Appleby History > In Focus > 18 - Wealth and Poverty

Chapter 18

Wealth and Poverty

The Growth of Wealth and Poverty in Appleby in the Late 18th and Early 19th Centuries

The Evidence of Appleby Parish Registers

by Richard Dunmore

Inclosure came and trampled on the grave

Of labour's rights and left the poor a slave

John Clare (1)

When Charles Moore, lord of the manor of Appleby Parva from 1751 to 1775, secured the enclosure of the commons and remaining open fields of Appleby in 1772, the old social order which had survived from early medieval, or even Saxon, times was changed for ever.

The Old Social Order

The world that was lost consisted of a well established social structure ranging from wealthy land-owning employers to humble day-labourers who obtained work on a daily basis. At the top of the social pile locally were the yeomen farmers who owned their land and employed men from the village as agricultural labourers when required. Next were the husbandmen, lesser farmers who had a smaller acreage and leased from a landlord, but they worked the land on their own account and also employed one or two farm workers.

A broad range of tradesmen and craftsmen formed the next layer of society. They had small plots of land, crofts and orchards perhaps, in addition to their trade or shop. With little security at all, the agricultural day labourers were near the bottom of society. They were better off only than those with no income, the paupers. The poor were often widows and orphans, who had lost their family bread-winner, or the elderly or those who were disabled and unable to work. These ‘undeserved poor’ were supported through parish rates.

This social structure of rural society was delicately balanced with members dependent on each other and on their rights within the community. This structure was not in any way egalitarian, but, having evolved over the centuries, was generally accepted. Poorer members of society, living in humble cottages, were able to survive with sporadic employment because of their rights to pasture animals on the commons.

Under the open-field system of farming, each farmer worked strips of land which were scattered about the fields and allocated by communal agreement. The inconvenience of this to the larger land holders had already led them to consolidate, and enclose, parts of their holdings by exchanging parcels of land. But smallholders still retained their own strips and all had rights of grazing on the large areas of common.

Enclosure

With the enclosure of the whole parish, including the heaths and commons, these rights were swept away. The earlier ‘ancient’ enclosures were confirmed and the remaining land divided up afresh and awarded to individual landholders. The larger farmers wanted to divide up the common land and incorporate it into their farms. This would enable them to work more land with increased efficiency; and so improve their output and profits.

Common rights were of greatest value to the poorer sections of society and their loss was a devastating blow. A small allotment of land may have been sufficiently large to keep hens and grow vegetables, but it became impossible to support a few cows which could hitherto be kept on the commons. The larger landowners regarded those who lived off the commons as idlers and petty thieves. No doubt there were some of these, but the farmers failed to realise, or chose to ignore, the plight of the honest poorer smallholders. The economics of their husbandry was so finely balanced that the loss of the commons and heaths made their living impossible.

Changes to the Countryside

Enclosure also brought about huge aesthetic and ecological changes to the countryside. This was felt by all those whose lives were centred on the land. None has expressed the sense of loss, anger and despair more eloquently than the ‘peasant poet’ John Clare (2). Naturalist and poet, he was born at Helpston in Northamptonshire and lived through the enclosures of his native parish. He felt most keenly the loss of heathland and commons, trees, bushes and spinneys, bubbling springs and meandering brooks - the particular habitats of the fauna and flora he had known and observed all his life.

Above all of this there was the loss of freedom to wander the lanes and baulks - pasture ridges or headlands which gave access to the open fields - as the countryside was staked out with post and rail and these access strips went under the plough along with the heaths and commons themselves. Not only were the lowest agricultural workers pauperised, they were excluded from the very land whose access they had so recently enjoyed.

The Evidence at Appleby

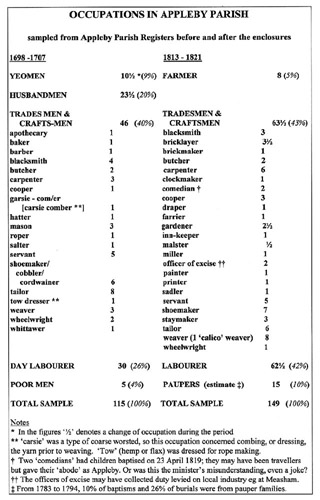

Evidence of the changes which took place in rural society is to be found in Appleby Parish Registers (3). In the earliest register entries little information is given other than basic names and dates, but for a period before the enclosures, and again afterwards, the occupation is given of the family breadwinner (father, husband, &c) for each register entry. Examination of the changes in these occupations after the enclosures shows how much village society was consequently altered.

Professions, trades, crafts and other occupations are first given against each register entry from 1698 to 1707 to justify levels of taxation imposed on register entries as a means of paying for the war against France (4). Later, between 1783 and 1794 poor people are named as being exempt from a similar tax (5). Finally, from the year 1813, standard baptism forms were introduced by Act of Parliament (1812) which required the occupation of the child’s father to be stated (6).

Society after the Enclosures

After the upheaval of land tenure resulting from the Enclosure Award of 1772 (7), yeomen and husbandmen disappeared and were replaced by a much smaller number of farmers. The numbers of tradesmen and craftsmen whose living was not directly dependent upon the land barely changed. However the largest change was in the number of labourers which was greatly increased. On the evidence of the 1783-94 registers the numbers reduced to poverty were considerable. My calculations of the numbers of each of these social groups before and after the enclosures are given in the table which follows.

Wealth and Poverty

Although the list of occupations is of interest in itself, the proportionate changes in each main category are of great significance in showing the wealth of the land being concentrated into a few hands. Around the year 1700, the yeomen and husbandmen - 34 men farming on their own account - amounted to 29% of the working population. After the enclosures, around 1820, only 8 men, or 5% of the employed, could be described as farmers and, with the commons ploughed up, this favoured few were working a much larger acreage.

A small number of former husbandmen may have retained their independence by switching to employment as crafts- or tradesmen. These increased marginally from 40% to 43%.

However, a much larger number of men were reduced to the status of labourer and many others to poverty. Labourers increased from 26% to 42% of the workforce, dependent on employment by the wealthy landowners.

Around the year 1700, 4% of the workforce was unemployed. With a population of around 600, that means 24 people below the bread-line. After the enclosures, in the period 1783 to 1794, 10% of baptisms and 26% of burials were from pauper families. I have assumed 10% poverty for the post 1812 data but the situation may have been worse (8). At the beginning of the 19th century therefore when the village population had risen to around 1100, at least 110 people (10%) were living in poverty, probably more.

Appleby Workhouse

Legislation of 1723 allowed for the relief of the poor by permitting the construction of workhouses by individual, or groups of, parishes. Those applying for parish relief were obliged to enter the workhouse and, in return for being housed, clothed and fed, had to perform allocated work. This was to deter casual applications, a principle which was continued when Union Workhouses were created later. John Clare bitterly described workhouses as ‘prisons’ constructed in the wake of the enclosures:

Thus came enclosure - ruin was her guide

But freedoms clapping hands enjoyed the sight

Tho comforts cottage soon was thrust aside

And workhouse prisons raised upon the scite (9)

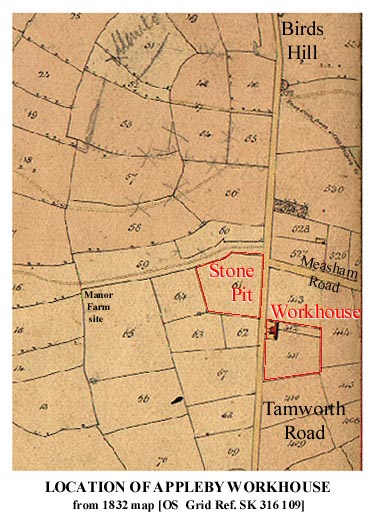

The Appleby parish map of 1832 shows the Appleby Workhouse situated well out of the village on the turnpike road from Measham to Tamworth, a short distance south-west of the junction with Measham Road (10).

But, when was the workhouse built? The clues to answering this question lie in its location. Firstly, it is on the turnpike road almost opposite the Stone Pit owned by the ‘Surveyors of the Roads’. Secondly the site of the Workhouse building together with its yards, gardens and adjacent ‘close’, ie enclosure, fits neatly into the pattern of enclosed fields. The location adjacent to the stone pit cannot have been accidental. The old ‘High Road’ was turnpiked in 1760 and the surveyors responsible for road maintenance would have welcomed the available labour (11). So it seems probable that the workhouse was constructed soon after the Appleby enclosures (1772) which had impoverished so many; and its location chosen where useful work was always available.

The local cottage textile industry, initiated by Joseph Wilkes, was still active in Appleby in the early 19th century as the presence of calico weavers in the Table above shows. As the century moved on, the new factories took over and cottage industries decayed, exacerbating the rural unemployment situation (12).

Appleby Workhouse was in use until 1836 when, following the Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834, Union Workhouses, serving large groups of parishes, were built. The work-for-support principle established in 1723 was applied even more harshly and the many of the poor were removed far from their homes. The Ashby Union Workhouse which served 28 parishes took over the role of the Appleby Workhouse (13). A later map shows that the Appleby building had been demolished by 1838 (14). No trace of it survives today.

Consequences

Arthur Young, the chief proponent of agricultural improvement in the latter half of the 18th century, saw the old method of farming, with its scattered arable strips and common wastes, as highly inefficient and ripe for change. Improvement of agricultural practices would produce the food required for a growing population. Encouraged by Young, larger landowners throughout the country pursued the enclosure of farm land; and agriculture was completely reorganised into a more profitable concern.

Any claim of altruism on the part of the landowners however is surely misplaced. Those who reorganised local agricultural practices by enclosing the land were responding to what we now term ‘market forces’. They saw an opportunity and took it, an opportunity to increase their own wealth. The old subsistence agriculture gave way to profitable enterprise.

The positive consequence of enclosure was indeed to make agriculture more efficient and more food was produced for the increasing population of the country. In fact the rising population was to satisfy the labour demands of the new mills and workshops of industry.

But there was a negative consequence which had been quite unforeseen. Arthur Young lived to see the results of the enclosures and, in 1801, had the good grace to admit that by nineteen out of twenty Enclosure Bills the poor are injured and most grossly (15). Small subsistence farmers were squeezed out for the profitability of newly enlarged farms. At Appleby, the response to the resulting poverty was to construct the workhouse where the poor, removed from their homes, had to work for their keep - almost certainly on the roads.

Charities

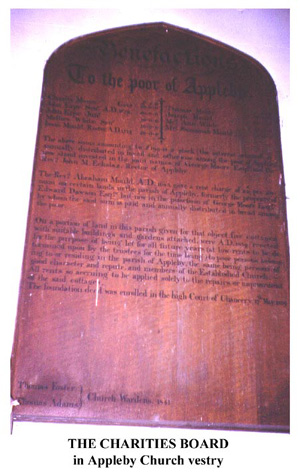

The picture of poverty in Appleby would not be complete without reference to charities set up to alleviate the hardships of the poor of the parish. These are recorded on the Charities Board still displayed on the wall of the Rector’s vestry in Appleby Church, the details of which are reproduced in the Appendix.

From as early as 1679, sums of money were bequeathed to the parish to be invested so that the annual interest could be ‘distributed in bread or otherwise among the poor of Appleby’. By 1841, the date of the board, the total capital amounted to £199‑15s‑2d. In addition to this a rent charge of 25 shillings from certain lands in the parish was bequeathed by Revd Abraham Mould, rector, in 1683. This rent was also used to buy bread for the poor.

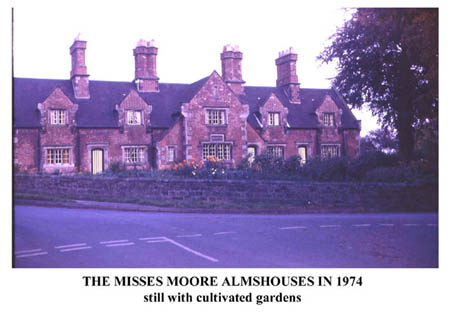

Also recorded on the board is the (then) recent erection of the Almshouses by the gift of the Misses Moore of the White House:

... five cottages with suitable buildings and gardens attached were AD 1839 erected for the purpose of being let for all future years (at low rents to be determined upon by the trustees for the time being) to poor persons belonging to or residing in the parish of Appleby, the same being persons of good character and repair, and members of the Established Church.

It seems most probable that this particular act of charity was prompted by the closure of the Appleby Workhouse and the removal of its residents to the Union Workhouse, several miles away at Ashby, in 1836 as mentioned above.

Notes and References

1. From The Mores [moors] by John Clare (1793-1864)

2. Some of Clare’s poems lamenting the desecration of the old countryside may be found on line at http://www2.phreak.co.uk/tlio/history/clare.html Although not everyone will agree with the opinions on land ownership to be found on this web-site, Clare’s poems speak for themselves.

3. Appleby Magna Parish Registers, Leicestershire Record Office, Ref. 15 D55/44

4. W E Tate, The Parish Chest, CUP / Phillimore, 1983, p 48. The duty imposed on register entries was to pay for the war against France (1689-97) in which Louis XIV was intent on reversing the English ‘Glorious Revolution’ by reinstating James II and his successors. The implementation of the tax appears to have been delayed somewhat in Appleby as the Act of Parliament was passed in 1694 and repealed in 1705.

The Crown (William III) was granted initially for a period of five years a levy of two shillings per birth (significantly not per baptism), 2s 6d per marriage and 4s per burial. Exemptions were made for the poor; and the landed gentry paid at a higher rate on a sliding scale.

The Appleby registers for September and October 1698 include three entries giving the amount of King’s Duty paid and occupations are given presumably to justify the level of tax paid. For subsequent entries up to January 1701, with two exceptions, each entry is marked ‘not worth £50 in land nor £600 in money’ or ‘ ... £600 in personal estate’. The exceptions are local gentry, Charles Moore ‘gentleman’ whose tax is discreetly unmentioned; and George Moore ‘yeoman’ who was ‘worth £50 in land nor [ie and not] £600 in money’. The category of ‘poor man’ also occurs signifying tax exemption.

5. W E Tate, op cit, p 50 Only poor people were identified in the registers between 1783 and 1794, because under the Stamp Act of 1783, duty was imposed at a flat-rate - of 3d per entry. Occupations as such were therefore irrelevant.

6. Implementation of George Rose’s Act of 1812.

7. Appleby Enclosure Act 1771 and Enclosure Award 1772, Leicestershire Record Office

8. Although the 1812 Act required the father’s trade or profession to be stated, it was not required to state that he was actually in work, so the registers do not record paupers at this time.

9. John Clare, from To a Fallen Elm (c.1821)

10. Map of the Parish of Great and Little Appleby in the Counties of Leicester and Derby, 1832 and Reference 1831, scale 8 in:1 mile (in the possession of Sir John Moore School Trustees).

11. William Albert, The Turnpike Road System in England, Cambridge University Press, 1972, pp 201-223, Appendix B ‘The Turnpike Acts 1663-1836’ includes 33 Geo. II (1760) Tamworth to Ashby.

12. D Wright A Survey of the Industrial and Commercial Activities of Joseph Wilkes in and around the Parish of Measham in the late 18th Century, unpublished thesis, Nottingham University, 1968, pp 24-27. Calico weaving shops for 62 hand-looms were built in Appleby parish by Joseph Wilkes around 1790, out of a total of almost 300 looms at sites in Appleby, Ashby and Measham. Wright obtained this information from the Hastings Donnington Papers at the Leicestershire Record Office Ref. DE 41/1/129. Although Wilkes died in 1805, weaving must have continued until 1819 when the shops were put up for sale.

13. K Hillier, The Book of Ashby-de-la-Zouch, Barracuda Books, 1984. The Ashby Union Workhouse was constructed in 1836 as an enlargement of the former House of Industry. The latter was built in 1826 to accommodate about 100 persons from the town.

14. Map of the Parish of Appleby Magna, 1838, with acknowledgement to Mr Charles Ward

15. G M Trevellyan, British History in the 19th Century and After, Longmans, 1948, pp 144-148: a detailed account of the reasons for and consequences of the enclosures and the often ill-judged measures taken to alleviate poverty.

©Richard Dunmore, March 2003

APPENDIX

Appleby Church Charity Board 1841

Benefactions

To the Poor of Appleby

|

£ |

s |

d |

|

|

£ |

s |

d |

Charles Moore Gave |

10 |

0 |

0 |

|

|

|

|

|

John Erpe Senr A.D. 1679 |

20 |

0 |

0 |

|

Thomas Moore |

10 |

0 |

0 |

John Erpe Junr |

10 |

0 |

0 |

|

Joseph Mould |

20 |

0 |

0 |

Mathew White Senr |

10 |

0 |

0 |

|

Mrs Ann Wilde |

10 |

0 |

0 |

Isaac Mould Rector A.D. 1714 |

20 |

0 |

0 |

|

Mrs Susannah Mould |

10 |

0 |

0 |

The above sums amounting to £199 - 15s - 2d stock (the interest whereof is annually distributed in bread and otherwise among the poor of Appleby) now stand invested in the joint names of George Moore Esqr. and the Revd. John M Echalaz, Rector of Appleby.

The Revd. Abraham Mould, AD 1683 gave a rent charge of 25s per annum on certain lands in the parish of Appleby, formerly the property of Edward Dawson Esqr. but now in the possession of George Moore Esqr. by whom the said sum is paid annually distributed in bread among the poor.

On a portion of land in this parish given for that object, five cottages with suitable buildings and gardens attached were AD 1839 erected for the purpose of being let for all future years (at low rents to be determined upon by the trustees for the time being) to poor persons belonging to or residing in the parish of Appleby, the same being persons of good character and repair, and members of the Established Church. All rents so accruing to be applied solely to the repairs or improvement of the said cottages.

The foundation deed was enrolled in the high Court of Chancery 17th May 1839.

Thomas Foster )

Thomas Adams ) Church Wardens 1841

Previous article < Appleby's History In Focus > Next article