and the estate reached its zenith during the first half of the nineteenth century. This lead to the accumulation of land and the development of three grand houses: Snarestone Lodge, the White House at Appleby Magna and Appleby Hall, an enlargement of the ancestral home at Appleby Parva.

That the Appleby relations received nothing in the short term was due to the large amount of money tied up in the mortgage which Sir John had granted to his second cousin Sir Edward More of Bank Hall in Lancashire, itself a huge act of generosity. As executor to Sir John Moore's will, John Moore of Kentwell was unable to pay all the legacies until the Lancashire mortgage was redeemed and it was the Appleby Moores, his cousin Thomas, squire of Appleby and his brother, farmer George, that he made wait. Relations with these two had been strained during the construction of Appleby School: their inept supervision of the building work had caused many problems to John of Kentwell, then Sir John's agent in London. John's seemingly perverse administration of Sir John's will, to the Appleby Moores' short-term disadvantage, was perhaps influenced by that experience. Later generations however did benefit enormously and it can now be seen that the build up of wealth which produced the Appleby Hall estate had its origins in Sir John Moore's undoubted benevolence.

Notes and References

For details of Wills see Part 1(In Focus 31)

1.Nichols, Vol IV, 2, Appleby Parva, 440

2. British History Online, VCH Lancashire 3, 1907, 35-40 Townships, Kirkdale. At the time of publication it was decided, unhelpfully, to modernise the spelling of the Lancashire family name to 'Moore'. To distinguish the families, I have reverted to the original 'More'.

www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=41286

3. British History Online, VCH Lancashire 4, 1911 Liverpool Castle, 4-36

www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=41370

4. D Hayton, E Cruickshanks, S Handley, 2002, CUP, The House of Commons 1690-1715, 925-26, Sir Cleave More

http://books.google.com/books/cambridge?id=LGv4-_VAeJAC&pg=PA926&dq=cleave+more#PPA925,M1

5. The accounts in VCH3 (1907) and VCH4 (1911) (Notes 2. and 3.) differ in the 1246 name Randle or Ranulf. This may be due to different readings of the original script. Both are early variations of the name Randolf.

6. Nichols, Vol IV, 2, Appleby Parva, 439: 'And in the 41st year of the reign of queen Elizabeth [1599], sir Edward Griffin, knight [of Braybrooke, Northants], conveyed the said manor and premises to Charles Moore, who was lineally descended from the Moores of More and Bank Hall, Lancashire', with the note 'see Gwillim's Heraldry, p.430'.

7. I have already argued (in In Focus 12) the case for two Charles Moores, the senior one being the purchaser of Appleby Parva in 1599, the junior one being a 'husbandman', ie tenant farmer, at Norton and the father of Sir John Moore and his siblings, Sir John being the second child born in 1620. I am aware that the two pedigree charts (Moore and Nichols) show the father of Sir John and his siblings as the lord of the manor in 1599. He must have been born by 1581 at the latest, ie 18 years of age, in order to own the property. It seems unlikely, although not impossible, that a man on acquiring property would wait nearly 20 years before marrying and starting a family of seven children.

8. Colonel John 'Moore' used the spelling common in the south of England but his grandson Sir Cleave 'More' continued to use the Lancashire spelling when he went to Westminster as an MP. Hayton, Cruickshank and Handley (Note 4.) maintain the two spellings for the biographical note on Sir Cleave More, referring to 'disputes between More and Moore'. The reference to 'Sir Cleave Moore' in Sir John Moore's will may simply be the work of the London clerk who copied the document into the wills ledger.

9. Colonel John Moore, Regicide:

www.british-civil-wars.co.uk/biog/moore.htm

10. Punishment of regicides:

www.british-civil-wars.co.uk/biog/regicides.htm

11. The full caption of the engraving is as follows:

'The Portrature and Coate Armour of Sr. William de la More

Ancestor to ye. present Sr. Edw: More of More:hall and Banke:hall

in Lancashire Baronet wch. sd. Sr. Will: was made Kt. Banneret

by Edw ye. Black Prince at ye. Battle of Poictiers in France.

of which family Sr. John More of London Knight & Alderman is lineally descended.'

Sir William de la More is depicted holding a lance on top of which is his truncated banner (banneret) with his coat of arms (the greyhounds etc as in the Appleby coat of arms). The Battle of Poictiers (Poitiers) took place in 1356.

A copy of the engraving provided by Mr Peter Moore for reproduction here is kindly acknowledged.

12. The Imperial Society of Knights Bachelor: Knights Banneret: 'a swallow-tailed flag called a pennon, with his arms painted on it'. See:

www.iskb.co.uk/history.htm

13. National Portrait Gallery copy has only four lines of inscription. The NPG gives dates for the engraving and Sir William de la More. The minor discrepancy between the dates 1678 and 1679 may be due to the use of different calendars, dates between January 1 and March 25 being 1678 by the old style calendar or 1679 by the modern one. The dating '1678/79' for one of Gwillim's publications (see below) may well have the same explanation.

www.npg.org.uk/live/search/portrait.asp?search=ss&sText=william+de+la+more&LinkID=mp87097&rNo=0&role=sit

14. Fictitious Washington portraits, NYPL, see (fourth example):

www.nypl.org/research/chss/spe/art/print/exhibits/revolution/selection4.html

15. The crucial evidence from John Gwillim's 'A Display of Heraldrie' is quoted by Nichols under Norton (see 16.). Editions of Gwillim were published in 1610, 1611, 1632, 1638, 1660, 1664, 1666, 1678/9 and 1724. John Gwillim himself died in 1621, see:

www.btinternet.com/~paul.j.grant/guillim/sourcenotes.htm#eds

16. Nichols, op cit, (Norton) p 851* ‘The Moores of Appleby, and the Abneys of Willesley, Derbyshire, have considerable estates here. Sir John Moore2, lord mayor of London in 1681, was son of a husbandman at Norton. Footnote 2: ....In Gwillim’s Heraldry p.194, sect.iii. c.16 sir John More [sic], knt. is described as “lineally descended from the family of More, baronets, of More-hall and Bank-hall in Lancashire, an antient family whose ancestors have there continued for above 20 generations, as appears as well by divers antient deeds now in the custody of Sir Edward More baronet, as by the atchievements and inscriptions engraven on the walls of the said houses.” MS in the Ashmolean Museum, No. 834.’

17. Reconstructed family of William More (1538-1602) Dates in bold are definite; others tentative.

son with first wife: 1566 John;

sons with second wife: 1570s Edward (Edward's son John b.1599); next son Richard;

suggested youngest son: late 1570s Charles - purchased Appleby Parva 1599

suggested second generation: Charles's son Charles c.1600,

suggested third generation: Charles ?1619 and (Sir) John 1620

18. 'Tory' and 'Whig' are used here to describe the 'Court' and 'Country' political factions respectively.

The evidence for Sir John's attendance at Ashby Grammar School is given by Alan Roberts in Turbulent Times - 17th Century Appleby on this web-site: viz. a letter from Samuel Shaw of Ashby to Sir John, dated 14 March 1693, referring to Ashby as ‘the place of your former education’: ‘Captain Stewart MSS’, HMC Series 13, Tenth Report, Appendix iv, 138.

The Calvinistic regime at Ashby Grammar School is described in A Country Grammar School by Levi Fox, 1967.

19. Letter from William Raikes to Alderman John Moore 1668, photocopy courtesy of E and R Shanahan, postal historians, Flinders Creek, Queensland, Australia, 2001

20. R Dunmore, This Noble Foundation, 1992, 4-5

21. Dictionary of National Biography, Sir John Moore

22. Gilbert Burnet [Bishop of Salisbury] History of My Own Time ed. O Airy 1900 I pt 2, 335

23. Narcissus Luttrell, A Brief Historical Relation of State Affairs I 1678-1689 OUP 1857,

'1681 Sept 29th Sir John Moore ... at present in the lieutenancy of the city militia'

24. Mortgage: "What most people call a mortgage is really two different things. There is an underlying loan agreement under which someone advances money to the homeowner for a period of time. This will be subject to various terms and conditions that deal with the repayment of the loan and interest. What makes the arrangement a mortgage is that the lender has special rights or charges over the property to ensure that the loan will be repaid. The "mortgage" is the charge rather than the loan agreement itself. ... Originally most mortgages in England and Wales made the lender the actual owner of the property until the loan was repaid, but this kind of "mortgage by demise" has not been allowed since 2002." - Mark Loveday, barrister, writing in The Times newspaper 'Bricks and Mortar' section 6 March 2009.

©Richard Dunmore, March 2009

Previous article < Appleby's History In Focus > Next article