Appleby History > In Focus > 4 - Danes, Domesday & a Bequest

Chapter 4

Danes, Domesday and a Bequest

by Richard Dunmore

The Danish Invasions and Settlement

The arrival of Scandinavian invaders in the second half of the ninth century caused widespread havoc throughout northern England (1). By the AD 870s the Danish army was occupying Mercia and it spent the winter of 873-74 at Repton, the headquarters of the Mercian kings. The events are recorded in detail in the Peterborough manuscript of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles (2). After the initial period of devastation, at harvest time in 877 the Danes and the puppet King Ceolwulf, described a 'a foolish king's thegn', divided Mercia between them and the invading army settled peaceably in the area (3). Only forty years later, the Danes submitted to Aethelflaed, ‘Lady of the Mercians’ and sister of the Anglo-Saxon King Edward the Elder, after she took Derby by force in 917 and peacefully obtained the submission of Leicester in 918 (4). However, in that 40 years northern England was subjected to the Danelaw with its punitive tax, the Danegeld, and the administrative structures of the country were indelibly altered. Jurisdiction was centred on military bases at Derby, Leicester, Lincoln, Nottingham and Stamford, the so-called ‘five boroughs’, which after 917 became the foundation for the subsequent Saxon shires, Derbyshire, Leicestershire, etc. Although the Danes held power for only 40 years, a strong, even subversive, Danish element remained in the population for many years to come. Very little archaeological evidence of them survives locally - the remains at Repton are exceptional (5) - but their influence upon place-names was lasting.

Appleby is a hybrid name. The usual derivation quoted is from the combination of 'aeppel' meaning apple tree (Old English) and 'by', farmstead or village (Old Scandinavian) (6). We can deduce from this that Appleby as a settlement already existed at the time of the Danish incursion. There may already have been an Anglo-Saxon settlement, perhaps 'Appleton', whose name the Danes modified. It has been suggested that whether a place remained a 'tun' (village, OE) or became a 'by' depended on the relative number of Anglo-Saxons and Danes in the area. The implication for Appleby is that Danes were sufficiently numerous for their name to supplant the Anglo-Saxon one (7). Recently an alternative derivation has been proposed, based on the premise that the three English villages called Appleby were British until the Scandinavians arrived. All three 'grew up around streams and are not all in places for apple orchards'. The derivation suggested is a combination of 'apa', water or stream, and 'by(r)', settlement and implies that the original settlement pre-dates the Anglo-Saxons (8). A Scandinavian influence may also be detected among the field names of the parish. Although many fields have relatively modern names, some clearly have elements which reach back to the time of Danish incursion and control. This will be discussed further below.

The Domesday Book AD 1086 (9)

There are three entries for Appleby in the Domesday Book, two in the Leicestershire folios and one in the Derbyshire ones. The relevant Leicestershire land holders under the King, known as 'Tenants in Chief', were the Countess Godiva of Coventry and Henry de Ferrers, although the countess, as a Saxon, had been dispossessed (10). That manor had been hers up to the Norman Conquest of 1066. Under Derbyshire, Appleby's third manor is listed under the lands of the Abbey of Burton:

Leicestershire Folios [ff. 231v. & 233v.]

THE LAND OF COUNTESS GODIVA

The countess herself held 3 carucates of land in Aplebi. There is land for 3 ploughs. In demesne are 2 ploughs and 8 villeins with 6 bordars have 2 ploughs. It was and is worth 20 shillings [i.e. both before 1066 and in 1086].

THE LAND OF HENRY DE FERRERS

The same [Robert de Ferrers] holds of Henry 1 carucate of land in Apleberie. There 4 sokemen have 2 ploughs and 3 acres of meadow. It was worth 12 pence [before 1066]; now [1086] 10 shillings.

Derbyshire Folios [f. 273]

M THE LAND OF THE ABBEY OF BURTON

In Apleby the Abbot of Burton had 5 carucates of land for geld. [There is] land for 5 ploughs. Of this land Abbot Leofric leased 1 carucate of land to the Countess Gode [Godiva] which the king now has. In the same vill now in demesne are 2 ploughs and [there are] 8 villeins and 1 bordar with 1 plough. At the time of King Edward [before 1066] the land was worth 20 shillings, now [in 1086] 60 shillings. |

Note: The symbol v following the folio number denotes 'verso', the reverse side of the folio page. The symbol 'M' in the margin, used throughout the Derbyshire Domesday folios, signifies 'manor'. One carucate was nominally 120 acres.

The Domesday Enquiry Process

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle relates how the Domesday Book came to be written.

'Then at midwinter [1085] the king was at Gloucester with his council, and held his court there for 5 days.... After this the king had great thought and very deep conversation with his council about this land, how it was occupied, and with which men. Then he sent his men over all England into every shire and had them ascertain how many hundreds of hides [land area] there were in the shire, or what land and livestock the king himself had in the land, or what dues he ought to have in 12 months from the shire. Also he had it recorded how much land his archbishops had, and his diocesan bishops, and his abbots and his earls, and ... what or how much each man had who was occupying land here in England, in land or in livestock, and how much money it was worth. He had it investigated so very narrowly that there was not one single hide, not one yard of land, not even (it is shameful to tell - but it seemed no shame to him to do it) one ox, not one cow, not one pig was left out, that was not set down in his record. And all the records were brought to him afterwards.' (11)

By this means King William set about regularising titles to land, many estates having been exchanged unlawfully at the Conquest, but above all establishing a value of all the land for taxation purposes. Because the book became the final authoritative register of rightful possession of property under the king, it became known as Domesday Book, by analogy with the Day of Judgement.

The process by which the Domesday material was collected was carefully managed. The basic information was gathered in each manor by reeves, priests and trusted villeins and collated at the hundred and shire courts. The collected answers to the enquiry were presented under oath at a special session of the shire court to the King's Commissioners who toured 'circuits' or groups of shires collecting the material. Surprisingly, despite Leicester and Derby both being part of the Danish 'Five Boroughs' of the north Midlands, the two counties answered in different circuits. The manorial evidence validated by the commissioners at these courts was then assembled into feudal order, that is into quires of parchment leaves applicable to each tenant-in-chief. To avoid any conflict of interest, tenants-in-chief from one circuit sat as commissioners in other circuits. (12).

The manors of the Countess Godiva answered to the circuit Commissioners enquiry at Leicester. She held only three manors in the county: Norton juxta Twycross, Aplebi (Appleby Magna south) and Bilstone.

The manors of Robert de Ferrers, held as a tenant of his father Henry de Ferrers, which also answered at Leicester, were: Netherseal and Overseal, Boothorpe and Apleberie (Appleby Parva).

The manors of Burton Abbey answered at Derby to a different set of Commissioners, because Derby was in a different circuit. These Burton Abbey manors were: Mickleover, Apleby (Appleby Magna north), Winshill, Coton in the Elms, Stapenhill, Caldwell and Ticknall.

Wulfric Spot's Will (13)

The name 'aeppel byg' is given in the will of Wulfic Spot of AD 1004, i.e. in the late Anglo-Saxon period and some 80 years before Domesday. The will was instrumental in founding the new Benedictine Abbey at Burton and Wulfric Spot bequeathed (with many other estates) ‘that land at æppel byg that I bought with my money’. This Anglo-Scandinavian name is the first known written reference to Appleby.

The Anglo-Danish hybrid name must have been used by the vendor of the land to Wulfric Spot and perpetuated by him in his will. The earlier change from a fully Anglo-Saxon name such as 'Appleton' would typify the influence of the 9th century Danish settlers on Anglo-Saxon names as described by Bourne (7). The subsequent change to its Domesday form, 'Apleby', represents a final relatively minor adjustment.

Wulfric Spot's bequest is therefore the origin of Burton Abbey’s Domesday estate at Apleby. The decision at Domesday to include this land in Derbyshire, as one of Burton Abbey's Derbyshire manors, resulted in the division of the village of Appleby Magna between the counties of Leicester and Derby for the next 800 years (14).

It is clear from later descriptions of the Abbey's land that it was a complementary 'half' to that of the Countess Godiva, separated by an unseen line winding through the settlement of the original manor. This tortuous route was to form the basis of the county boundary line between Derbyshire and Leicestershire through the village (15). The evidence points to the northern half of the Appleby Magna settlement being purchased by Wulfric Spot. This point was not understood by the writer of the commentary on the Alecto edition of the Leicestershire and Derbyshire Domesday maps (Thorn), who incorrectly grouped the two Leicestershire manors - of Countess Godiva and Henry de Ferrers - together as Appleby Parva; and considered the Derbyshire manor of Burton Abbey alone to be Appleby Magna (16).

The generic place-name endings 'bi', or 'by', and 'berie' are generally regarded as the usual variation of word forms produced by Norman attempts to spell English place-names. The implication of this view is that not much should be read into such variations found at Domesday. However, their juxtaposition in the three Appleby Domesday returns suggests a real variation in local usage between Appleby Parva on the one hand and the two Appleby Magna manors on the other. There was clearly a difference in perception of the name by the manor officials answering in two separate county courts. The two Leicestershire manors answering at the same Domesday court might be expected to have answered under closely similar names, but they did not do so. The twin manors at Appleby Magna, of Burton Abbey and Countess Godiva, retained the name developed after the Danish settlement with the ending 'bi' or 'by'. In 1086, Appleby Parva was under new, French speaking, management and 'Apleberie' must have been their version of the name. Hence the name they used in answering the Domesday Enquiry.

Villeins and Sokemen

W G Hoskins in his pioneering work 'The Midland Peasant' (1957) discussed what he termed ‘double vills’ and compared their populations and property as described in Domesday Book (17). Although there are in fact three entries for Appleby (see above), the complex settlement appears to fit into the double vill category, recognised later as Appleby Magna and Appleby Parva. Despite dual ownership during over 500 years of Burton Abbey's involvement, Appleby Magna appears always to have been regarded as a single village. It had a structural unity deriving from its pre-Abbey origins.

According to Hoskins' twin village model, one vill (manor) was inhabited by villeins and bordars, who had little freedom and were bound to work their lord’s land in order to subsist on their own meagre plots. The other vill was occupied by relatively few sokemen, who had more land, were relatively free and with more ploughs and ox-teams to work the land, they were also economically and socially superior. The Appleby example is complicated by the possession of half of Appleby Magna by Burton Abbey, but the two Appleby Magna 'halves' do appear to have been economically similar to each other and quite different from the vill of the four rent-paying sokemen at Appleby Parva. The workforce is looked at in more detail in Chapter 8, where the Burton Abbey estate at Appleby is discussed: about 30 years after Domesday, some of the peasants on the Burton Abbey estate were rent-payers with similar economic standing to these Appleby Parva sokemen.

Hoskins had an ethnic explanation for these differences. He thought that the sokemen were the descendants of the Danish settlers, whereas the villeins and bordars were of old English stock, still bound in the Anglo-Saxon feudal system. In the case of the sokemen at Appleby Parva, the 'soke ' or jurisdiction to which they belonged was uncertain.

Polyfocal Village

In the 50 or so years since Hoskins work, in analysing the origins and early development of villages, historians no longer emphasise the ethnic make-up of the population. Instead they recognise the sub-divided lordship of settlements detectable in the so-called 'polyfocal' nature of the settlement (18) (19). A pioneer in this work, Christopher Taylor, proposed that the development of many nuclear villages may have come about, not by simple growth from a single farmstead, but rather from a number of such small settlements which merged into the later village. This multiple structure was termed 'polyfocal'. With his students, Taylor set about identifying the 'focuses' in villages of the East Midlands.

Can this approach help us to understand more subtly than Hoskins' approach the development of the Applebys, Magna and Parva? We must first observe that the Danish arrival was a major event in the development of the village settlement which not only upset the occupation of the land but even influenced the very name of the place. It was relatively late (9th century) so the concept of polyfocal growth would apply foremost to the development of the Anglo-Saxon village before the Danes arrived. The scatter of surviving Scandinavian elements in field names would show how the Danes then fitted into, or took over, an existing developing Anglo-Saxon village.

Danish Field Names (20) (21)

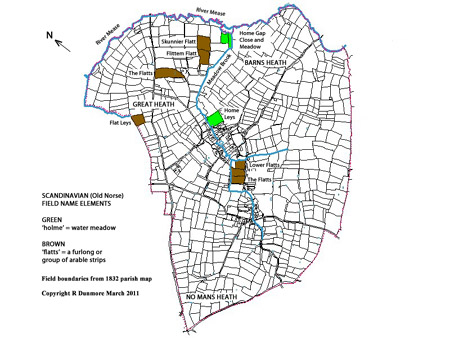

The distribution of Scandinavian name elements may be seen on the following map.

The Scandinavian names occur generally along the shallow valley of the Meadow Brook which flows down through the modern village and joins the River Mease below Barns Heath farm. The meadows were closest to the brook and are identified by the word element 'holme' (water-meadow or riverside land) which has corrupted over the years to 'home'. Arable farming, on somewhat higher ground more suitable for ploughing, is identified by the word 'flatts'. This was a block of arable strips or 'londs' otherwise known as a 'furlong'. It would more accurately have been described as a 'square furlong' ie 220 yds x 220 yds (200 m x 200 m). Technically the area of the furlong was ten acres comprising ten strips 22 yds x 220 yds. In practice, the term was used to describe any large block of londs. In the lower part of the valley the arable workings were on the slopes above the meadows, below the higher ground of the 'Great Heath'. This was the gorsy uncultivated land on the top of what is now called 'Birds Hill'.

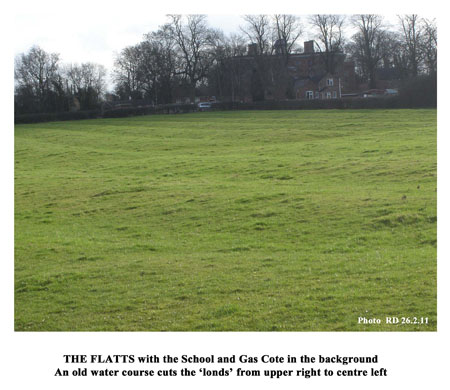

'Flat Leys' on the western side of the heath has the name element 'leys'. This refers to the later practice of convertible husbandry, a system of alternating arable and meadow, with several years of each in turn, to improve and maintain fertility. This particular plot must have started as arable land and later have been adapted to convertible practice. Conversely 'Home Leys', at the bottom of the village, seems to have started as meadow before being adapted to a similar system. At the other end of the village is the field called the 'Flatts', well known to those who walk that way to school. It has a splendid array of londs now 'fossilised' in the pasture (see photo).

The names Skunnier (or Skimmer) and Flittem (also Flitten, Flitton or fflitholme) are also probably Scandinavian. The latter appear to derive from 'flit' and 'holme', a combination of 'brook' and 'meadow'. Indeed, in the 1638 glebe terrier, the open field in this area was called the Meadowbrook Field (22). In this terrier the name appears several times as 'fflitholme leys' (ff was a handwritten equivalent of capital F), in one case with the further expansion 'lyinge next the meadowbrooke'. Another possible meaning of 'flit' is 'disputed'. So 'flitholme' could mean 'disputed meadow' and thus reflect the area's origins in disputed ownership (23).

The idea of dispute may also be present in the name 'Homegap' applied to a meadow and a close at the point of confluence of the Meadow Brook with the river Mease. Having rounded the Great Heath hillside following the Mease, the insurgent Danes would have come across a break in the heathland provided by the meadows, where the brook flowing down from the existing settlement reached the Mease. Hence the 'holmegap' meant the meadow 'gap' or 'breach'. It could be interpreted that at this point the insurgent force 'breached' the territory of the occupants using the easy access provided by their meadows. That the Danes were interested in the territory as farmland for settling is clear from the agricultural nature of the words that survive: holme (meadow) and flatts (arable land). The word 'heath' too existed in the Old Norse 'heithr', but since a similar derivation is available from the Old English 'haeth', the most we can say is that the Danes and the Angles shared a familiar-sounding word. Having taken the lower part of the village territory it looks as if the Danes, moving up the valley alongside the brook, advanced into and took over the village itself, making it their own by eventually changing its name ending to 'by'.

Appleby Parva

The absence of linguistic evidence for activity at Appleby Parva or in the outer southern parts of the parish generally suggests that the upper parts of the parish were undeveloped. The Domesday Book supports this: between the Conquest and Domesday (1066-1086) the value of the land, which Henry de Ferrers acquired as a supporter of King William, rose tenfold: from twelve pence to ten shillings (see the Ferrers' Domesday entry above). So before 1066 the land was hardly exploited at all. The social differences of Domesday, between the sokemen of Appleby Parva on one hand and the villeins and bordars of the manors of Countess Godiva and Burton Abbey on the other, must therefore be attributed to the input of Henry de Ferrers and his tenant son Robert. It follows that the sokemen were introduced by the Ferrers and the 'soke' to which they were attached was theirs. Land on the Leicestershire side of the village eventually came under their control, exemplified by the name of Barns Heath, a corruption of Baron's Heath, the baron being Robert de Ferrers, who became 1st Earl of Derby in 1139 (24). From the evidence here, Hoskins' deductions about twin settlements, such as the Applebys, in 1086 based on the ethnic differences between Danish sokemen and English villeins and bordars cannot be supported. However there was an ethnic divide at Domesday, that between the French sokemen settled at Appleby Parva since 1066 and the old Anglo-Danish villagers of the two manors at Appleby Magna.

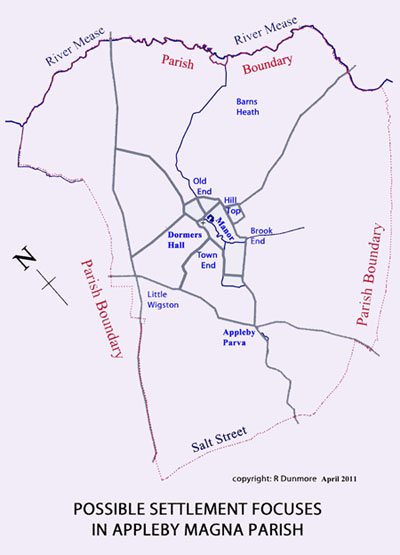

Possible Settlement 'Focuses'

Appleby Magna is a well spread village which makes its origin a promising candidate for Taylor's 'polyfocal' development mentioned above. One of his findings, of possible relevance to us, was the number of villages which had recognisable groups of houses set away from the main focus and referred to as 'ends'. Appleby has a few such 'ends': Old End is well known, but there is also Brook End, off Top Street where the Particular Baptist chapel was built; and the equivalent position along Church Street was probably called Town End, evidenced by the field name 'Far Town End' along Bowleys Lane. So the Appleby 'ends' may have been not just access points to the open fields, but the location of early farmsteads.

As well as the 'ends', there are a number of former farmsteads, often with their buildings surviving, and some older buildings which date back several centuries. Not all of these will have their origins in antiquity but some of them may do. In particular the manor of Appleby Magna, of which the Moat House is a relic, is known to date back to the 12th century in the ownership of the de Appleby family (25) and, earlier still, at Domesday was in the possession of the Countess Godiva. Across the valley to the east, on Top Street, there is cluster of old houses: Hill House, Walker's Hall and Eastgate House with the (until recently) neighbouring Hall Yard farm. On the map which follows I have marked this area as 'Hill Top'. Nearer to Old End at the bottom of Black Horse Hill was Home Leys farm with its neighbour Duck Lake Farm and half way down Top Street lay Jordan's farm (these are not marked on the map).

On the western side of the village lay Church Street farm, the successor to Dormers Hall, itself having occupied the site of Burton Abbey's Domesday land-holding (26). North of the church was the parsonage with its farm buildings which would have its origin in the early development of church property in the 12th/ 13th centuries.

Of the outer-lying settlement focuses Appleby Parva, still sometimes referred to as 'the Overtown', may be traced back to the Ferrers' Domesday land as noted above. Barns Heath farm to the east also owes its name to the Ferrers, being earlier known as Barons Heath, as noted above. To the west Little Wigston lies near the junction of the old turnpike roads close to the oldest known farming site, the Romano-British farmstead (27).

Any of these 'focuses' could have had an early origin which became amalgamated into the developing village. The layout of the streets linking many of these focuses shows evidence of planning and this will be considered in the next article.

Sources and Notes

1. Victoria County History of Leicestershire, II, 1954 (1969 reprint), p 76 (Scandinavian incursion)

2. M Swanton, trans. & ed., The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles E874 [AD 873], Phoenix, 2000, p.73

3. ibid. A877, p.74

4. ibid. C917 Derby, p.101; C918 Leicester, p.105

5. M Biddle, Repton, Current Archaeology 100, June 1986 (Viking finds at Repton, extraordinarily including coins dated 873/74)

6. J Field, English Field Names; A Dictionary, David and Charles, 1972, p 267, Appendix 1, Glossary of Denominatives (name elements)

7. J Bourne, Place Names of Leicestershire and Rutland, Leicestershire County Council Libraries and Information Service, 1981, p 15

8. C Rigg, 'Nailstone revisited', LAHS Newsletter 81, Spring 2010, p.12; see also Chap. 3, n. 11

9. Domesday Book, 1086, Folios 230- 237, Leicestershire and Folios 272 - 278, Derbyshire: facsimile copies and translations, Alecto Editions: Derbys. 1988 and Leics. 1990; facsimiles and translations by Philimore: Derbys. 1978, Leics. 1979, Warwicks. 1976; and the Philimore companion guide by R Welldon Finn, 1973

10.The Burton Abbey Domesday entry referring to land leased to Godiva adds 'which the King now has'; more specifically in the note at end of Godiva's Warwickshire manors: 'Nicholas holds these lands of Countess Godiva for the King's revenue.' Warwickshire Folios 239v.

11. M Swanton op.cit. E1085, p.216

12. H R Loyn, General Introduction to Domesday Book, Alecto Editions, 1987, 3-7

13. Will of Wulfric Spot, 1004, Staffordshire Record Office

14. F R Thorn, ‘Hundreds and Wapentakes’ in The Leicestershire Domesday, op cit, p 29 (Burton Abbey land in Derbyshire)

15. See Chaps. 5 and 8

16. Domesday Maps, Derbyshire & Leicestershire, F R Thorn et al, Alecto Edition 1990, Box 2 : Quote: "The land-unit of Appleby was ... divided between Derbyshire and Leicestershire in 1086, Appleby Magna (Apleby, SK 3109; f.273) being in Derbyshire and Appleby Parva (Aplebi, Apleberie, SK 3008; ff 231v, 233v) being in Leicestershire." This is not correct. The writer was clearly unaware of Wulfric Spot's will and was writing without consideration of the evidence on the ground for the relative disposition of the three Domesday manors. In reality, Godiva's manor Aplebi was the Leicestershire 'half' of Appleby Magna alongside Burton Abbey's Derbyshire 'half', Apleby, at SK 3109. Appleby Parva (Apleberie) was a distinct settlement in Leicestershire.

17. W G Hoskins, The Midland Peasant, Macmillan, 1957, & reprint Phillimore 2008, pp 8-10

18. C Dyer, review of Hoskins 2008 reprint, TLAHS, 83, 2009, 231

19. C Taylor rejected the idea that Anglo-Saxon settlers lived in villages and contended that villages arose in the later Anglo-Saxon-Scandinavian period by merger of small farms or settlements, the 'focuses'.

20. Bosworth School Appleby Estate Survey, 1785, LLRRO, DE633/49

21. Map of the Parish of Great and Little Appleby, 1832 and Reference 1831, School Trustees

22. See Chap. 9

23. J Bourne, op.cit. p.24

24. J. Nichols, History & Antiquities of Leicestershire, IV, part 2, 1811, p.439 (Appleby Parva); and C15 terrier p.438 (Baronsheyth)

25. J Nichols, op.cit., p.426 (Appleby Magna manor); p.431 (Moat House)

26. See Chap. 11

27. see Chap. 2

© Richard Dunmore, November 2000, revised April 2011

Previous article < Appleby's History In Focus > Next article