Appleby History > In Focus > 7 - Church & Manor Part 2

Chapter 7

The Origins of Church and Manor

Part 2

by Richard Dunmore

Appleby Magna Manor

A 'manor' must be distinguished from the ideas of parish and township. The parish was essentially an ecclesiastical land area associated with and surrounding a parish church. Historically this often derived from the territory of a Saxon ‘multiple estate’ or, as seems likely for Appleby, from part of one (see Chapter 3). A township (the 'vill' of Domesday Book) contained one or more villages or other settlements and was a secular unit recognised by the Crown for tax assessment purposes.

The manor, by contrast, was the dwelling of the lord where he, the 'lord of the manor', lived. It also contained the lord’s hall where rent was paid by his tenants, tax was collected and justice was administered on behalf of the Crown. Functioning as a court, it would also set and supervise the local regulations relating to agricultural procedures and labour services. The lord administered justice in dealing with local (petty) crime. More serious crime was the business of the shire or county court under a sheriff (shire-reeve, or magistrate) (1).

Land Tenure for Military Service

Land ownership was completely revolutionised by William the Conqueror after the Norman Conquest and the effects of this are seen in the Domesday survey of 1086. From the time of William’s reign, land was held in return for military service within a feudal hierarchical structure under the King.

The lord of the manor held his land by knight service through an intermediate tenant-in-chief. Appleby Magna manor became part of the Honour of Tutbury, through which allegiance and service to the King was directed. The holder of this Honour - the ‘tenant-in-chief’ - was the Earl Ferrers who lived at Tutbury castle, and in return for his land he provided fully mounted and trained knights for the King’s fighting force when required. The knights were his sub-tenants in such manors as that at Appleby. The Honours like that of Tutbury, transcended the old Saxon shire boundaries, although many of the tenants-in-chief were also appointed as county sheriffs, as was William de Ferrers at Derby. The counties and their courts continued to function but the structure of power in Norman England was exercised through the Honours, operating like mini-kingdoms (2).

The de Appleby Family

John Nichols records the first identifiable family to occupy the manor at Appleby Magna and who took their name from the village:

the earliest that occurs of the family which took name from the lordship, is Antekil de Appleby (3).

This had been noted in the Burton Abbey Register in a legal document (in conventional medieval Latin) where Antekil de Appleby acknowledges, before the Abbot’s court, for himself and for his heir Radulphus neglect of certain annual services and customary dues which he owed to the Abbey and which he had agreed with the Abbot, relating to two acres of land amongst those he held in the vill of Appleby. This shows incidentally that the Abbey’s ‘half’ of Appleby Magna was governed by the Abbot of Burton’s court.

Although there is no date given for Antekil, the sequence of extracts from the Burton Register quoted by John Nichols appears to put it in the first half of the 12th century. He goes on to say that a William de Appleby was living there about the year 1166 and adds that later, about 1240,

In Appleby [there is] a quarter part of a knights fee, by which William de Appleby holds [the manor] from the Earl Ferrers. ...[and]... In 1312, John de Hastings the elder died seised [ie having legal possession] of a quarter of a knights fee in Appleby, which was in the tenure of William de Appleby.

Here we are seeing knight service in operation, but just how a quarter of a knights fee was paid is not entirely clear. It may mean that a knight spent three months of the year on active military service. Alternatively, it may represent a quarter payment towards the annual upkeep of a knight. The ‘invincible’ royal army of Norman England consisted of some 4000 expensively equipped and trained mounted knights. Each tenant-in-chief would be expected to supply a body of men from his territory. The payment for the tenancy of a manor, whether in actual service or of funding in lieu, was not a cheap option. Locally, the lord of the manor was a man of relative wealth and power.

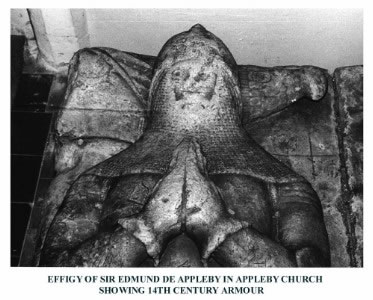

Sir Edmund de Appleby

It is in this light that we can view the military career of Appleby Magna Manor’s most famous tenant, Sir Edmund de Appleby, who held his manor in return for knight service as described above, and whose remains lie in Appleby Church in the de Appleby Chapel, as it was then known. Nichols, quoting the earlier historian William Burton wrote:

Though many of note have descended out of this house yet most eminent was that renowned soldier sir Edmund de Appleby, knt. who served at the battle of Cressy 20 Edw. III. where he took Monsieur Robert du Mailarte, a nobleman of France, prisoner ....

Sir Edmund was clearly one who relished his time in the royal army serving under King Edward III at Crècy in 1346. It is very probable that Sir Edmund died in 1375 (see further comment below).

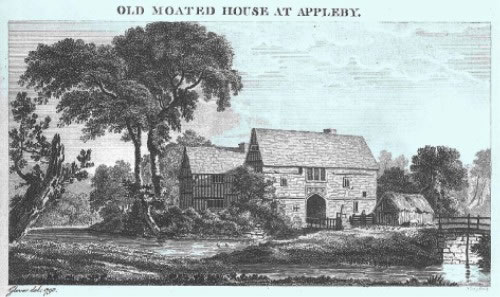

The Manor House

The original manor house and its outbuildings surrounded a courtyard within the protection of the moat. Apart from hidden footings, these buildings have not survived, although the 16th century stone gateway, which forms the frontage of what is now known as the Moat House, must date back to occupation by the later de Applebys (4). Recent evidence from tree-ring dating has added some precision to the dates of the two principal bays of the building (see the fuller account in Chapter 30). Two date periods arising from the tree-ring analysis confirm the visual assessment that the (timber-framed) east bay was built after the stone gatehouse. The construction of the stone gatehouse took place in the first half of the 16th century ie during the reign of Henry VIII (1509-47). The Tudor features of the stonework agree well with this result. The east (timber) bay was added in 1621-22, in the reign of James I (1603-25). A single house was formed by constructing the east bay as an extension (in modern parlance) to the gatehouse, at the same time as modifying the gatehouse itself and thus forming a new composite dwelling. At this point the archway through the gatehouse was abandoned as an entrance to the moated compound.

The Inventory of Sir Edmund de Appleby AD 1375

An inventory of Sir Edmund's belongings was made at this date which, remarkably, has survived almost complete. It is is quoted by Nichols (5). Sir Edmund's whole estate was listed item by item for each room of the house and its buildings. For my translation see Appendix 7.1 (pdf download) (6). The valuations of the items listed are given in either pounds, shillings and pence (l, s, d); or, for some of the more expensive items, in marks (marc'). The value of the mark was 13s 4d (two thirds of a pound) and 6s 8d represents half a mark. If you find the arithmetic confusing, so did those who did the valuations: some of the additions are inaccurate!

Although there are minor errors and omissions in Nichols' text, and some difficulties in translation, the inventory enables us to form a surprisingly clear picture of the manor house interior as it was in 1375. The rooms listed were the Chamber, the Pantry and Buttery, the Hall, the Kitchen and the Larder. Also included are the Bakehouse, the Lord’s Chapel, the Lord’s Stable, the Farm Stable and the contents of the Farm Buildings.

Moat House 1790 (Click image for larger view)

TThe Chamber would have been a large upstairs family room (rather like the large room on the first floor at Donington-le-Heath manor house). The hall beneath was for manor business and furnished accordingly for its use as manor office and court. By contrast the chamber was sumptuously furnished with seven canopied (four-poster) beds, each with hangings in many bright colours: ruby red, blue, black and white. The master bed was of embroidered cloth and ‘half-silvered’. The beds were provided with mattresses, cushions and blankets. Other furniture included storage chests in black, white and sky-blue: the room was full of colour. There were basins and a ewer for washing.

Sir Edmund de Appleby also kept his armour which, in his old age, he no longer used, in the chamber: body armour, helmets and mailed gloves for himself and a saddle sewed together with a ‘tester’ (head covering) and a ‘pisane’ (breast-plate) for his horse. No doubt the children of the house would have asked frequently about his campaign in France with King Edward III. They would have been told of the famous victory at Crècy (1346) and how he took a French nobleman prisoner. An idea of what Sir Edmund looked like in his armour can be obtained from his effigy in the church (see more about Sir Edmund’s Armour below).

The Pantry and Buttery were well equipped with five bowls listed, two of which were ‘silver-gilt with crowns and roses’. A further three were silver. There were also a silver ewer (large water-jug), four mazers (hardwood plates or cups), 15 silver spoons and three tablecloths, three over-tablecloths, three canvas cloths and four towels. There were also 12 barrels, four metal candlesticks; tubs and bottles and ‘leather’ pots.

The Hall, or Court Baron, by comparison, was sparsely furnished, but this was the business room where taxes and rents were collected and which operated as the court chamber where the lord administered justice locally. The farmers came here too each year to agree the programme of rotation and sowing and reaping of the crops. The hall had a large partition and tables and forms as well as two basins and ewers for washing. Importantly at this date, there was a chimney, perhaps portable, to vent the smoke from a central fireplace and an ‘iron fork’ (some sort of poker?).

In the Kitchen, were five dozen pewter vessels and two pewter chargers (plates), bronze pots and pans, and a 'pastonet' - perhaps a pastry board. Then there was the cooking equipment: iron spits, a cob-iron and griddle, a frying pan, hot iron, hooks, a grater, knives for the dresser, and two bronze mortars and pestles.

In the Larder, was a salting trough, 30 baskets, three weights bobus -bobs (as in plumb bobs), a salt-box and a board or working surface. Salt played a vital role in the preservation of food, as well as being used for seasoning.

The Bakehouse would almost certainly have been detached from the main house because of the risk of fire. It contained various vats and moulds used for bread making. There was a kneading trough, a bolting box, which was for ‘bolting’ or sieving flour, and a pail. Many of the vats were made of lead, which was not then known to be toxic.

The Lord’s Chapel contained a complete set of vestments with a chalice, a ‘book’ (probably a missal) and a portable altar or an altar-slab. It has previously been assumed that this chapel was part of the manor buildings. However the Church lay only a short distance west of the Manor House and it had been enlarged, probably by Sir Edmund some 30 years previously. The ‘old chancel’ was retained as the de Appleby’s Chapel, probably serving as a tomb-chamber and chantry chapel where prayers were regularly offered by a chantry priest for the family’s dead, a distinctly medieval preoccupation. It seems likely therefore that the Lord’s Chapel of the inventory refers to the de Appleby Chapel within the church building.

In the Lord’s Stable was a horse for the lord himself, a grey, and three more horses viz. another grey, a dun and a bay.

In the Farm Stable, were five horses for the farm carts, ropes and harness and two iron tires for the cart wheels.

In the Farm Buildings were 12 oxen and nine ploughs: three made completely from iron, four with iron ploughshares, and two with wood. The cattle comprised two bulls, 19 cows, eight two-year-old steers, two one-year-old steers, five calves and another six oxen ‘for the plough’. Nichols’ transcript of the document has gaps in this section (presumably it was illegible), but there were 88 of something else - probably sheep.

The total value of the inventory was put at £260-7s-10d. The most expensive item of furnishing in the chamber was the master bed at £5-6s-8d. The armour however at almost £15 was worth more than 40% of the total contents of the chamber (£35 12s). In the pantry the two silver gilt and two silver bowls were together valued at £7-6s-8d. The vestments etc in the chapel were put at £5. The lord’s grey horse was also worth £5, as were his other three horses valued together. The five cart-horses were worth £6-13s-4d. The 12 oxen were valued at £10, the two bulls and 19 cows £13-6s-8d, and all the steers, heifers and calves £3-16s-4d.

Sir Edmund & Lady Joan in the 'De Appleby’ Chapel (click for larger view)

Sir Edmund’s Armour

The alabaster effigies of Sir Edmund de Appleby and his Lady in the de Appleby Chapel in Appleby Church show them in period garments; in particular Sir Edmund is depicted in armour. James Thompson gives a more complete description of Sir Edmund’s armour (and the Lady’s dress) which adds to the information given in the inventory (7):

The gentleman wears a conical helmet or bascinet, to which a camail, or mail tippet [a head piece hanging to the shoulder], is attached. His body is invested in a jupon [sleeveless jacket], and the mail armour is shown in the gussets at the elbow and armpits, and beneath the edge of the jupon. The legs are cased in cuisses and greaves [upper and lower leg armour], and the girdle encircles the hips, though the dagger has been broken off. The armour is in the style used in the reigns of Edward the Third and Richard the Second, between the years 1350 and 1400. The lady wears the small reticulated and veil head-dress, with a gown plaited close and stiff from the neck.

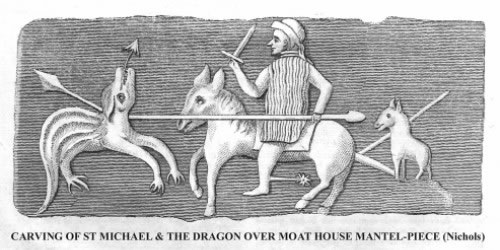

Thompson also comments upon the ‘curious carvings’ to be found over the fireplace in the Moat House, which are illustrated in Nichols (8). In particular there is a representation of St Michael slaying a ‘dragon’. What has caught Thompson’s eye is that the spur on the heel of St Michael ‘is unquestionably a copy of one in use when the carver executed his quaint sketch. It is the long spiked rowel of the reigns of Henry the Fifth and Henry the Sixth (from AD 1413 to 1461). To this period we may also assign the front of the house; while the building [bay] at the rear is, perhaps a century and a half older’. I cannot comment on the accuracy of these observations, but they are certainly of interest.

After 1375

The inventory of Sir Edmund de Appleby’s belongings made in 1375 is a very strong indication that he had recently died (9). However, Nichols leaves us a puzzle by giving details of his apparent military and diplomatic activity after 1375. Considering Sir Edmund was on active service in France in 1346 and, as the inventory relates, had put his armour to one side as ‘disused’ by the date the inventory was made, it seems unlikely that he would go to France with the youthful John of Gaunt (b. 1340) in 1385 to sue for peace between the two kingdoms; or again the following year with John to ‘Castile’ to claim that kingdom on behalf of John’s wife the lady Constance, co-heir to Peter king of Castile. This is surely referring to a younger man. It seems that Nichols must have overlooked the possibility that there was another Sir Edmund, perhaps son of the first, and that these later events refer to him. Nichols quotes a legal document known as a ‘quitclaim’ dated 1392 in which Edmund de Appleby, knight, renounced all legal actions and claims against John de Curzon of Falde. This must again refer to a second Sir Edmund de Appleby. Be that as it may, the de Appleby family continued to live at the manor for many years to come.

In fact the de Applebys continued to hold the manor at Appleby Magna until the middle of the 16th century. Nichols seems to imply that the Hastings family were in legal possession of the manor in the fifteenth century, but this may have been only part of the Appleby estate:

John Appleby, of Appleby, by a deed dated in 1430, confirmed lands in that lordship to W.H. [probably W. Hastings] On the seal are the arms of Appleby.... In 1436, Richard Hastings, knt. died seised [ie in legal possession] of one messuage and two virgates of land, with the appurtenances, in Appleby ... and Leonard Hastings was his brother and next heir.... In 1455, Richard Duke of York, Henry Grey and four others were ‘seised, on the day when Leonard Hastings, knt. died, of one messuage and two virgates of land at Appleby.

Nichols makes no reference to Hastings in the sixteenth century but reverts to the de Applebys:

Another of the Appleby family, lineally descended from Sir Edmund, was George Appleby, slain in defence of the Isle of Inkippe near Scotland, after Musselborough field, 1 Edw. VI [1547] ..... The last-mentioned George Appleby left two sons; 1. George, who alienated [ie sold] the property at Appleby in 1549, and was afterwards drowned; and 2. Richard; whose only son Francis died s.p. [without issue] in 1630, leaving two sisters, coheirs ...

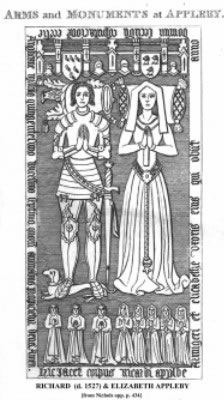

Another Richard, probably the father of George, died in 1527. The splendid carved stone over his tomb in the de Appleby chapel is illustrated by Nichols (and shown below). He is depicted in armour with his wife Elizabeth and their children, five girls and three boys, presumably including George. Unfortunately this stone did not survive the nineteenth century restorations of the church. So the de Appleby occupation of Appleby Magna manor came to an end with the sale of the property in 1549 and the male line ceased with the death of Francis in 1630.

Monument stone formerly in Appleby Church, 1527 (click for larger view)

A Martyr

Nichols, never one to miss an interesting aside, tells us that Joyce (née Curzon) the widow of George Appleby (slain in Scotland in 1547) afterwards married Thomas Lewes of Mancetter, near Atherstone; and that she was burnt at the stake at Coventry in 1557 for her ‘constancy of religion’. In a footnote, quoting John Foxe’s The Acts and Monuments of Martyrs, 1641, Mrs Lewes is described as:

... a gentlewoman born, delicately brought up in the pleasures of the world, having delight in gay apparel, and such like foolishness, with the which follies the most part of gentlefolks were then and are yet affected.

Nichols appears to be in error about the place of her martyrdom. She was burnt at the stake at Lichfield on 18 December 1557. A fellow Mancetter Protestant, Robert Glover, was tried at Lichfield and burnt at Coventry. Their memorials are in Mancetter Church (10).

In the next article, I shall look at the other half of Appleby Magna, the land of Burton Abbey, including the tenants at the beginning of the 12th century.

APPENDIX 7.1 Inventory of Sir Edmund de Appleby's Goods 1375

(pdf download)

Notes and References

1. Charles Phythian-Adams, ‘Lordship and the patterns of estate fragmentation’ in The Norman Conquest of Leicestershire and Rutland, Leicestershire Museums, 1986, pp16-18 (lordship and the manor)

2. Daniel Williams, ‘Domesday Book and the feudal aristocracy of Norman England’ in The Norman Conquest of Leicestershire and Rutland, op. cit. pp 23 (tenure by knight service); p. 24 (Norman 'Honours' such as Tutbury).

3. Nichols op.cit. p 428. The date for Antekil de Appleby is deduced as follows: Folio viiib of the Abbey Register quotes the time of Henry I [1100-35] and Abbot Nigel [1094-1114], ie in the overlapping period between 1100 and 1114; Antekil de Appleby is referred to in folio xxxi; immediately following this, Nichols dates William de Appleby at 1166. Antekil de Appleby appears therefore to have held the manor at a date between 1114 and 1166.

4. The Moat House underwent restoration in the 1960s, aided by a Ministry of Works grant, after being purchased by Mr & Mrs Henry Hall. A dilapidated farmhouse, it had been issued with a ‘closing order’ in June 1960 by Ashby de la Zouch Rural Council and threatened with demolition (Leicester Mercury 26 Oct 1961). The Leicestershire Archaeological & Historical Society were prominent in championing restoration (TLAHS 1960, p x).

5. Nichols op.cit. p 429 (the inventory of Sir Edmund de Appleby - see Appendix 7.1).

6. R E Latham, Revised Medieval Latin Word-List and Supplement, OUP, 1980 (principal word source used)

7. James Thompson, ‘A Medieval Manor House’, The Midlands Historical Collector, Vol.I No.4, November1854, pp 50-57 (Sir Edmund’s armour and Moat House carvings)

8. Nichols op. cit. between pp 430 &431 (Moat House carvings).

9. The deduction that the date of Sir Edmund de Appleby’s inventory (1375) was also the year of his death is not mine alone. It was also the assumption of historians at the Tower of London in 1983. They made use of Sir Edmund’s inventory when working on the reconstruction of a knight’s bedroom for one of the little towers. Information courtesy Mr & Mrs Geoff Frisby. I am also indebted to them for the photographs of the effigies in Appleby Church.

10. Alan Munden, The Coventry Martyrs, Coventry Archives, 1997, p 9, refers to Joyce Lewes’ martyrdom at Lichfield. A modern mosaic memorial to the (at least 13) Coventry Martyrs, including Robert Glover, may be found near the entrance to Broadgate House in Coventry city centre, below the ‘Lady Godiva’ clock. It is illustrated on p.11 of Dr Munden's booklet.

©Richard Dunmore, May 2001: Inventory translation,

reference numbers and minor amendments, October 2013

Previous article < Appleby's History In Focus > Next article