Appleby History > In Focus > 5 - A Planned Villlage

Chapter 5

A Planned Village

by Richard Dunmore

When Wulfric Spot endowed Burton Abbey in AD 1004 with ‘that land at Appleby that I bought with my money’ there were far reaching consequences for the village and its surroundings (1) (2). From the historian’s point of view, vital clues were given about the origins of the village.

The Derbyshire Boundary

Before 1897, the north-western half of Appleby Magna and several complete parishes to the north-west were in a detached part of Derbyshire, surrounded to the south, east and north by parishes in Leicestershire. This appears to have come about as a result of the ‘detached’ parishes being part of Derbyshire estates at the time that the counties were formed. In the early 10th century Chilcote, Measham and Willesley were part of the royal Derbyshire estate of Repton; and Stretton en le Field had early connections with Repton too. Furthermore, as a consequence of Wulfric Spot's will, the north-western half of Appleby Magna was detached from its south-eastern half and became part of the greater estate of Burton Abbey. By the time of the Domesday survey (AD 1086), as Burton Abbey was not a land-holder in Leicestershire, it was administratively convenient to link the Appleby manor acquired from Wulfric Spot's will, with the Abbey's Derbyshire holdings (3). The authoritative nature of the survey report - the 'Domesday Book' - thus legalised the division of the parish land unit between the two counties, a state of affairs which was to continue for centuries to come.

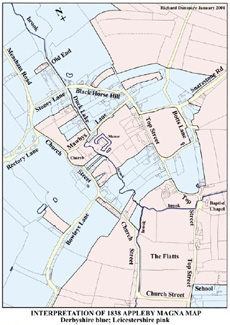

This division of Appleby between Leicestershire and Derbyshire persisted from Domesday until 1897, when the recently created county councils (1889) simplified the administration of many villages in this area by a radical realignment of the boundary (4). The earliest known large scale map of Appleby parish showing the boundary in detail is dated 1838 (5). This shows the parish as it must have stood invisibly divided down the centuries in amazing complexity (see illustrations below). During the 19th century much of this complexity was missed by the Ordnance Survey map-makers, but the 6‑inch OS map of 1887 does show a tortuous, if simplified, boundary line through the village (6). The 1-inch map of 1835 hints at county boundary 'islands' but the small scale prevents resolution of detail (7). The 19th century census enumerators, with two circuits to cover the respective county halves, clearly had difficulties. They simplified their tasks by dividing the parish up in a different way for their own convenience, but this was a recipe for error (8). Unreported errors are detectable in the detailed returns elsewhere (9).

In 1897, as part of a wholesale revision of the boundary to remove the anomaly of the detached part of Derbyshire, Appleby (Derbyshire) became part of Leicestershire as the parish of Appleby North, but still distinct from Appleby South. Incredibly, this still perpetuated the 800 year old division, revealed in the Domesday survey of AD 1086, between the Abbot of Burton's Apleby (Appleby Magna north) and Countess Godiva's Aplebi (Appleby Magna south) - see Chapter 4.

This unnecessary separation (each still had to have its own parish council!) was eliminated the following year with the reunion of the whole parish now to be known as Appleby Magna (10). That the original boundary complexity still existed right to the end is made clear by the 1901 census enumerator's notes. These spell out in detail the streets and properties belonging to the two parliamentary divisions which matched the former county halves (11).

Click images for larger views |

When Wulfric Spot made his land purchase at Appleby Magna, a simple division of the estate might have been expected and on the whole this does appear to have been the case. Across the heath and outlying farmland of the parish the dividing line was indeed straight forward. From No Mans Heath, the boundary headed directly to the heart of the village picking up a drainage line behind the present-day Recreational Ground and aiming for the brook just downstream of Wren Close. On the north-eastern side of the village the boundary followed the edge of the meadow land running alongside the Meadow brook as it flowed away towards the river Mease. The land north-west of Appleby Magna village was acquired by Burton Abbey and became Derbyshire, whilst that to the south-east remained with its Saxon owner and became part of Leicestershire when the shires were formally delineated in the 11th century. Appleby Parva as a separate estate also became part of Leicestershire (12). The emergence of the shires from the territory of the Five Boroughs is thought to have occurred in the 11th century following the accession to the throne of King Cnut (Canute) in AD 1017 (13).

But when it came to defining where the line ran through Appleby Magna village, there were many subtle deviations from a direct course as the 1838 map shows. The complexity of the situation was such that, not only did the line take a tortuous route around individual plots, but several ‘islands’ of each county lay isolated within the other. How and, more importantly, when did this complexity come about?

Is it possible that the original division really was quite simple and that the complexity of the boundary was acquired at a later date? It is difficult to see how this could have happened. The 1772 Enclosure Award confirmed ‘ancient’ enclosures and exchanges of land that had taken place at unspecified times in the past (14). It seems improbable that such enclosures and exchanges could have made the county boundary linemore complex, as that would require the presumption that county designation rested with the allegiance of the owner rather than with thelocation of the parcel of land. This may have been true when the boundary was first delineated, but it hardly seems probable once the boundary had been defined. The ownership of one half of the village by Burton Abbey, with its records kept meticulously by the monks, may also be seen as providing powerful resistance to change, whether unauthorised or demanded by the lord of the other half. Indeed it may be argued that the Abbey's presence was the reason that the boundary complexity survived, at least until the demise of religious houses in the 16th century. After that, the details of boundary became irrelevant to village agriculture as the continuing development of the open field system demonstrates (15).

I have suggested previously that Countess Godiva (d. 1067) would have inherited her Leicestershire lands from her husband Earl Leofric, who died in 1057 (16) (17). Earlier Leofric would have inherited the estates from his father Leofwine on his death in 1023. The authority of the 'ealdorman' or ruler of the province of Mercia was clearly recognised by the conquering King Cnut who assumed overall power in England in 1017 (18). Leofwine was made Earl of Mercia by Cnut, Leofric succeeding his father in 1023. In AD 1004 therefore the land at Appleby which Wulfric Spot bequeathed to Burton Abbey was almost certainly bought from Leofwine. The patronage of religious houses demonstrated the patrons' piety and prestige and the willingness of Leofwine to provide land for Wulfric Spot to endow the Abbey may be seen in that light (19).

The 1838 map demonstrates that through Wulfric Spot's gift, Burton Abbey acquired much of the centre of the village. However, certain key areas were retained by the Anglo-Saxon vendor, Leofwine. These were principally the manor and its surrounding land; the Church and churchyard; and the parsonage land on the north side of Mawbys lane. The manor, the Church and its parsonage would have been central to the old Appleby Magna estate before it was divided for the sale. This reasoning points to the existence of a manorial church in Anglo-Saxon times. These areas appear on the divided map as a large irregular 'island' of Leicestershire (pink) surrounded by a 'sea' of Derbyshire (blue). There are also smaller Leicestershire 'islands' apparently outlining crofts perhaps with individual cottages housing the crofters. Some 80 years later, at Domesday, Godiva's estate employed 14 men some of whom would have occupied these plots, brought to light on the map by the continuing division of the village. They lie against village lanes and some of them (especially near Black Horse Hill) show the distinct curve associated with cultivation strips.

There are also one or two small Derbyshire islands which formed part of Wulfric Spot's purchase. We may surmise that they had been occupied by some of the men tied by service to the land which the Abbey had newly acquired. At Domesday the Abbey was recorded as having 9 men. Each villein’s or bordar’s land went with that of his lord and master, whether that was the original Anglo-Saxon landlord or the new owner, Burton Abbey. What the convoluted line on the map appears to be showing is the location of some of these peasants’ cottages and crofts according to the allegiance of their lord at that time.

It is remarkable that these plots can still be identified today through property boundaries. One of the crofts associated with the Leicestershire manor stands out as an isolated rectangular plot on the north side of Bowleys Lane. This plot of land is notable today as a sunken field, the depressed level arising from the extraction of brick clay in the 19th century. Whether this clay resource was recognised in the 11th century is not known but, if so, this could provide an explanation for the plot being retained by the lord of the Leicestershire manor.

The Planned Village

Trevor Rowley has discussed the views of historians on the age of planned villages, i.e. those whose streets and plots of land were laid out in a methodical way (20). Many believe that these came into being as late as the 13th century, largely on the basis of absence of archaeological evidence of Saxon activity. Other historians maintain that growth of population in the late Saxon period (from AD 750 onwards) led to increased pressure on land use which resulted in two related effects: the reorganisation of agricultural methods by the introduction of common fields; and the concentration of housing in one place - the ‘nuclear village’ - which often shows a planned layout. By these two developments all the resources of the estate would be more easily controlled for the benefit of the community. These resources were, on the one hand, the land communally organised as meadow, pastoral and arable land, common and woodland, and on the other hand, the workforce, now grouped together in the village (nuclear) rather than scattered about in dispersed farmsteads and cottages.

This seems to be what happened at Appleby Magna, a village which shows clear signs of planning (consult the interpretation map above). The map reveals the extent of this planning, but also suggests that earlier features may have been incorporated into the plan. There are two streets roughly parallel to the brook and lying either side of the shallow valley through which it flows. These streets, Top Street and Church Street (using their modern names), are linked by two cross-routes: Mawbys Lane and Stoney Lane/Blackhorse Hill. The Hall Yard footpath, running from Top Street to the Crown Inn just south of the manor and church should also be included with these. At the southern end of the area, the old footpath from Brook End to Town End (now running through Didcot Way and Wren Close via the footbridge) completes a rectangular area. The three 'Ends' marking the limits of the planned area were among possible 'focuses' for early settlement identified in Chapter 4.

Property boundaries shown on the map follow groups of land strips running across the village at right angles to the brook and the main streets. Blackhorse Hill cuts the corner of an otherwise rectangular layout of streets: this is apparent from the boundaries of the plots of land outside its diagonal line to the north. From the point at which Black Horse Hill veers down the hill a lane, accompanied by field boundaries and fragmented lengths of the county boundary, continues the line of Top Street northwards, thus 'squaring' the planned rectangular area stretching from Brook End and Town End in the south to Old End in the north. (This apparently incomplete northern extension of Top Street, with a parallel incomplete northerly development of Botts Lane, could indicate unfinished or abandoned plans.) The diagonal route of Black Horse Hill would have been dictated by the steep gradient of the land and have pre-dated the planning. A path between the suggested settlements at Old End and Brook End, via the Hill Top settlement, must have existed before the property boundaries were delineated. It is noticeable too that Mawbys Lane, also connected to the settlement at Hill Top, is not quite parallel to the strips of land. This is explained if, along with the adjacent land of the nearby manorial home farm, it too existed before the strips were established. Another case, which I shall look at in the next article, is the detour of Church Street around the Church, suggesting that the churchyard was also in place before the village grid was laid out.

The county boundary division of the parish was determined (albeit inadvertently) by Wulfric Spot’s legacy to Burton Abbey. The line shows that a planned village must already have been laid out. The streets were already in place and the village was surrounded by cultivated fields. Detailed examination of the map shows small plots of land cut off by the boundary line and known later to be occupied by cottages, as for example on the south side of Mawbys Lane. Also evident are larger plots, many of them showing the characteristic curved elongated shapes of strips associated with open field arable cultivation, apparently grouped together in piecemeal enclosures. This is particularly evident from the course of the boundary east of Black Horse Hill, where it passed to and fro around or alongside these enclosures. All of these shaped enclosures appear to have been in existence when the property boundaries were defined.

In many instances, the county boundary line followed or changed direction at the village streets. This applied to Black Horse Hill, Bowleys Lane, Church Street, Duck Lake, Mawbys Lane, Top Street, Snarestone Road and Botts Lane and must indicate that the village streets too were already in place at the time the boundary was defined by Burton Abbey's ownership. Many of the streets occupy hollow lanes, with high banks on either side, further evidence of their great antiquity. Stoney Lane and Black Horse Hill are obvious examples but not the only ones. These hollowed ways must have come about by centuries of erosion. The feet of people and animals, the wheels of carts and carriages as well as the effect of water draining to the brook must all have contributed to the relentless erosion of the surface. These streets were therefore already in place when the village was divided between the shires following Burton Abbey's acquisition of the land.

So the county boundary, by following the lines of roads and the boundaries of fields, reveals the antiquity of the village streets and the layout of fields: it pre-dated the acquisition of half of the village by Burton Abbey in AD 1004. But who was responsible for this earlier planning? The Danish newcomers of the late 9th century are the obvious candidates for adapting the village to their own requirements following their settlement. Their arrival in the parish would have put increased pressure on land use, necessitating communal working of the land and the accompanying concentration of housing in the nuclear village (21).

Magna and Parva

As noted above, the planned village at Appleby Magna developed in the shallow valley of the village brook, extending from Old End in the north to Brook End and Town End in the south with the manor farm and church located near the centre. To the north of Old End lay the village meadow land, later improved by controlled drainage of the flood plain. To the south, the path between Brook End and Town End marks the point where the two major streams draining the southern part of the parish converge (near the footbridge at the rear of Wren Close) to form the village brook (which acquires its name the 'Meadow brook' as it flows out across the meadow land to the north of the village). The layout of the land to the south of Brook End and Town End is quite different from that to the north, with the two streets changing direction there by roughly 30 degrees and leading towards Appleby Parva. The Scandinavian origin of the name given to the enclosure fields here, 'The Flatts', may give a linguistic link to the Danish period. The ridged land surface, familiar from medieval 'ridge and furrow' working, also suggests ancient usage (22). The boundary line round a Derbyshire ‘island’ followed the line of Top Street near the (later) school, so at the time the boundary was defined the street must have existed there as a route from the Brook End settlement to Appleby Parva.

However, Appleby Parva was occupied by the Moores, landowners at Appleby Parva manor from around 1600, and they were intent on improving the land. So the change of direction of the southern development may indicate a second phase of planning in the early 17th century.

Slade and Wade

One of the features of the parish before agricultural improvement was natural drainage through a number of slades. These were shallow valleys or green ditches through which, in wet weather, water drained towards the village brook from the surrounding hillside. A surviving 15th century Terrier refers to Oldhillslade, Rowlowslade, Rytheslade, Rushton- or Rushyslade, and simply 'the slade', all draining from the south-western hills. The two streams converging near Wren Close are the result of replacing these old slades by the modern artificial drainage system for the enclosure fields. Agricultural improvement of the land resulted in the physical loss of the old slades, although some may still be detectable as shallow features on the land surface. In the north-eastern part of the parish there were at least two other slades draining water from the Great Heath directly down to the Meadow brook. One of these, detectable on the ground and visible from the air as a green strip (see Google maps aerial view), is at the northern end of the village. The 300ft contour line, shown on the OS 1: 25000 map, displays a V-shaped diversion to the NW. On the southern side of this slade, the modern field name is Wade Bank. Wade is a reference to woad grown from early times for its blue dye, so *Wade Bank* was where woad was grown (see Chap. 33 Field Names sheet 10, field No. 403). The closeness of a slade in the field and a ford on Heath Way (Measham Road) which would require wading in times of flood (23) appears to be a coincidence.

The ridges on the Flatts are crossed by an old drainage line, maybe the remnant of a former slade, visible as a break in the continuity of the ridges and predating modern drainage and realignment of the roads. Support for this observation comes from the Bosworth School Estate Map of 1785 which marks the beginning of a 'foot road' setting off from the corner of Church Street, near the present Wren Close, diagonally across The Flatts towards the 'old road' through the grounds of Appleby Hall. This route, running parallel to the earlier drainage line mentioned, must have predated the present rectangular layout of Church Street (24).

Why and when were these changes of alignment to the drainage routes and roads in this area made? The answer must be agricultural improvement which required better drainage and layout of closes. And the changes must represent a second stage of planning, by the land-improving Moores. So the date of the road layout around the Flatts may be no older than their arrival at Appleby Parva i.e. AD 1600. The name however may hark back much further, to the Danish period.

Just as there was meadow land alongside the brook north of Old End, there was a similar area of meadow at the southern end of the village, also improved by drainage: south of the southern limb of Church Street, names surviving from the 18th century enclosures include 'Kings Meadow' and 'Parkers Meadow' (25).

As noted in Chapter 4, Appleby Parva seems to have had little development before Domesday (AD 1086). The flat land of Appleby Parva was poorly drained and lay at the foot of the southern hills. It seems unlikely that it was cultivated by the Saxons or Danes but, after the Norman Conquest with the arrival of a small Norman workforce under Robert de Ferrers, cultivation began. During the first twenty years of possession by the Ferrers (between the Conquest and the Domesday survey) the value of the land increased tenfold, from twelve pence to ten shillings. There is no obvious evidence of major planning at Appleby Parva at this stage. The small settlement seems to have continued to grow steadily near the old route south from Burton (now A444).

So, the village of Appleby Magna appears to have had its origins in mid-Saxon times, and was subsequently shaped by a large development of village and fields by the incoming Danes in the 9th century. A progressive farming policy appears to have been pursued on their 'half' of the village by the monks of Burton Abbey, until its dissolution in the 16th century. Appleby Parva owes its development to a small group of Normans, who came with William the Conqueror. It was one of the Domesday estates of Henry de Ferrers, the land being probably leased to small farmers, until it was purchased by the Moores at the end of the 16th century. In the 18th century the Moores adopted modern improving methods including enclosure of fields (closes), the realigning of roads and the building of suitably grand houses. New Road, laid out in the 1830s, kept the populace away from the newly established Appleby Hall; it is evidence of far-ranging changes in land use and layout adopted by the Moores at that time. An example of the forward-looking approach to agricultural practices is George Moore (1778-1827), who was awarded a gold medal in 1794 from the Society of Arts for pioneering work in drainage and irrigation (see Chapter 13).

Sources and Notes

Nichols = J. Nichols, History & Antiquities of Leicestershire, Vol. IV, part 2, 1811

VCH = Victoria County History of Leicestershire

LRO = Leicestershire Record Office

1. Will of Wulfric Spot, AD 1004, Staffordshire Record Office (formerly in Burton Library)

2. Denis Stuart, An Illustrated History of Burton upon Trent to the 18th Century, Burton upon Trent Civic Society, post 1993 (pp 3,5 Wulfric Spot and his Will)

3. F R Thorn, ‘Hundreds and Wapentakes’ in The Leicestershire Domesday, Alecto Editions, 1990, pp 28-29 (the attachment of part of Appleby to Derbyshire)

4. Kelly’s Derbyshire Directory, 1895, p 12 (creation of County Councils)

5. Map of the Parish of Appleby Magna, 1838 (showing the complex county boundary line). Grateful thanks to the late Mr Charles Ward for allowing access to the map.

6. 6-inch [1:10560] OS Map 1st Edition, Derbyshire (Det.) Sheet LXIII & Leics. Sheet XXII 1887 (showing apparently simplified boundary).

7. 1-inch OS Map 1st Edition (c 1835) suggests some of the detached Derbyshire islands but lacks detail because of the small scale.

8. 1841 Census returns for the two halves of Appleby show that a simplified division of labour was used. In his return, each enumerator marked those properties which were strictly in the other county. The errors made in 1821 were discovered and reported in 1831 (VCH III, 1955, p 204).

9. 1851 Census returns for Appleby show further apparent changes to the boundary. A sequence of properties in Church Street, listed in 1841 as being in Derbyshire, was recorded in 1851 under Leicestershire. Other properties in Over Street (Top Street), strictly in Leicestershire, were listed in Derbyshire. However, it is doubtful if these confusions produced any significant error in the overall population totals.

10. VCH Leics III, 1955, p 180 (the stages of the union of the separate parishes)

11. 1901 Census Return describes the Boundary of the Enumeration District as 'The Civil Parish of Appleby Magna (entire)'. The Contents of the Enumeration District are then detailed in two sections matching the two parliamentary divisions between which the parish was still divided: 'Western or Bosworth Division (Part of) of Leicestershire' and 'Southern Division of Derbyshire (Part of)'. See the Appendix to Chapter 19, the Appleby Census of 1841.

12. Michael Swanton (trans. & ed.), The Anglo Saxon Chronicles, Phoenix, 2000; first mention of the shires: Derbyshire AD 1048 (p.167); Leicestershire AD 1088 (p.223), although the inclusion of Leicestershire in the Domesday survey is an earlier reference (AD 1086).

13. Charles Phythian-Adams, in The Norman Conquest of Leicestershire and Rutland, Leics Museums 1986, p.9-11, discusses the shiring of the Five Borough territories following the end of the boroughs' confederation at King Cnut's accession.

14. Appleby Enclosure Award 1772, LRO 15D55/44; see also Nichols op.cit. pp. 430-1. The meaning of 'ancient' in this context may simply mean already existing from beyond living memory.

15. See: Chapter 10, especially the Dingle Field

16. Chapter 3, see the Countess Godiva's land

17. Swanton op.cit. p. 292 Family of Leofric and Godiva of Mercia (dates)

18. In the four provinces (earldoms) established by Cnut of Wessex, East Anglia, Mercia and Northumberland, only in Mercia did Englishmen (Leofwine and his son Leofric) retain power throughout this period; Leofwine who was made Earl of Mercia by Cnut had earlier been ealdorman of the Hwicce under Aethelred II, Frank Stenton, Anglo-Saxon England, pp.415-6.

19. John Hunt, Piety, Prestige or Politics? The House of Leofric and the Foundation of Coventry Priory, in Coventry's First Cathedral, ed. George Demidowicz

20. Trevor Rowley, Villages in the Landscape, Alan Sutton, 1987, Chap 4: ‘The Villages of Anglo-Saxon England’

21. Rowley, op.cit. p.103: 'It is possible that the Scandinavian incursions provided a catalyst which stimulated the creation of nuclear villages in northern Britain.'

22. As I noted in the last article, the word flatt is Old Norse for furlong or sub-division of an arable open field (itself divided into strips). This was nominally an area of ten acres, ie one eighth of a mile square. The more common linear measure of the furlong, one eighth of a mile, is familiar to horse-racing punters.

23. Slades are mentioned again in Chapters 6 and 10. The example described here is at SK 317 106. A similar detour of the 300ft contour around the entrance to Parkfield Crescent indicates another old drainage line from the allotment area down through Stoney Lane to the brook at Old End.

24. The 1785 Bosworth School Estate Map (LRO DE 633/49). The line of the old water course across the Flatts can be seen in the photograph of the field in Chapter 4. It reappears as a line of water in wet weather.

25. Another old water course is detectable in the field south of the southern limb of Church Street. This ran from the old north entrance to Appleby Hall across the field opposite to join the drainage route flowing past the Charter House. This line separated Kings Meadow (nearer Church Street) from Parkers Meadow.

©Richard Dunmore, January 2001; revised November 2011

Previous article < Appleby's History In Focus > Next article