Appleby History > In Focus > 6 - Church & Manor Part 1

Chapter 6

The Origins of Church and Manor

Part 1

by Richard Dunmore

As shown in the last chapter, a planned settlement had been established at Appleby Magna before the arrival of the Danes around AD 900. It straddled the shallow valley occupied by the village brook. The central core of land was occupied by the manor farm, the church and a rectory. This area remained in the Leicestershire half of the village after part of the manor land was sold and bequeathed to Burton Abbey’s Derbyshire estate c. AD 1004.

Valley Setting and Water Courses

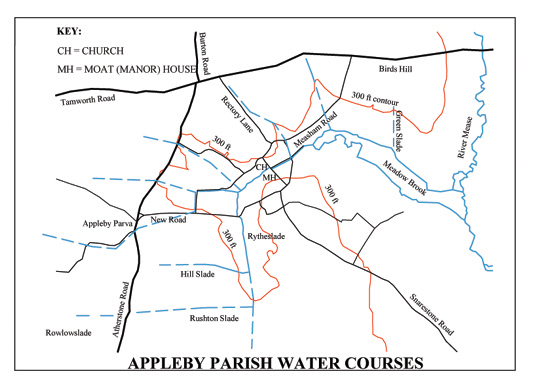

The steepest part of the valley is the point at which drainage water from the higher land to the south-west funnels through a relatively narrow gap before the resulting brook levels out to flow down wide meadows to join the River Mease about a mile away at the boundary with Measham parish. The village is centred on the manor (Moat House) and the church; and the positioning of these two buildings, one each side of the brook at this narrow neck, is no accident. It must be a strong indication that the settlement site was chosen in early times.

The reason why Appleby has occasional floods is clear from the 300 ft contour line, marked in red on the map below. The south-western half of the parish (on the left) acts as a wide irregular shallow basin lying under the surrounding hills. The contour line represents the rim of the basin and drainage water, collecting in it from the hills, pours out through the ‘spout’ between the Moat House and the church.

Map of Parish Water Courses (Click for enlarged pdf version)

Mention was made in Chapter 5 of slades, natural water courses draining to the brook from the surrounding hills and higher ground. Most of these have disappeared as a result of the enclosures when water was directed into drainage ditches along the edges of the new fields (called 'drains' on large-scale OS maps). The position of some of the old slades can still be detected from subtle variations in the topography of the land surface and reveal themselves when heavy rain causes flooding.

Rarely, some slades have survived where little improvement has been made to the pasture of the enclosure. The positions of some of these slade lines are indicated by broken blue lines on the map. Note in particular the line of the 300 ft contour line near the Measham road with its V-shaped diversions around two of these water courses. The most easterly of these can still be seen in the unimproved pasture. Other old water courses may be detected crossing Atherstone Road at Bowleys lane; and another one in line with the Charter House. It is notable that in these places the roads are susceptible to flooding. The names of some of the slades survive in old field names (see map). Green Slade lay just east of the White House, draining directly down to the Meadow Brook. Hill Slade and Rushton Slade, among others, drained the southern hills. Rytheslade drained the area south-east of Top Street, an area known as Roycroft at the time the School was built; the brook which now flows behind the south-western side of Didcott Way is clearly its modern replacement 'drain'.

It seems likely that the site for the manor buildings was chosen because of the abundance of water in the narrow valley. The stream afforded a fresh water supply as well as a means of discharging effluent. With the construction of the moat, it would also provide defence for the house and buildings. It could also have provided power for a mill, although this is not proven, but in any case, that may not have been attempted until a later date. There is an insufficient continuous supply of water to power a mill today, but the climate may have been more suitable (i.e. wetter) for short periods in the past. The altered course of the stream near the moat and under the shop does suggest that practical use of water power was intended. The moat may have doubled as a mill pond fed by a mill stream from higher up the valley. A water-wheel would have been placed at the north-eastern corner of the moat, with used water flowing directly away from the mill wheel down Duck Lake. The present course of the brook (through the Moat House grounds) would have acted as a relief channel for unused water. Even if a mill were successful for a while, failure of the enterprise was inevitable when the weather became drier.

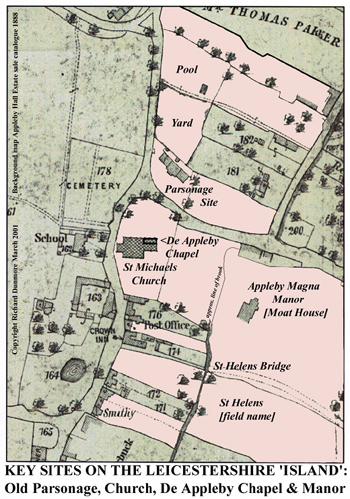

The Heart of the Village

Amongst all the complications of the division of the village between Leicestershire and Derbyshire (described in the last chapter), one large Leicestershire ‘island’ lies at the heart of the village, at the geographical centre by the brook. Bridging the valley, this particular ‘island’ contained the manorial home farm together with the church and its parsonage, despite the fact that the church and parsonage were on the Derbyshire side of the brook. At the time of the land partition in AD 1004, the Anglo-Saxon owners retained the strategic core of the original Leicestershire village estate (see KEY SITES plan, below).

Anglo-Saxon Owners

We know from Domesday Book that Countess Godiva, widow of Leofric the powerful Earl of Mercia, had been the land holder in Appleby and other neighbouring Leicestershire villages in the period immediately before the Norman Conquest of 1066. It appears that Godiva inherited estates from Earl Leofric when he died in 1057 (see Chapter 3, Countess Godiva's land). Before that, Leofric had inherited from his father Leofwine at his death in 1023. Another Leofric, Abbot of Burton, held the northern half of Appleby Magna at the time of the Domesday survey. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles record that Abbot Leofric was Earl Leofric’s nephew. Aelfgar, Earl Leofric’s son and successor as Earl of Mercia (in 1057), married a great-niece of the Mercian nobleman Wulfric Spot, Burton Abbey’s founder, who would have purchased the Appleby northern estate from Leofwine. The picture emerges of a small group of noble families, closely related to the House of Leofric, holding land and power, both secular and religious, in Anglo-Saxon Mercia in the first half of the 11th century (1) (2) (3).

Evidence for an Early Church at Appleby

Although the present church, on the evidence of its fabric and architectural style, dates from the early 14th century (4), it may be deduced from surviving records that a church and parsonage existed well before that. Nichols (1811), drawing on early sources, lists rectors and patrons back to AD 1207 (5). No church building is mentioned as such, but the induction of a rector involves the handing over of the ‘temporalities’ of the parish, meaning all the physical property and revenue required to enable the priest to administer the parish. It is highly probable therefore that a full parochial system was in place at this time, with a church (forerunner of the 14th century building), rectory and glebe; and income from tithes.

An explicit reference to a church at Appleby in a 13th century document backs this up. A lease of land dated 29th September 1262, which has survived in the Hastings Manuscripts, states:

29 September, 1262. - Lease by James, son of Sir Geoffrey de Appilby, to Roger the smith, of half an acre of land in Appleby Parva, lying at the head of the vill and Abutting on “West Wellgrene”; to hold for twenty years from Michaelmas, 1262, paying 6d. and two horse-shoes (ferros equinos) per annum. Witnesses - Sir Thomas Dandeville, rector of the church of Appleby, Henry, son of Sir William de Appilby, Roger and William Pescher, Richard and thomas le Herpor, Matthew son of Gilbert, and others(6).

Whilst this document is of great interest in its own right, the important point here is that Sir Thomas Dandeville was rector of the church of Appleby in 1262 i.e. he had a full parochial appointment with all its privileges and duties. Incidentally, Dandeville fills a gap in Nichols’ list of rectors which is incomplete at this early date. A further point to note is that the parcel of land in question was lying at the head of the vill, i.e. it was at the forefront of development of heath land at Appleby Parva. West Wellgrene would have been an area of quality pasture on the edge of the common (see Chapter 10).

There is one further reference to a church at Appleby which is even earlier. In tracing the history of Appleby Parva manor, Nichols quotes the historian Burton: ‘I find by an old deed, that Robert de Stokport gave this manor, with the advowson of the church of Great Appleby, to William de Vernon and his heirs, about the time of king John’ [i.e. 1199-1216]. The existence of the advowson, or rights of patronage, points to a parochial system supporting a church and rector already operating in the early 13th century (7).

What form did this church take and where exactly was it? Clues lie in the physical appearance of the present church building and its location in the churchyard. The almost uniform architectural style (Decorated Gothic) and design of the bulk of this 14th century building (chancel, nave and side aisles) suggests that it was designed and built in one operation (8). The chapel at the north-east corner of the building appears to be earlier, although, according to Pevsner, no earlier than about 1300 (4). Could this chapel be on the site of the earlier church?

St Helen's Chapel

In the mid-14th century, this chapel became the private chapel of the de Appleby family within an enlarged church. The chapel contained the family tombs and it seems probable that it was rebuilt before the main part of the church. Erected before the Reformation, it would have functioned as a chantry chapel, specifically endowed for chantry priests to offer prayers for the souls of the benefactors.

Such chapels were often built within a larger church, but here at Appleby the chapel seems to have replaced an early, probably Saxon, building; the main part of the later church having been built around it in the 1340s. This deduction comes from the position of the chapel within the churchyard (see below). This major church building work would have taken place on the initiative of Sir Edmund de Appleby i.e. rebuilding the chapel, then building the new church. After he died in 1375, his body was laid to rest, with that of his wife, beneath the alabaster effigies which may still be seen in the chapel (9).

The dedication name of the enlarged church is Michael. An earlier dedication name for the chapel seems to have been conveniently forgotten or abandoned at the Reformation, but remarkably it has survived in local folk memory. South of the manor (Moat House) and within the same Leicestershire ‘island’, there was a field enclosure known as ‘St Helens’. The name also survives for the bridge which carries the Hall Yard footpath over the village brook (see Key Sites map). Dr G R Jones has produced evidence of Michael replacing Helen in some Leicestershire church dedications after the Reformation, Michael being more conformable to Protestant sensibilities (10) (11). This points to the dedication name Helen being associated with an early Saxon church and subsequent chapel up to the Reformation.

Confirmation that the chapel in Appleby church had an early dedication to St Helen has been found in the will of Edmund Appleby made in 1506. The relevant passage of the will translates as 'and my body to be buried in my Chapel of St Helen in Appleby aforesaid with my ancestors'. With so many of the family buried there, there can be no doubt that this chapel is where Edmund was buried and that it was dedicated to St Helen. Edmund Appleby's will is discussed more fully in Chapter 30.

Although the present structure appears to be no earlier than 1300 (4), it is likely to be a replacement for, or rebuild of, the earlier Saxon church of which Sir Thomas Dandeville, amongst others, was rector. It could even contain some of the fabric from an earlier stone building. However, it is more likely that an earlier structure was wooden, particularly if it originated before the arrival of the Danes. There is also the possibility that a wooden church was destroyed during the Danish period and a stone replacement built later, perhaps in Godiva’s time, but there is no evidence for this. Of course, a replaced wooden building would leave little archaeological evidence.

The Churchyard

It was usual for a Saxon church to be sited centrally within a circular burial ground (12). The placing of the new church building off-centre to the west left the older chapel, with its family graves, at the centre of the Saxon site. Church Street, which from about 1004 carried the county boundary line here, takes a curved path around the site. The burial ground, with the small Saxon church at its centre, could accommodate the church enlargement.

In Church

David Parsons has described what a Saxon church would have been like at the time of Domesday (1086). The church ... was a small building capable of holding only two or three dozen people. There were no side aisles, only a small box-like nave with a small chancel to the east ... There were no seats for the public, who would have had to stand throughout the services, though there may have been benches against the wall for the infirm.... The altar was at the east end of the nave or just inside the chancel. In the case of the nave altar, the priest probably stood under the chancel arch and celebrated the mass facing the people. If the altar was just east of the chancel arch, the priest may still have celebrated westward from a position in the middle of the chancel.

He points out that the ‘modern’ idea of the priest celebrating the sacrament facing west and in the midst of the people, rather than facing east at a remote altar (a medieval position), was already foreshadowed at Domesday (13).

The Parsonage

We are familiar with the modern Rectory (1954) and its predecessor, the ‘Old Rectory’, both situated in Rectory Lane some distance from the church. An earlier parsonage was demolished and a new one (the ‘Old Rectory’) built around the turn of the 18th century on land awarded to the rector of the day by the 1772 Enclosure Award. Nichols gives some details:

1807. The old parsonage-house which stood in a field nearly adjoining the church-yard, on the North side, was taken down, and a very excellent new one built, on a new site, a quarter of a mile West from the church, at the sole expence [sic] of the Rev. Thomas Jones, rector .... (14)

The 1606 Glebe Terrier (inventory of church property) pins down the location of the old parsonage more precisely:

The Homestead or Site of the parsonage situate and lying between the Poolyard on the North side and the street on the South side ... Within the said bounds are contained one orchard and one garden containing by estimation 5 poles (15).

The Pool Yard was the name of a garden or small enclosure behind the present Almshouses and alongside the road to Measham and now occupied by part of St Michael’s Drive (see KEY SITES plan) (16). The street referred to must be Mawbys Lane, and the buildings were roughly where the Almshouses now stand. A later glebe terrier (1638) gives a fuller description of the parsonage in the early 17th century:

The dwelling house with that which adjoineth to it containeth five bays of buildings, three of them have plaster flowers over them, the other two are boarded. Also on the east side of the house stands one other piece of building containing three bays, one of them for a kitchen, one other for a kiln and the third for things belonging unto both, two of them having plastered flowers and the third hath none. Also on the west side of the dwelling house stands a barn of seven bays. And also one other piece of building, four little bays used for a stable and a house to set cattle in.

The parsonage was clearly a substantial complex of buildings. A bay is the section of a building between the principal supporting structures. We may suppose that all the buildings were timber framed, with a renewable infill between the subsidiary timbers of either lath and plaster or boards. The plastered flowers were clearly a decorative feature of the plastered gable infills; and evidence of status (17) (18). The reference to barn and cattle house shows that the rectory was a working farm as well as the dwelling of the rector. In this distant outpost of archdeaconry (Leicester) and diocese (Lincoln), the rector would be used to accommodating over-night guests and this is reflected in the size of the house and the stabling. The kiln in the bay next to the kitchen was probably a bread oven. The location of kitchen and kiln in a separate building, detached from the main house, would be a deliberate ploy to reduce fire risk.

It seems likely that the site of the parsonage building, adjacent to the church, is medieval and contemporary with the earliest (12th century) incumbents. The parsonage would at first have been a relatively simple dwelling in keeping with the parson’s simple life. At the time of Domesday (1086) ‘worker-priests’ sharing communal ploughs laboured alongside other villagers in the open fields (13, 19). However, the post-Reformation Mould dynasty who acquired the advowson (living) in 1610 and kept it in the family until 1793 (see In Focus 26), could be expected to have constructed a building more in keeping with their gentry status. It would be their building which was replaced by the even grander 'Old Rectory' c.1800.

In the second part, I shall consider the manor itself.

Notes and References

1. Anglo-Saxon Chronicles, Peterborough manuscript, translated by Michael Swanton, Phoenix Press, 2000 , records the death, in 1066, of Abbot Leofric, Earl Leofric’s nephew. Swanton also gives many useful genealogical tables including the descendants of Wulfrun the Mercian Lady who founded the Minster at Wolverhampton. Wulfric Spot her son founded Burton Abbey. A grand-daughter Aelfgifu married King Cnut (Canute). It was another Aelfgifu, her great grand-daughter (and Wulfric’s niece) who married Aelfgar heir to Earl Leofric and Lady Godiva (the founders of St Mary’s Cathedral and Priory at Coventry).

2. Charles Phythian-Adams, 'Lords and the Land', discusses the pre-Conquest dominance of the powerful House of Leofric, in The Norman Conquest of Leicestershire and Rutland, ed. Phythian-Adams, Leicestershire Museums Art Galleries & Records Service, 1986, pp 18 - 23

3. John Hunt, in ‘Piety, Prestige or Politics’ in Coventry’s First Cathedral ed. Demidowicz, Stamford, 1994, discusses the development of the Earldom of Mercia. Before the Norman Conquest, the key to understanding land tenancy lies with the ambitions of the House of Leofwine, Earl Leofric's father. Leofwine, Ealdorman of the Hwicce, to the south-west of Mercia, had been created first Earl of Mercia in AD 1017 by King Cnut (Canute) in a major reallocation of power. Leofwine, who was succeeded by Leofric about AD 1023, had begun to acquire territory in Mercia as early as AD 998. By the time of Domesday, the family had acquired a large number of manorial estates throughout Mercia. Land tenure was an essential part of lordship, as was the patronage of religious foundations. Although acts of genuine piety were involved in religious patronage, family and political prestige were also being promoted. It seems probable that Leofwine acquired the Appleby ‘multiple estate' soon after AD 998, part being sold to Wulfric Spot for Burton Abbey in 1004 and the rest coming eventually to Godiva after Leofric’s death in AD 1057. Earl Leofric was clearly in a position to influence the appointment of his nephew to Burton Abbey in AD 1051. By 1066, part of Burton’s Appleby estate was sub-tenanted to Godiva, who thus acquired a partial income from Abbey lands.

4. N. Pevsner, The Buildings of England: Leicestershire and Rutland, Penguin 1977, pp 47-48 (date of church and de Appleby Chapel)

5. Nichols, op.cit pp. 434-436 (rectors): his list of 'rectors' begins with Henry Lewel 1207 followed by Richard Middi, 1220, when the patron was Richard son of Roger (p 436). On p 434, he expands on this: 'In the Matriculus of 1220, Appleby is described to be under the patronage of Richard FitzRoger; the rector, Richard Middi, had been instituted by Hugh former bishop of Lincoln.... ' This bishop must have been Hugh of Wells (Bishop of Lincoln 1209-1235) rather than his more famous predecessor Hugh of Avalon - St Hugh of Lincoln - who died in 1200; see also (10).

6. Report on the Manuscripts of the late Reginald Rawdon Hastings of the Manor House Ashby de la Zouch, Historic Manuscripts Commission, HMSO, 1928, p 47 (1262 lease of land)

7. Nichols op. cit., p 439 (Appleby Parva and Church advowson). His reference is to William Burton, Description of Leicestershire, 1622 (2nd edition 1777)

8. The uniformity of the church nave and side aisles is apparent from the geometry of the building betraying the designer’s hand: the rectangular space provided jointly by the nave and side aisles is very close to square; and the width of the chancel arch is double that of the nave arches.

9. Burials of the de Applebys in their chapel are noted by Nichols op. cit. (p 436). It is no longer a chapel but houses the church organ chamber and vestries. Details of Helena and the the adoption of Christianity by her son the Emperor Constantine for the 'Holy Roman Empire' were discussed in Chapter 2 'the Roman Occupation'

10. David Farmer, The Oxford Dictionary of Saints, OUP, 1997 (St Michael, St Helen, St Hugh)

11. Graham Jones, Saints in the Landscape, Tempus, 2007, p. 68: Michael as dedicatee of cemetery chapels; p.69: post-Reformation replacement of Helen by Michael in Leicestershire church dedications.

12. Whitehead, M A, Escomb its Village, People and Churchyard, May 1979: a rare example of a Saxon church, in County Durham, surrounded by its almost circular burial ground, ‘God’s Acre’.

13. David Parsons, ‘Churches and Churchgoing in 1086’ in The Norman Conquest of Leicestershire and Rutland, op. cit. p 42 (conditions in church; and ‘worker-priests’ in the fields)

14. Nichols, op. cit., p 432 (demolition of old parsonage)

15. Appleby Glebe Terriers, 1606, 1638, LRO. I am again grateful to Alan Roberts for his transcriptions of the Glebe Terriers. I have modernised the spelling. The garden size of 5 poles [square poles] amounts to 151 sq. yards or 126 sq. metres.

16. Map of the Parish of Great and Little Appleby in the Counties of Leicester and Derby, 1832 and Reference 1831, scale 8 in : 1 mile, gives the location and field name of Pool Yard (Sir John Moore School Trustees).

17. Eric Mercer, English Vernacular Houses, Royal Commission on Historic Monuments, HMSO, 1979. This gives details of house structures such as timber frames and infill materials such as clay plaster. The infill could be replaced when necessary. The Black Horse Inn has infills of brick, which may have replaced a different original material.

18. For technical information on clay plaster see: www.buildingconservation.com/articles/clayplaster/clayplaster.htm.

19. In Focus 8, The Land of Burton Abbey: The conditions of service of village peasants working with the priest under Burton Abbey's reeve on the Appleby Estate in the early 12th century are described here.

©Richard Dunmore, March 2001; revised April 2012 and April 2013

Previous article < Appleby's History In Focus > Next article