Appleby History > Memories > Growing up in the 1940's Part 1

Growing Up in the 1940s

Part 1: My Early Life

by Anne Silins

Anne Silins, nee Bates, lived in Appleby Magna until her family emigrated to Canada in 1951. Now living in Ontario, Anne has recorded her memories of her childhood at the family shop in Church Street, and at Lower Rectory Farm in Snarestone Lane

I was born in the upstairs front bedroom, the room above the Shop in Church Street, Appleby Magna in October 1937. Some of my earliest memories are of that Shop and of the life which surrounded the Shop. I still cannot believe how lucky I was to have been born in that village of Appleby. It has been a blessing. I learned so much in those years that I lived and grew there. Lessons from the villagers that I came in contact with daily, and lessons which have helped me all through my life.

The village shop back then was so much more than a place to buy merchandise. It was a social place, a place where women gathered to buy their bits and pieces each day. The stock was arranged on shelves all around the walls. The shop was filled with the most wonderful aroma. The smells of cooked meats and spice, fresh bread and cheese all mixed with soaps and sweets. The whole place was full of noise: customers talking, the patting and slapping of butter, the clang of weights on the scale, the sound of knives being sharpened and the ring of the door bell.

A large round of Leicester cheese sat on the counter. Hanging near it was a wire with wooden handles at each end, which was used to cut the cheese into smaller pieces. Customers would indicate the required size by holding up a thumb and forefinger.

I remember ‘Sunlight’, ‘Lifebuoy’ and ‘Magical’ soap packets were on the low shelves just where a little girl could play with them. Unwrapped, long bars of scrubbing soap sat next to them and hanging from a nail close by, a very sharp knife which was used to cut off the amount a customer needed.

It was wartime and everyone had a ration book. Ration books were for foodstuffs, clothes and petrol. The women of the village were very careful when making their purchases, and they guarded their ration books with great care. People in the village never starved, but the threat of famine did become real when merchant ships were sunk by U-Boats in the Atlantic and imported food stuff was lost.

The Bates grocery and bakery shop, 1913 - click image for larger view

Our house which was joined to the Shop was a rambling brick house with the garden going all the way down to the village brook. Other buildings were nearby, the butcher’s shop, the bakery, a garage, stable, pig sty and sheds. There was no organized plan of the sort we expect today, because sheds and additions had been made over the years as needed. A walk down towards the brook took me through the Dig for Victory garden. Everyone in the village had some sort of Victory garden for their own vegetables. It was a matter of pride for everyone to grow some of their own food, a patriotic duty and a need. My research tells me that during the war agriculture in the British Isles was expanded to the maximum, the number of allotments for growing vegetables doubled to nearly 1,500,000 and there were some 7,000 pig clubs started. People kept a pig and fattened it on kitchen waste.

Right down by the brook was a wonderful wild area filled with weeds and blackberry vines. As I grew bigger I loved to wade in the brook until the water was right to the top of my black Wellington boots. The water was clear even though a number of cottages ran their waste water straight into the stream. I would watch stickleback dart about trying to hide behind pieces of waving weeds. I tried to catch them in a jar, and if I was lucky I would take them back to the kitchen so that I could watch them grow. The jam jar always went missing after a few days. That village brook was a wonder, it was like the back street of the village. We children waded in it for the entire length of its passage through the village. Passing the backs of the cottages with their kitchen windows looking down on us, we would watch a kitchen sink drain into the brook and see a few lingering bubbles form in the water. In the clear water we could see pebbles and soft sand through the water, as we waded we stirred this clouding the water and leaving momentary evidence of our passage.

At the bottom of Mawbys Lane there is a row of cottages. These cottages and the road are actually built right over the brook. A brick tunnel runs under the cottages and Mawbys Lane. The brook flows through and makes a right hand turn in the middle. We used to make paper boats and set them on the water, then race over the stile and across the road to see whose boat emerged first. It was d'aring to creep through this tunnel'. You were especially brave if you did this alone. On one solo trip through the tunnel I was the unlucky child whose timing was really off. The contents of a sink from the middle cottage just happened to be emptied from above as I, bent over walked through the tunnel. There was much ‘wagging of the finger’ in front of my nose when I arrived home with my clothes wet and smelly and my black ‘wellies’ filled with water because I had also misjudged the water level as I ran out of the tunnel.

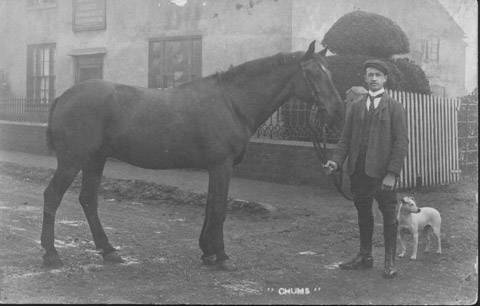

Charles Thomas Bates outside the shop, 1899. Click image for larger view

The open door of the hay loft above the stable made an excellent ‘look out’ onto the main yard and gave me an excellent view of Church Street. I would sit and watch the activities of the neighbourhood for hours from my perch and at tea time I would relate the activities of all the people who had passed by. For the most part I received disapproving frowns for my efforts, but sometimes amused interest. This hay loft smelt of leather, wood, manure, and of course hay, such lovely smells. Now if I pass a field of ripe hay on a summer afternoon I can close my eyes and be right back in that loft in Appleby Magna, as good memories come flooding back to me.

Word spread on the day a pig was being killed at the butcher’s shop and the young boys in Church Street would do any chores just for the promise of a good pigs bladder. These pig’s bladders made excellent, inexpensive footballs and were kicked up and down the street with gusto.

Life around the Church and Churchyard.

The Appleby churchyard and cemetery were places of great fascination for us children. The churchyard is located immediately around the sides of the church. When I grew up there were many headstones in the churchyard, both slate and carved stone, all standing upright to mark a grave. I found it sad to see on a visit back to Appleby that now the head stones and slates lie flat. Some even are placed to form walkways and others are broken. All this I understand is to aid in grass cutting, necessary when we all live such busy lives.

The cemetery was across the road from the church, adjoining Mr. Parker's meadow and the school playground It was a good size and I remember it as only half filled. The hedges that surrounded it had lots of blackberry bushes. It was a good place in late summer to have a feast if the birds had not beaten us to them. Here in the cemetery the headstones still remain upright. To have taken these and laid them flat to aid mowing equipment would have caused an outcry, as relatives of those interned there were still very much alive.

We children played a game similar to tag in the cemetery. The home base, where you were ‘safe’, was the headstone of any person who had been a member of your family. I stood a good chance of winning, even though I was the youngest and couldn't run as fast as the others. I had a lot of ancestors in the cemetery and I quickly learned the location of all their graves. Disputes arose from time to time over the name of an aunt, cousins or other distant family members. Some playmates were not above inventing a few relations in order to be ‘safe’ and so not ‘out’ of the game. For justice to be done we would all march off to the mother of that playmate. The mother would counsel us and verify names. Many mothers were amazed at our interest in family history, until they realized that our games involved family headstones. We were never forbidden to play in the cemetery, they only asked that we never step on a grave as this was disrespectful. We ran in the space between the graves, the paths making a grid or checkerboard pattern. The words we use to-day for death and dying would have been foreign to the children of Appleby. Euphemisms never got in the way of our understanding. Adults never attempted to disguise reality with fantasy, and so we were didn’t hear the words that are used today such as; passed on, passed over, passed away, gone away, expired, lost, taken, departed or even ‘snuffed it’. Today this would be considered morbid, but it was a part of our daily lives.

At the centre of the village was the church. Appleby church was also the social centre of the village, at least for the women and children. The Pubs, of which there were four, ( Queen Adelaide Inn, the Crown Inn, the Black Horse Inn and the Moore’s Arms) were the social centre for most of the men. For us children playing around the church kept us out of harm’s way so we were not in the path of a horse and cart, or the occasional car or delivery van.

We children were usually on hand when a new grave was being made ready. The grave digger would arrive pulling a small wagon containing his spades, axe and picks. He would take off his coat and hang it on a nearby branch. He began by cutting and rolling back the turf. Next, he began to dig, sometimes hitting a root of a tree. We would watch each swing of the axe as it caught the sunlight. We paid close attention if the sharp axe hit a rock. It was rumoured that this could have been an ancient burial ground and we listened anxiously for the sound of the metal spade meeting bone or coffin nail. We stood on the periphery with the grave digger between us and whatever might be down in the hole. Husbands and wives were buried in the same plot, and we were never sure how the digger knew when to halt so that he did not disturb the first occupant. Word would circulate among the children if a second placement was being prepared and we then moved back behind the hedge, afraid of seeing the lid of the already buried coffin.

When someone died, they were laid out in the parlour of their own home. Women dressed in black while the men wore black arm bands. There was usually an interval of three days from the time of death to the time of burial. This was sufficient for the village carpenter to build a coffin. The bier was brought out and on the day of the service it was taken to the home of the deceased. The coffin was placed upon the bier and relatives and friends accompanied the body, the men pulling the bier while the women followed on foot. Along the route all curtains would be drawn and if the procession passed us we knew that we should cover our eyes or bow our heads.

I can only remember the names of two women who kept the church clean and the church linens fresh. They were Mrs. Dora Gothard and Mrs. Gladys Gothard, and they also would cut fresh flowers to decorate the altar and the pulpit for the Sunday services. This was a labour of love. Love for the church, and love and service to the Church.

After the funeral service in Church the coffin would be carried across Church Street to the cemetery and lowered on ropes into the prepared earth. The grave was filled in right away by men who had been standing nearby, leaning on their shovels. Sometimes a glass of beer followed their work. Then the cemetery belonged to us children again.

The Church, Cemetery and the Church School (now the Church Hall)

My School Days

My school days began in the one room Chapel Infants School which was just a short distance along Church Street. It was called the Infant’s Chapel School not because they hoped we would all turn religious, but because the building had been at one time a Wesleyan Chapel. There was one large room with a balcony across the back one third of this room. If you had misbehaved you were sometimes sent up the narrow staircase to the balcony and told to stay there until you remembered how to behave. In my case I was sent up there far too often for talking - chatting in class. I didn’t mind too much, I would sit in one of the front seats and peer over the wooden rail to watch and listen to the teacher. The teacher stood at what must have once been the pulpit. We sat and stared up at her, or often in my case from the balcony, peered down at her. Our teacher would try without too much success to keep us young pupils in order, but it was difficult to keep us quiet in class.

When the Hunt came through the village or when someone was needed to run errands or do small tasks at home, children were kept out of school. Children of my age were given ‘a good ‘idin’ for not ‘stopping’ at home to help when needed. ‘A good ‘idin’ varied according to the temperament of the giver. It could be a good thrashing or a few clouts about the head. Needless to say children tried to avoid this and if it couldn’t be avoided, then they would brag about it at school.

After two years I advanced to the Church School. This school was opposite the Church in Church Street. It was a fine old building, but had to hold far too many children. The Appleby Grammar School was not in use as a school in the 1940's, it sat empty. At the Church School there were cloakrooms at each of the two front entrances and outhouse lavatories in the back playground.

Many levels of learning were attempted in the school. Sections were curtained off to designate different levels. Teachers and pupils alike strained their ears to catch what was being said. The noise level was high as some students recited their times tables, while others recited poetry. The smaller room contained the students in the top or last year. Their numbers were small, many left to find work as soon as the pits or the farms would take them on. The head master's office was in this area and he taught the older children.

There was a big iron stove in each room. It was set up against the wall. An iron railing, or ‘guard’, as we called it, closed in the three open sides. This was to protected us from falling against the stove, and it also served as a place to hang wet coats, hats and scarfs on rainy days. Our Wellington boots we cleaned off at the boot scraper just outside the door. We placed our boots around the guard rail, the open ends towards the heat, they fanned out like the spokes of an enormous wheel. It came as a complete surprise to me that Wellington boots were not always waterproof footwear. Many children came to school with boots having holes and even great rips in the soles. Taking our boots off in the school cloakroom produced a wonderful spill of water, making the floor one enormous, slippery puddle. Of course, none of this clothing really dried by noon hour or by the end of the school day. Mitts were pulled onto hands that throughout the winter became raw and rough. Children had no guarantee that coats or jackets would even dry overnight at home, though at home clothes lines were strung up across the kitchen where, with luck their things might be almost dry the following morning. The only way some of us escaped from the usually slightly-damp-from-the-last-outing clothing was to be quarantined for a childhood disease. Mumps, measles, chicken pox, scarlet fever or just the common cold could keep children indoors for two or three weeks each winter. I really loathed winter clothes. I had to wear white cotton bloomers and the regulation navy bloomer, at the same time. My family’s rules said I couldn't wear anything but white next to my skin. Both pairs of bloomers were held up by stout elastic threaded through the waistband. Next came a white cotton vest, a slip, white cotton blouse, and finally the navy-blue pleated jumper or tunic. To-day, my grandchildren fling on their lightweight, weather-resistant, brightly coloured winter wear over casual, easy-care indoor clothes. They zip or Velcro up, pull on cosy practical boots, insulated gloves and fashionable hats, and dash out of the door. If they do come home wet, they are spared the clinging odour of wet wool -- everything goes into the clothes dryer, and is quickly ready for the next trip outdoors. "Children don't know how good they've got it to-day," we say. Back in the ‘dark ages’ women repaired the worn-through heels of school socks with a well-placed tiny stitch. Those socks were never quite comfortable, however you could always feel the seam of that damned ‘darned’ spot. Even our bloomers - ‘knickers’ were darned. I would watch children wiggle in their seats as they adjusted around the thick seams. It was war time and the clothing coupons had to stretch just as far as the money did. Yes clothing is better and easier to care for today!

My time at the Appleby school came to an abrupt end. My family had watched my school progress attentively and it was decided that I should be moved to a school in Ashby. It was in September 1944 that I started attending the Ashby-de-la-Zouch Modern School for Girls in North Street. At first I caught the bus for Ashby on the Church corner at the Alms Houses. For company I had the students who attended the Grammar School and the people who worked in the factories in Ashby. There I was, at school in Ashby away from my village school friends; a nervous, fidgety, couldn’t sit still little girl. I bit my nails and always had a frown on my face. After a few months I fit in and settled down to the new school.

By Anne Silins (nee Bates)

Part 2 - Life at Lower Rectory Farm